Almost 100 years on, Metropolis remains one of sci-fi cinema’s greatest spectacles

One of science fiction’s earliest and greatest films is still thrilling—and weirdly relevant—almost 100 years later, writes Luke Buckmaster.

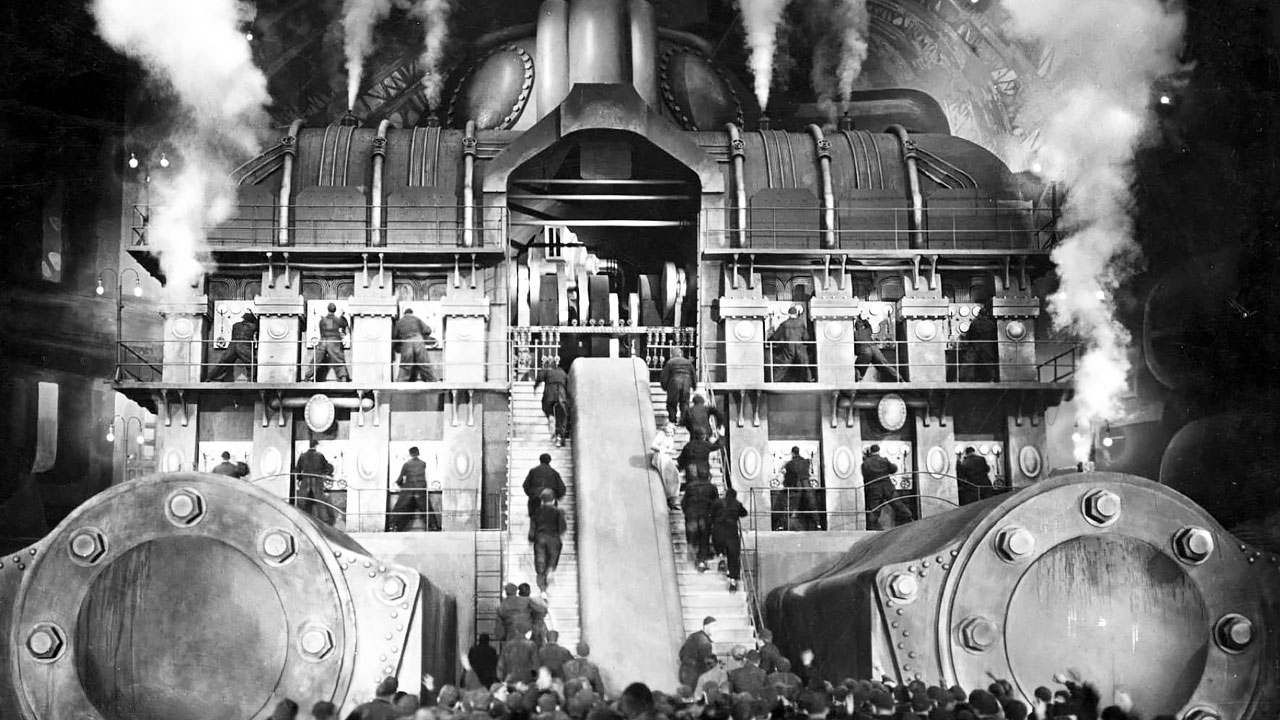

Every time I revisit Fritz Lang’s Metropolis—a film for which adjectives such as “epic” and “groundbreaking” barely begin to cut it—I am awed by its ambition, mesmerised by its visuals, spellbound by its tenacity. Watching this fascinatingly imperfect 1927 masterpiece feels like returning to a world: a haunting, expansive, eternally monochromatic dystopian future, where the divide between upper and lower class is so stark it’s become literal. The former live and frolic in glistening sky gardens, situated in the clouds far above the latter, who toil away in underground factories operating giant machines used to power the city.

This metropolis is detailed in all kinds of ratio and scale, Lang taking us up close—with mega zoomed-in images of gears and cogwheels turning—and far away, presenting iconic long shots showing the city humming and thriving from a distance, with its colossal skyscrapers and busily trafficked streets. The film’s look and feel could only come from German expressionism, the sharpness and order of its angles and architecture bent into a state of delirium through atmosphere and emotional intensity, the cityscape wobbling with tremors of madness and revolution.

The film is being remade by Apple into an eight-part TV series because of course it is, no watershed production of any kind free from pop culture’s infinite regurgitation cycle, and a modern motion picture industry churning out more and more content with less and less of it resonating. But can you really remake Metropolis? An answer in the affirmative implies one can isolate and rework a text so influential its DNA extends far beyond itself, into the lifeblood of the science fiction genre, with too many points of inspiration to count or measure.

One is its very famous robot: an android or Maschinenmensch (meaning “machine human” in German) ushered into existence by a mad scientist who tells the city’s ruler, Fredersen (Alfred Abel), that he can make it so “no-one will be able to tell a machine-man from a mortal.” The idea of a machine being indistinguishable from a person must have come across as completely batshit crazy in 1927—this aspect of the film resonating today in ways it couldn’t have a near century ago. At the core of Metropolis is an evergreen narrative, repeated countlessly in literature and subsequent films, about haves and have-nots—and a rebel disrupting the status quo.

The plot properly kicks off when Fredersen’s son Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) is entranced by a beautiful young woman, Maria (Brigitte Helm), who visits one of the decadent gardens with a group of raggedly dressed children to catch a glimpse of what life is like for the well-to-dos. She looks at Freder like an angel and he stares back, clutching his heart, transfixed. When Maria leaves Freder goes searching for her, venturing into the smoke and soot-filled bowels of the city, where workers shuffle in rows, heads down, in nondescript dark uniforms; walking almost impossibly in unison, rendered more purpose than person.

Here Freder witnesses a fatal accident (which is real, but which his mind fuses with a hallucination) that kills and injures multiple people. Freder reports the terrible incident to his father and, angered by the old man’s nonplussed response, rebels against the system and resolves to become a champion of the people—all the while chasing some skirt.

The film’s energy becomes electric when whiffs of rebellion turn into what might become a full-scale revolution, albeit with an uncomfortable twist. The inciter of the rebellion is the aforementioned robot, styled to look like Maria—who is a person of the people, seeking to unify the population through peaceful means. The droid however reflects the anger and personal grudges of her mad scientist creator, who has his own agenda, and whips crowds into fury.

Imposter robo-Maria asks: “Who is the living food for the machines in Metropolis?…Who lubricates the machine joints with their own blood?…Who feeds the machines with their own flesh?” These blood-boiling provocations verbally articulate, or at least suggest, a fusing of person and machine, which Lang depicts visually in famous shots showing men operating gigantic hands of a clock, turning and adjusting them according to the machine’s instruction.

Metropolis’ status as one of sci-fi cinema’s great granddaddies, the knee upon which so many other subsequent works have sat, is undisputed—yet it would be absurd to suggest that it’s without flaws. The plot is shaggy, great ideas come and go, the pace meanders, some so-so scenes last way too long and great moments are over far too quick. Full of religious prophecies, techno-dystopia, proclamations of doom, and even a biblical flood, the film’s messages feel like the material of a street preacher, ranting and raving, resorting to increasingly desperate measures in an attempt to hold the crowd’s attention.

But when it is great—which it often is—it is next level great. The political commentary is searing and Lang’s out of this world atmosphere ebbs and flows like a familiar nightmare, experienceable only in a half-reality or a hypnagogic state. The 1920s was an amazing era for filmmaking, with extraordinarily bold blockbusters bringing—as I have written about before—the kind of transformative change that will never come again. Metropolis is right up there with the boldest. “Inimitable” isn’t the right word, given it’s been imitated so many times before. “Unrivaled” is better.