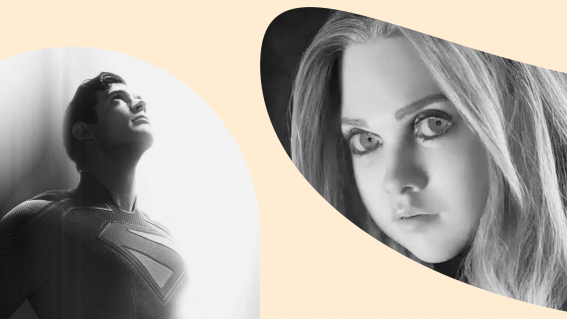

5 unconventional police dramas to watch after The Stranger

Seen That? Watch This is a weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, it’s gloomy cop drama The Stranger, and five of its finest peers that take the genre in different directions.

It doesn’t take long to ascertain that director Thomas M. Wright’s sophomore feature, The Stranger, is a different kind of police drama, ensconced in an atmosphere of gloom so thick you could cut it with a knife. The film begins with drone footage of grey skies, a mist-rimmed mountain and an aerial view of treetops, accompanied by an enigmatic voice-over: “Just put your attention on the breath coming into your body as you inhale,” the narrator says. “It’s clear. Nothing. And as you breathe out, the air that comes out of you is black.”

This man could just as well be talking about the experience of watching the film: if you come to it peppy-chipper, you leave feeling asphyxiated. In other words, The Stranger—which revolves around an undercover operation to identify the murderer of a missing boy—is another happy-go-lucky Australian film to add to the nation’s collection of frothy feel-good fare, including classics such as Animal Kingdom, Snowtown, Chopper, Nitram and Romper Stomper. Stone the crows, mate: Aussie crime movies are fair dinkum.

Stylishly made, with darkly elegant cinematography and editing, The Stranger is a compelling contemplation of trauma—not of the victim’s (which is fairly common in films) but the trauma experienced by Joel Edgerton’s cop Mark, who is deep undercover. While Netflix doesn’t publish viewer data, this unconventional film has clearly connected with audiences—landing in the top 10 in more than 50 countries. Here’s five suggestions of other films to watch for audiences looking for something different from a police drama.

Noise (2007)

A killer is on the loose—and it’s up to Constable Graham McGahan (Brendan Cowell) to stop them. So far, so genre. But two core elements relating to the protagonist push writer/director Matthew Saville’s debut feature in unconventional directions. The first: McGahan suffers from tinnitus, meaning any gunshot will really hurt irrespective of whether the bullet connects. The second: he’s been taken off his usual duties and positioned in a police caravan—situated in a community rocked by a recent shooting massacre—which becomes a kind of quasi-confessional booth, locals arriving and venting about various aspects of their lives.

Instead of the narrative being about cops going out to catch the criminal, the killer comes to McGahan, being one of the visitors to the caravan. Brendan Cowell’s tired, bedraggled performance hits exactly the right notes, and Saville creates brilliantly moody vibes—in part through an ambitiously layered soundscape that convincingly illustrates the pain inside the protagonist’s head.

The Guilty (2018)

Productions like this Danish thriller from Gustav Möller are essentially filmed plays, unfolding through conversations held in a single setting—here an emergency services call center. Protagonist Asger Holm (Jakob Cedergren)—a cop who’s been taken off the beat for reasons gradually revealed—takes a call from an abducted woman (voice of Jessica Dinnage) and pulls various strings to help her, all remotely, with Möller’s cameras never leaving the dispatch desk.

The Guilty is a great example of building tension using an unexpected focus point: the man on the phone rather than the abductee in the car. By not showing the most obviously dramatic things, the director prompts the audience to imagine them for ourselves, much of the action existing in the mind’s eye. The decision to remain around Asger for the entire runtime places a huge emphasis on the central performance; this presumably appealed to Jake Gyllenhaal, who stars in the Hollywood remake of the same name.

Se7en (1995)

David Fincher’s notorious serial killer movie sticks to the soul like mud to a blanket. By now you probably know the big twist (if not, spoilers ahead) in which Kevin Spacey’s serial killer John Doe delivers to Brad Pitt’s Detective David Mills his wife’s head in a box. This entices the hot-headed Mills to murder him—committing the final wrathful act in a series of crimes inspired by the seven deadly sins. Mill’s partner is the more sensible William Somerset (the ever-dignified Morgan Freeman), who is about to retire—a screenwriting convention known as the “one final case before retirement” trope.

But there’s nothing conventional about that classic, soul-destroying ending, which left viewers clutching the walls and renouncing their religions. The fact that many remember seeing the head of Gwyneth Paltrow (who plays Mills’ wife) despite it never being visualised is a great example of film’s power to create images that exist only in our heads.

Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950)

This whiplash-sharp thriller from Otto Preminger—whose other classics include Laura and Anatomy of a Murder—is vintage noir, embodying many of the movement’s best features. It’s taut, pacey and rigorously written, with velvet-smooth cinematography and small pockets of visual innovation including an opening credits sequence featuring words painted on the ground, with actors walking over them.

The story is unconventional in part because the violent, protocol-breaking Detective Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews) is condemned because of actions undertaken before the film commences, rather than the MacGuffin that kickstarts an “in over their head” plot. Early on the protagonist is admonished by a superior for beating people up: “your job is to catch criminals, not punish them,” he’s told. Shortly later, Dixon accidentally kills a man when he legitimately acts in self-defence. Probably correctly assuming that his superiors wouldn’t accept his version of events, Dixon dumps the body in the river, triggering an escalating series of events eventually leading to his downfall.

Stray Dog (1949)

Legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa unloads a simple, Bicycle Thieves-esque premise: homicide detective Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) has his pistol stolen from him, and spends the entire film looking for it. The protagonist goes undercover, investigating Tokyo’s black markets and follows various leads, the stakes intensifying when his gun is used on multiple occasions—one time fatally. Gripping and atmospherically staged setpieces are scattered through the runtime including one at the aforementioned black market, a baseball game attended by a suspect, and a climactic chase through a forest.

Kurosawa crafts the film with a super pulpy and pacey rhythm: bam-bam-bam, bam-bam-bam, the editing goes, scenes chopped up into small dramatic bursts that pop and fizz. Highly energetic camerawork incorporates some odd touches (such as a focus on feet and legs, a là the intro to Strangers on a Train) and keeps the audience on the edge. The plot is lean, the style is loud.