American Primeval suggests there’s something innately inhospitable about that entire land

Clarisse Loughrey’s Show of the Week column, published every Friday, spotlights a new show to watch or skip. This week: Netflix neo-western miniseries American Primeval.

While the incoming Trump presidency, and all that it implies, threatens the future of good and honest art in Hollywood, we for now, in these dwindling times, exist in the age of the cultural consultant. It’s a specific kind of progress: good on paper, and in material benefit, yet viewed through the cynic’s eye as a convenient barrier from criticism. So what to do with Netflix’s American Primeval?

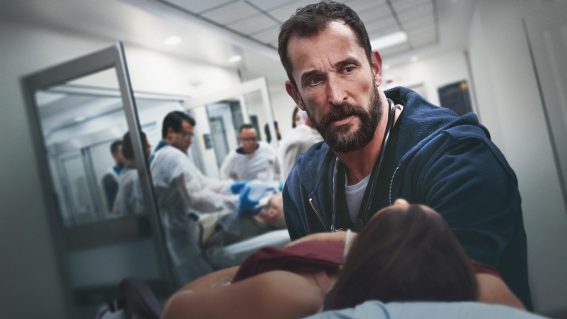

It’s an archetypal neo-western series, a macho survival epic that, visually, aches to be Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant (the two projects share a screenwriter, Mark L. Smith). Set in the Utah Territory, in 1857, it tracks four groups in conflict, as outlined by its opening credits: “The United States Army, Mormon Militia, Native Americans, and Pioneers.”

Sara (Betty Gilpin) hires a hard-edged, monosyllabic guide Isaac (Taylor Kitsch) to chaperone her and her son to the town her husband has settled in; Mormon Jacob Pratt (Dane DeHaan) searches for his wife Abish (Saura Lightfoot-Leon) after she’s caught up in the Mountain Meadows Massacre (a real historical event in an otherwise fictionalised story); while Shoshone warrior Red Feather (Derek Hinkey) clashes with his mother, and tribe leader, Winter Bird (Irene Bedard, the series MVP), over whether violent retaliation or peaceful negotiation is the surest way to survive.

Julie O’Keefe, a member of the Osage, already known for her work on Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, is credited as American Primeval’s Indigenous cultural consultant and project advisor. Her job, in reality, was to function as a kind of curator of expertise. O’Keefe sought out individuals from the three tribes depicted in the series—the Shoshone, Paiute, and Ute—who could serve as consultants, artisans, and translators. Collectively, her team produced around 3,000 costumes, set pieces, and props across three workrooms (one for each tribe)—physically separated, yet united by their ambitions.

O’Keefe’s interview with Netflix hits on the importance of her work: that in creating a wider understanding of the specific art, tradition, and language of these individual Tribal Nations, non-Native audiences can better grasp the breadth of what’s currently at stake. The intentional erasure of such key parts of Indigenous culture is a central target of any colonial and genocidal project; to respect and celebrate them in this way is to fight for their continued survival, in spite of American history’s malevolence towards their existence.

“For the 574 Tribal Nations that are out there,” O’Keefe explained. “Netflix and the team on American Primeval were advocating [for them], because they’re helping us push something that we almost lost and a lot of Tribal Nations have lost.” The work itself, of course, can only benefit, too. In American Primeval, we’re offered a world that feels real, that feels as if it has an existence and a history that extends beyond the limits of the screen and the filmmaker’s imagination.

But, then, we have to confront the other truth. Like Killers of the Flower Moon before it, American Primeval is the work of a white director, Peter Berg, known for Friday Night Lights (2004), Lone Survivor (2013), and Deepwater Horizon (2016). It’s not an incorrect impulse for these men to tell these stories (and Scorsese’s take, in my opinion, is a masterwork), and it’s encouraging to see them seek out O’Keefe’s work, and subsequently put their money back into the communities they choose to represent on screen.

Yet, the growing popularity of this kind of approach brings with it this discomforting sense that the studios and financiers—that is to say, the people who ultimately decide who gets to tell these stories—now feel like they can boast that they’ve checked all the boxes for authenticity and representation without actually investing in Native writers and filmmakers themselves.

And American Primeval isn’t perfect. In many ways, it reminds us of how much the neo-western has done to deconstruct the mythic, romanticised, ultimately white supremacist notion of “manifest destiny”, that the land America colonised was somehow owed to them, that it was a duty to tame it and conquer it. Yet, the supplanted message here is one, instead, of an equality of misery. It’s rife with violence, frequently sexual in nature, inflicted by pioneers and Indigenous people alike.

Smith’s script is not irresponsible and allows the Shoshone to vocalise that their hard existence is the direct result of American expansionism and religious fervency. But its lavishly Revenant-adjacent style, all wonky and vertiginous camera angles, makes everyone equal in their monstrosity. And its commitment to the survival genre creates the idea that there’s something innately inhospitable about this entire land, depicted always as muddy and foul, despite the fact people like the Shoshone had thrived for centuries before all this deprivation, destruction, and forced migration. I’m left to wonder how a Shoshone, Paiute, or Ute filmmaker would choose to tell this story.

Authenticity, artistic intent, and ultimate interpretation are separate states. And we should be free to criticise one, without the threat of diminishing the others—a conversation currently active in the film sphere, with the tension between the material achievements of Emilia Pérez’s trans lead Karla Sofía Gascón, and the controversial aspects of the film she stars in. Who contributes to these stories and who shapes them? What does representation mean when we talk about what exists on screen and behind the camera? American Primeval can only benefit from these kinds of conversations.