30 of our favourite films directed by women

March 8 is International Womens Day, and there’s no better time to learn more about the bold, iconic, diverse works that women have given cinema.

Here’s just 30 of the many female-directed movies that Flicks writers love the best—with picks courtesy of Rachel Ashby, Amelia Berry, Lillian Crawford, Eliza Janssen, Katie Parker, Amanda Jane Robinson, Fatima Sheriff, Katie Smith-Wong and Sarah Thomson.

Being roughly one half of the population, women are not a monolith; and the same goes for women behind the camera, a fact that’s driven home by the list we arrived at when we asked nine terrific female Flicks contributors for their top ten fave movies from female directors.

Out of 71 films in total, there was absolutely no common thread between these recent must-sees, underseen gems, and stone-cold classics. The top 30 list covers experimental cinema, bubbly rom-coms, searing documentaries, and some of the greatest action and horror films of all time.

Claire Denis emerged as our team’s most loved director, winning three spots in the poll, with Agnès Varda, Chantal Akerman, and Lynne Ramsay close behind with two entries each. There wasn’t even room for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, recently crowned as the highest-grossing film from a woman director ever, to sneak into the top tier. Scroll to learn more about each writer’s connection to this fierce female watchlist, and to find links for where to watch each film.

American Psycho

Dir: Mary Harron | 2000

The 1991 Bret Easton Ellis novel that created homicidal businessman Patrick Bateman is a tough read, with mercilessly sterile sex worker murders sandwiched between page-long descriptions of where Pat got his suit, shirt, pocket square and glasses for each day’s snazzy outfit. It took Mary Harron, and screenwriter Guinevere Turner, to develop the text’s toxic ideas into something iconically chilling—let alone watchable at all. Their eyes are keenly focused on the existential void at the centre of metrosexual, post-Reagan, woman-hating masculinity, finding the horror and undeniable humour in Christian Bale’s “murders and executions” Ken doll. Boardrooms, yuppie apartments, and the most tedious, high-end New York eateries never looked more like abattoirs. ELIZA JANSSEN

Beau Travail

Dir: Claire Denis | 1999

Loosely based on a homoerotic Melville novella, Claire Denis’ macho masterpiece treats the camaraderie, duties, and violence of French Foreign Legion soldiers as a twisted dance. Then there’s the actual dance Denis Lavant whips out in the film’s final scene; one of the best, most energising movie endings of all time.

Bright Star

Dir: Jane Campion | 2009

One of Campion’s more romantic works, capturing the love story of poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw) and Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish) in a period piece that’s largely free of the darkness seen elsewhere in her films.

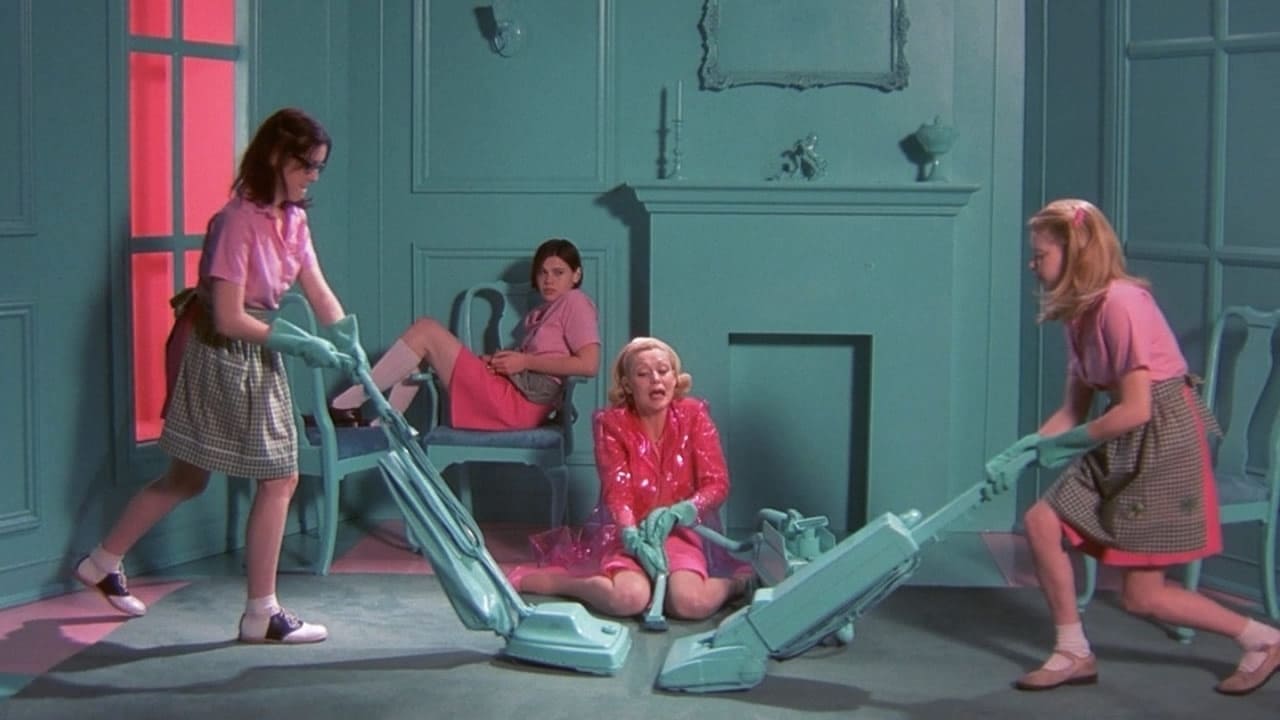

But I’m a Cheerleader

Dir: Jamie Babbit | 2000

There are plenty of mopey dramas about queer conversion programs out there, but this one dares to reach for the pastel-painted heights of pastiche, casting Natasha Lyonne as a reluctant lesbian who discovers herself (and heartthrob Clea Duvall) at a hilariously heteronormative camp. Babbit wrings sweetness out of a bleak, angry scenario; Cathy Moriarty, our fave Melanie Lynskey, and bloody RuPaul co-star.

Chocolat

Dir: Claire Denis | 1988

I’ve been a Claire Denis girl for years now, but had somehow missed seeing Chocolat, her 1988 debut, until its restoration screening at Auckland’s Civic last year as part of the New Zealand International Film Festival. Set in Cameroon during the final years of French rule, the film is drawn from Denis’ own childhood in West Africa as the daughter of a French civil servant. I was taken by its sophistication, Denis’ knack for telling an intricate, complex story with such style and immediacy. Her singular command of the visual, as well as her ongoing narrative interests—memory and desire and the reverberations of French colonialism—are already present here. When I picture it now it’s the texture of the grass, Isaach De Bankolé’s face, the way the light falls. I think of it often. AMANDA JANE ROBINSON

Cléo from 5 to 7

Dir: Agnès Varda | 1962

Widely considered the Mother of the French New Wave for her status as one of the movement’s only female filmmakers, Varda imbued her day-in-the-life jaunt with a looming sense of the ominous. Star Corinne Marchand might look like she’s dining, flirting, singing, and enjoying her breezy routine—but the film’s set on the longest day of the year, and a tragic fortune colours each black-and-white scene with troubling potential.

Clueless

Dir: Amy Heckerling | 1995

Written and directed by Amy Heckerling, Clueless features its own spin on Jane Austen’s Emma and brings it up to date with a fancy wardrobe and its unique dialogue amid the Beverly Hills teen elite. Alicia Silverstone charms audiences as the naive yet sweet-natured Cher, whose self-centred efforts to help others through love and makeovers help her realise her own ‘cluelessness’, realising that looks, popularity and money don’t exactly lead to inner happiness. The film also provided a springboard for future stars Paul Rudd, Donald Faison and the late Brittany Murphy, whose brilliant insult to Cher remains one of the most memorable teen comedy lines of all time. Almost 30 years on, Clueless remains a modern cult film that defined a generation of teenagers before the digital age while showing audiences that classic novels can work as a modern adaptation. KATIE SMITH-WONG

Daisies (Sedmikrásky)

Dir: Věra Chytilová | 1966

Raucous, gorgeous, and running just 70-odd minutes, this Czechoslovakian comedy is a powerful hour of fun with two rebellious chicks, both named Marie. It’ll free any viewer to break the petty rules of their mundane lives, from causing scenes in hoity-toity male spaces to hanging out in a bathtub full of milk, bitching about mortality. Infectious, feminist, fun.

The Gleaners and I

Dir: Agnès Varda | 2000

Throughout the history of art, women have been depended upon as record-keepers; creatives with a particular eye for preserving humanity’s past, even when it seems inconsequential or tedious. Varda makes this task feel exuberant in her first doco of the new millennium, finding glee and sensitive understanding in her portraits of folks turning discarded trash and excess into treasure.

How To Have Sex

Dir: Molly Manning Walker | 2023

You can (and should) check out the most recent entry to our list in cinemas right now; it’s a vital debut film from one of the women revitalising contemporary British film alongside Raine Allen-Miller and Charlotte Wells. Manning Walker told Flicks about the impetus behind the holiday drama, which tracks the sexual trauma of young women holidaying after graduation: “A big thing we realised through this was that teenagers don’t really talk to each other about that stuff. It was also interesting to see that the same old insecurities and pride about sex were still present for this group, even though a lot of stuff in the culture has progressed and moved on.”

Illusions

Dir: Julie Dash | 1982

Set in a not-so-distant Hollywood of 40 years before this film’s release, Julie Dash’s debut feature boldly tackles huge questions of race, representation, and womanhood. Main character Mignon (Lonette McKee) is a Black woman passing for white on her way to studio system stardom. It’s a fascinating speculation on the stories the film industry tells of America, and it reflects inwards to Dash’s groundbreaking position in cinema history too.

India Song

Dir: Marguerite Duras | 1975

An Indian vice-consul—and also we, the audience—are treated to a hypnotic seduction by Delphine Seyrig in an abandoned Rothschild mansion. Marguerite Duras captures every dreamlike layer of her story’s characters and the luscious architecture in which they’re trapped, proving that her direction could be just as evocative and precise as her fiction, memoirs, plays and screenplays.

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

Dir: Chantel Akerman | 1975

Peel potatoes. Turn off the light. Screw a client. Greet your son when he’s back from school. Voted the greatest film of all time in Sight & Sound’s most recent poll of international critics and filmmakers, Akerman’s immense slow-cinema masterpiece alternately stunned and infuriated viewers who were checking it out for the first time. The director herself believed that “women’s cinema does not exist”; if it does, though, her most audacious and restrained work belongs at the throne.

La Ciénaga

Dir: Lucrecia Martel | 2001

From being inspired by gloomy memories of her own family to its consideration as the greatest Argentinian film of all time, Martel’s somber portrait of a bourgeoisie household features breathtaking, naturalistic child acting alongside complex adult performances.

Les rendez-vous d’Anna

Dir: Chantal Akerman | 1978

What sets Les rendez-vous d’Anna apart from Chantal Akerman’s more acclaimed masterpiece Jeanne Dielman is its dynamism. The later film contains all the feminine disquietude of the film that made Akerman’s name, but it transforms it into a semi-autobiographical narrative reflecting on the essential themes of her work and life: motherhood, sex, and filmmaking. Aurore Clément is mesmerising as Akerman’s double, perhaps even more so than Delphine Seyrig, holding the viewer rapt in her cutting, tired glare. Couple that with Akerman’s beautiful signature longshots and it makes for one of the finest films ever made. LILLIAN CRAWFORD

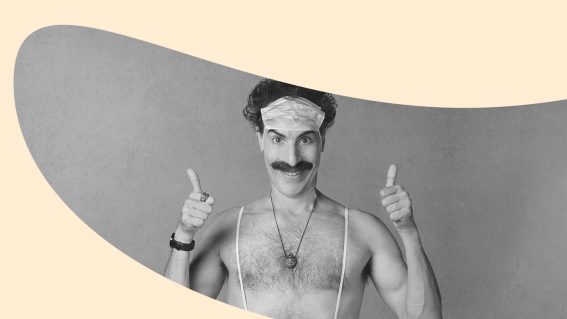

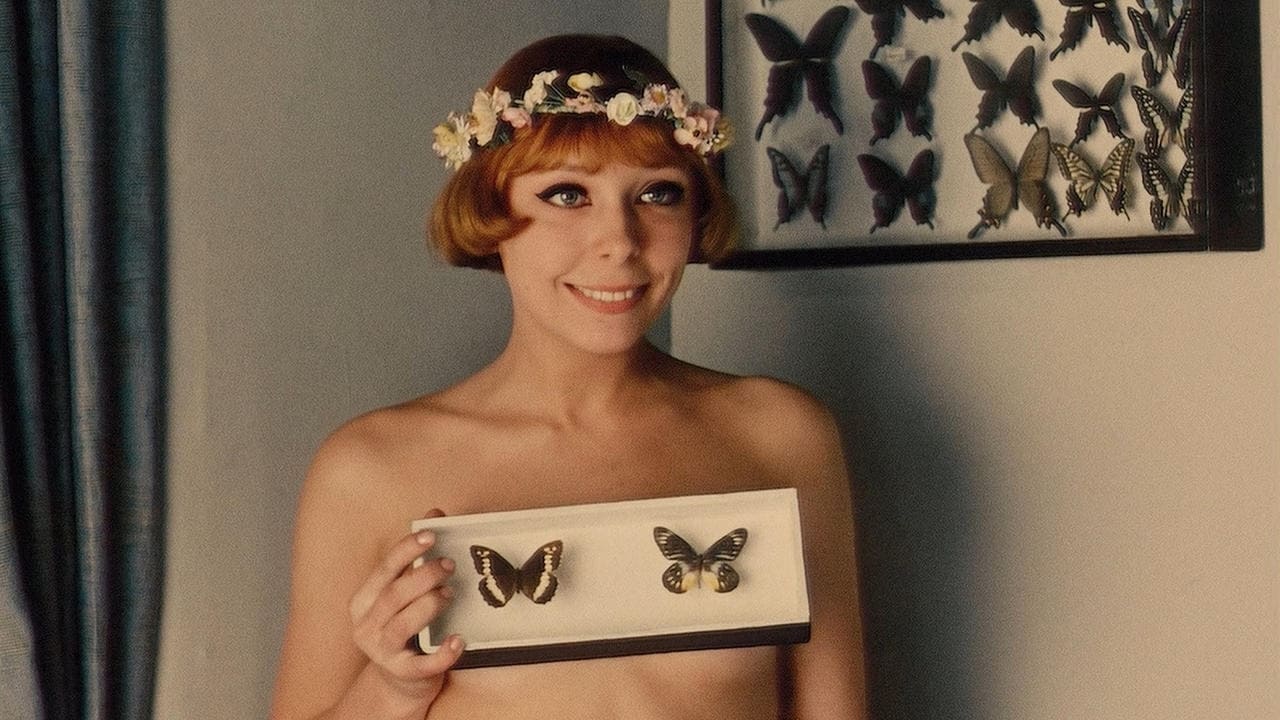

The Love Witch

Dir: Anna Biller | 2016

“Tampons aren’t gross. Women bleed and that’s a beautiful thing. Do you know that most men have never even seen a used tampon?” Set in the present day but kitted out in glorious, psychedelic-era production design, Biller’s supernatural sex comedy has a surprisingly complex conception of femininity. Its mannered hero (Samantha Robinson) is desperate for romance, and is willing to crush useless men in her mystical quest to end up with the right one.

The Matrix

Dir: Lilly Wachowski & Lana Wachowski | 1999

Few films have found themselves as enmeshed in the popular imagination as Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s 1999 sci-fi masterpiece, The Matrix. Its slick blend of Hong Kong martial arts, cyberpunk style, and anime flare, along with some galaxy brain philosophical themes, brought a new kind of artfulness to the world of the Hollywood action blockbuster. “Makes you think” has never looked so cool. AMELIA BERRY

Meshes of the Afternoon

Dir: Maya Deren & Alexander Hammid | 1943

Cyclical and claustrophobic, Meshes of the Afternoon exemplifies both the medium of short film and the genre of surrealism. Deren and Hammid created a work that warps the viewer’s sense of time and space with clever storytelling and camera-work that plays with repetition, shadows, and gravity. This dizzying puzzle box of cinema has stood the test of time, and in a cinematic landscape saturated with CGI, it shows how much atmosphere you can create with a simple set and a handful of iconic props. FATIMA SHERIFF

Morvern Callar

Dir: Lynne Ramsay | 2002

The ultimate “good for her” psychological drama follows Samantha Morton’s listless supermarket worker, as she discovers her boyfriend’s suicide on Christmas morning…and then takes credit for the unpublished novel he’s left behind. The soundtrack is beyond cool, and Lynne Ramsay perfectly captures the free-fall of emotional emptiness; consider it a bleak fantasy of escapism, with all the romance scooped out.

Paris is Burning

Dir: Jennie Livingston | 1991

An essential and eye-opening peek into New York’s ballroom scene of the late 1980s. Through talking heads with the community’s queer legends—confident mothers, wannabes, vogueing pioneers and trans sex workers yearning to find security—the documentary invites all viewers to question what it means “to be real”, assessing the city’s straight world as one big pageant, too.

Patu!

Dir: Merata Mita | 1983

A landmark film in the truest sense, Merata Mita’s Patu! (1983) documents an incendiary time of polarisation in New Zealand’s recent history that still has huge ripples in the country’s present politics and identity. As has often been noted when discussing Mita’s work, her view of contemporary activism blew out of the water any notion of everyday New Zealanders’ disinterestedness in world politics and highlighted a moment when local activism was beginning to make connections with international movements of shared philosophy. Mita’s commitment to being right in the thick of it brings the viewer into the action in a singularly close, and oftentimes claustrophobic, way that encapsulates the intensity of the era—though her staunch depictions of police brutality, racism and the uglier sides of 20th century New Zealand patriotism came at great personal cost. Recommended follow: her son Heperi Mita’s truly moving documentary Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen. RACHEL ASHBY

Peppermint Soda

Dir: Diane Kurys | 1977

Beginning with the title card “For my sister—who still hasn’t given me back my orange sweater”, this coming-of-age classic feels like the kind of film that could only come from a raw, first-time directorial talent. Which is correct here: Kurys was only inspired to pick up a camera when she realised she was tired of stories about teen boys. Its attention to the vulnerable, yearning state of feminine adolescence gave way to plenty of the films on this list, plus Greta Gerwig’s Oscar-nominated Lady Bird.

Strange Days

Dir: Kathryn Bigelow | 1995

Cooler, more experimental, and—yeah—stranger than any of her ex-husband James Cameron’s films, Bigelow’s original sci-fi thriller tackles tough themes of sexual assault and oppression through an inventive tech-noir lens. The opening scenes, of Ralph Fiennes’ POV witnessing his love interest Juliette Lewis rollerskating around Venice Beach, capture the male and female gaze in one fantastical, warped package.

Titane

Dir: Julia Ducournau | 2021

French filmmaker Julia Ducournau’s follow up to her deliciously provocative debut Raw, this neon tinged vision of body horror, mechanophilia, and found family earned her the honour of being just the second female filmmaker to win the Palme d’Or—and the first to win it solo (Jane Campion’s The Piano shared honours in 1993 with Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine). A surreal, grotesque, and yet weirdly poignant story of a pregnant female serial killer posing as a lonely firefighter’s long missing son, Titane takes genre filmmaking to insane new places, guaranteed to elicit strong reactions—and signposts Ducournau as one of modern cinema’s most extreme and exciting voices. KATIE PARKER

Trouble Every Day

Dir: Claire Denis | 2001

A vampiric love story with a rotten heart, Denis’ erotic thriller received scathing reviews upon its release, only to be rescued in the decades since by viewers with dark tastes for horror and existentialism. Blood has never looked so glamorous, so sexually-charged onscreen.

The Virgin Suicides

Dir: Sofia Coppola | 1999

Our highest-ranking choice from one of the most popular female directors alive. It’s a delight to fall for the morbid Lisbon sisters, as the watchful male characters in this adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides novel do. Coppola’s wistful aesthetic decisions—the dreamy soundtrack, costumes, and romanticisation of terrible acts—make the film a beautiful product of its time, laced with 1990s adolescent apocalypse.

Wanda

Dir: Barbara Loden | 1970

Shot on location with an improvisational nature and a seven-person crew, this hurried DIY gem ingeniously toys with our sympathy towards its impulsive title character. Critics of the 1970s found Wanda—the film and the bank-robbing hero—frustrating and pointless, but it’s since been reclaimed as an early, spectacular indie piece, championed by everyone from Isabelle Huppert to John Waters.

Wayne’s World

Dir: Penelope Spheeris | 1992

“Wayne’s World is not the film Penelope Spheeris wants to be remembered for,” cries the LA Times. Well, shit. Hear us out though. Working with (and often against) a rough childhood, Roger Corman, Richard Pryor, Flea—and here, with an SNL-inflated Mike Myers—it’s Spheeris’ knack for nailing the impossible friction of what it is to be human that imbues all their best work. What makes us reject housing and find ourselves in gutter punk—as in Spheeris’ iconic music doco trilogy The Decline of Western Civilization? Reject safety and find ourselves on the margins—as in Spheeris’ Suburbia? Reject Aurora, Illinois and your mom’s basement (bogus and sad) for a dream of something bigger? You can’t truly excel at satire unless it’s done with knowledge and love. And for that, Penelope Spheeris: we salute you. SARAH THOMSON

We’re All Going To The World’s Fair

Dir: Jane Schoenbrun | 2022

We're All Going to the World's Fair

Could this be the first great film about how the internet is melting our brains? Inflected with doom and creepypasta horror, Jane Schoenbrun’s low-budget debut leaves room for bleak questions of coming-of-age, trans identity, and transhumanism, all while making us scared for—and then scared of—its screen-obsessed teen protagonist.

You Were Never Really Here

Dir: Lynne Ramsay | 2017

Much like her earlier entry into our top 30, Lynne Ramsay’s latest thriller follows a lost character through a melancholic, liminal world, soundtracked by sweet and cheery retro-pop. That character is Joaquin Phoenix in one of his many roles as a broken, doomed man, here a mercenary trying to liberate a little girl from a shadowy trafficking operation. Clearly Ramsay can do blockbuster action and violence; she just chooses to employ it in the most unpleasant, stomach-dropping manner possible.