Are Mission: Impossible’s rubber mask scenes comparable to Hitchcock?

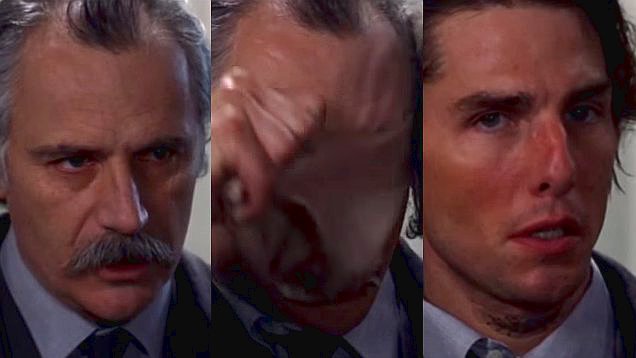

What do we make of the famous Mission: Impossible rubber mask scenes – those moments when characters rip off their faces and (ta-da!) reveal they are somebody else? Are we expected to take these moments tongue in cheek, Scooby Doo style, are we expected to take them seriously? The third movie (directed by J.J. Abrams) implies the latter, devoting a slab of running time to addressing an apparent implausibility: why people wearing these face-facsimiles also speak with the stolen person’s voice (short answer: voice-manipulating hardware).

The surprise mini revelations the rubber mask moments bring are fun, but there’s more to them than that. I love these moments for the same reason Strangers on a Train is my favourite Alfred Hitchcock film: they take ideas lingering in the subtext and find ways to visualise them.

Hitchcock’s 1951 thriller opens with low to the ground shots depicting two pairs of legs walking in opposite directions, one diagonally left to right and the other right to left. The director then cuts to two sets of train tracks crossing over each other, forming the shape of an “X.” On board the train Guy (Farley Granger) retrieves from his pocket a zippo lighter emblazoned with an image of two tennis rackets crossing over each other – again in the shape of an “X”.

All this leads up to the moment when antagonist Bruno (Robert Walker) articulates to Guy his plan for the perfect murder, involving each of them killing somebody in the other person’s life (thus eliminating motive). In his own words: “You do my murder, I do yours. For example: your wife, my father. Criss cross.” Before we got here, Hitchcock laid the foundation for concept of crisscrossing into the very fabric of the film – not just through imagery but settings, props and editing techniques.

Subtextual ideas expressed in this kind of way shows great thought from the filmmaker: a synthesis of images and meaning, surface and script. This year’s excellent and inventive comedy Game Night – one of the best films of 2018 – demonstrates these kind of feats regularly. In one scene characters communicate via charades to outsmart a bad guy. In others there are long exterior shots that shrewdly present locations in ways that make them look like elements of a board game.

The Mission: Impossible mask moments enable characters to embrace a challenge core to the story: hiding in plain sight

The Mission: Impossible mask moments enable characters to embrace a challenge core to the story: hiding in plain sight. This feeds into the franchise’s bedrock message, that the best option in life is often the most difficult – which is another way of saying that great success rarely comes easy. During the initial mission briefing in the original film (directed by Brian de Palma) Jim Phelps (Jon Voight) establishes an objective that spans the entire series when he tells Ethan: “Hide in plain sight, highest possible profile.”

The masks remind us that in this world being smart is more important than being physically strong. The very first mask scene is also one of the best. Computer hacker Jack (Emilio Estevez) looks into a monitor at fuzzy blue footage of a scene involving Russians and a man in a singlet. We naturally assume he is a long way away, observing from afar. But all of a sudden one of the men from the monitor bursts through a door just a few feet away. He rips off his mask and it’s Ethan, two small but memorable twists arriving simultaneously.

The second film (directed by John Woo) establishes that villains can play the ‘hiding in plain sight’ game too. On board a plane with a notorious scientist, Tom Cruise flashes a wicked grin that seems a little out of character. This is for good reason: we discover it isn’t Ethan Hunt but a bad guy wearing a mask of him. Later the primary villain unloads bullets into a captured and helpless Hunt. Or so he thinks. The baddie is mortified to discover he’s just killed his own right hand man (Richard Roxburgh) who Hunt gagged and dressed in a mask of himself.

The sixth film in the series, Mission: Impossible – Fallout, from director Christopher McQuarrie (who also helmed the fifth: 2015’s Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation) has been proclaimed by many reviewers as the best yet. It’s certainly an exhilarating ride (particularly the nerve-jangling finale, which crosscuts between three white knuckle scenes) but it’s also a sequel that owes a huge amount to its predecessors. The two best mask moments are both cribbed from the original movie, but hey – one can hardly blame the characters for repeating tactics that worked in previous missions.

Are the rubber mask moments the franchise’s only truly distinctive flourishes, other than its iconic theme music? I’m a fan of the Mission: Impossible movies, but that is not the same as saying their many thrills and spills are original, or even intend to be. The playful use of masks throughout the series is one thing that separates the MI brand from the pack. These moments may not pry open the subtext as precisely as Hitchcock’s compositions, but they work in a different way – prioritising action over images.