The Film Buff’s Guide To Spotting Bad Movies

Joel Schumacher's classic clusterfuck: "Batman & Robin"

(An apology for very little blog activity last month — working in the film industry means that sometimes there is just no time to have to yourself to get these things out. It is, indeed, a harsh mistress. Anyways, everything should be back to normal this month!)

*ahem*

Tired of wasting your money from one terrible movie to next? Wishing you hadn’t spent your last buck on that latest modernized, re-envisioned, prequel reboot of that old Hollywood film adapted from that television show franchise? Ever wonder how movie buffs manage to see so many good films, stay so excited about movies, but somehow not spend all their disposable income on the bad ones? Well wonder no more, the answer is at hand, because this is the handy-dandy, automatic, state-of-the-art, cutting-edge, all-encompassing and comprehensive guide on HOW TO SPOT A BAD MOVIE (AT A DISTANCE).

Bad movies are, of course, something that is subjective on its own. What constitutes a ‘bad movie’? Are some films worse than others, or are all bad movies just awful in their unique way? Are all bad films bad for everybody? Don’t film buffs like bad movies too? What about bad films that you love to watch because they’re so bad? Where do you draw the line? The answers to these questions are, of course, equally subjective. YES – film buffs do indeed love many bad and terrible films. YES – some bad films are considered to be great films by others. YES – films aren’t made ‘bad’ in the same way. YES – guilty pleasures are a legitimate argument against the notion of ‘bad films’ because how can a film be truly bad if someone actually genuine connects with it in some unexpected way?

But that doesn’t mean that you can’t create guidelines or pathways to navigate your way through the World Of Movies: arguably the king of the expressionistic artform alongside popular music. These guides are not about telling you which films are good or bad, but advising you on what to look out for in order to discern your own particular brand or type of film quality. With the information in this article, perhaps you’ll be able to draw your own unique map of cinema and figure out what it is that excites you about movies, what turns you off and how to judge films (without actually seeing them) to figure out if its worth your last few dollars till next payday.

LESSON ONE

Mediocre Films Can Be Worse Than Bad Films

As we’ve established already, film buffs definitely LOVE ‘bad’ movies. The notion of the guilty pleasure is modified by a factor of ten when it is the guilty pleasure of a film nut and there are so many wonderful bad films that people will watch again and again with maximum enjoyment and not a shred of regret. Popular ‘bad’ movies include things like the filmography of Ed Wood Jr (famously Plan 9 From Outer Space), low-budget foreign horror or martial arts films from the 1970’s and 80’s, Exploitation or Blaxploitation films, B-movies from the 1950’s, amateur films that somehow got widespread distribution (e.g. the craptacular Birdemic or Tommy Wiseau’s The Room) or just terrible films with such notoriety that transcend their bad-movie status into a cult phenomenon.

Perhaps it’s within our own human nature to feel something for these underdogs of the cinematic world (whether a nurturing sense of empathy or just cruel, mocking, schadenfreude) and we gain genuine respect for these people who try to make a film and screw it up so spectacularly that it becomes an unforgettable experience that has to be seen and appreciated over and over again. Whatever the reason, badly made films are not necessarily bad films from the perspective of an audience.

Sho'Nuff has got 'da glow' in the so-bad-its-great film: "The Last Dragon".

Mediocre films, on the other hand, are completely different animal. Mediocre films are what, I think, really piss people the hell off more than anything else. Why? Because it’s not about watching incompetence or inexperience flounder helplessly across the screen for your amusement, it’s about people who ARE skilled and ARE experienced and SHOULD know better, but still land turkeys on your lap and suck up your precious life minutes and cash in the process. Mediocre films are the bland, middle-of-the-road, predictable, forgettable, phoned-in, tapped-out, factory-produced, cookie-cutter, brain junk that litter the shelves of your DVD store or fill the gaps between the once-in-a-while genuine phenomenon films of our time. Mediocre films can be anything from low-budget indie fluff to mega-epic tentpole blockbusters; it’s not the size of the budget or the saturation of its market presence that counts, only the fact that you walk out of the movie and have that “was that it?” feeling. I don’t need to give you examples as I know each of you have your own private library of ‘movies you regret seeing’ in your head as reference.

Jack Black and Michael Cera. Surely hilarity must ensue?

The problem then occurs that mediocre films, being often made by ‘competent’ filmmakers, are also sold to you by competent marketing teams. These films are rarely tiny indie features that you hear about from word of mouth, they’re more often the films that are bombarded to your face at every bus-stop or in every commercial break or in every other pop-up ad. This is because mediocre films use the law of averages to make their money back; its the industry of making something that’s good enough to attract attention whether or not it delivers the goods. And since a lot of mediocre films – particularly out of Hollywood – are purely ‘vehicles’ for merchandising, stars, tie-ins or capitalizing on something that is genuinely popular at the time, there is no imperative for that film to be a piece of classic cinema…which then just drops the bottom out of the quality threshold altogether.

So how do you wade through hundreds of millions of dollars of marketing fluff to guesstimate whether a movie will ultimately be worth your fifteen bucks?

LESSON TWO

Know Where The Talent Lies

Because I keep running into people who never have used or seen this website, despite the fact that it is one of the oldest, still running, commercial websites on the internet, I will have to plug it here. This is the Internet Movie Database:

And it is your one-stop-shop in finding out anything and everything about the world of film. It is a repository of information pertaining to cast, crew, trivia, box-office, ratings, budget and a lot of other information about movies. ALL MOVIES. In all languages, from all countries – at least that have received some form of distribution. There is even an ‘industry’ version called IMDBPro.com which is the number one online tool used by professional filmmakers in Hollywood and beyond (if you’re a filmmaker and you don’t have an account, then GET ONE because you are missing out!).

Screenshot of the IMDB (old layout, this has been changed radically)

And the Internet Movie Database should be YOUR tool in getting the facts on a film before you give it your time, money and attention. Why? Because as films have progressed over the last twenty years or so, it has become more and more apparent that the quality of a movie is no longer determined by its star or cast or concept or genre or studio…its determined, ever increasingly, by its writers, directors and producers. These are the people who control the creative channels and floodgates of a film and are the ones who, fairly, should get the blame when things don’t fly the way they’re supposed to.

If you’ve never paid attention to a film’s director or writer, then this should be an interesting exercise for you. Go to the Internet Movie Database, search for one of your all-time favourite films and see who the director was. Now click on that director’s name and you’ll get a list of everything else they’ve made. Now see if anything else on that list also is a favourite film or at least a film that you enjoyed greatly. More often than not, you will find that your favourite movies have strong commonalities which run along the lines of the men and women who wrote, directed and (sometimes) produced those films.

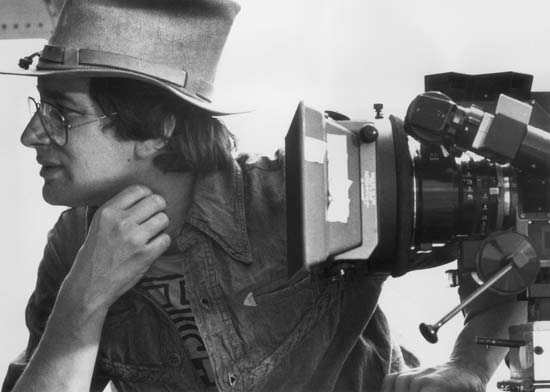

Steven Spielberg: arguably still the most famous director alive today.

The director is often the person who will get the most credit for a film’s success. While there are always exceptions, in most cases the director exerts the most control over the look, feel, shape, pace and general quality of all of the film’s elements. Because of this, a young film-buff in training will soon find that there are some directors who produce film after film of cinematic gold that they just can’t get enough of. A person’s favourite director often will be someone who produces a level of quality that they can rely on and get excited about, like seeing the next oasis appear on the horizon after weeks in the desert. There are many directors who are also reknown for being consistent in their quality of work and become superstars in their own right, particularly when their films change the course of human pop culture as we know it. Learning to spot good directing in a bad film can be difficult however the general measuring stick tends to be: “stupid movie, but still entertained the hell out of me” which suggests that a film that had poor elements still managed to hold your attention because the director (or sometimes a producer running a creative intervention) managed to fit all the wonky bits together into a cohesive whole that excited and engaged you. At the end of the day, the single most common element found within the perceived quality of films tends to be directly tied to the person who directed it.

Producers don’t really get much creative credit for a film by audiences though they do take home the most money and get to collect the ‘Best Picture’ Academy Award if they win. It’s hard to describe what producers are because their roles are so different from film to film, but the analogies that work best are the ‘housing’ example (the producer is a client who wants a house built to their specifications and supplies the money and building materials, the director is a combination of architect and chief builder who actually creates the building for the producer) or the ‘cruise liner’ example (the director is the captain of a cruise liner who decides HOW the journey across the ocean should be undertaken, while the producer is the owner of the cruise-liner company who manages all the resources and tells the director WHERE to take the ship). Producers do get to share a strong influence over the creative direction of a film (after all they ARE usually the ones paying for it) and today there are some producers whose influence is so strongly felt in a movie that they often overshadow the fame and power of the directors of those films. Of course the best example of this in today’s context is Jerry Bruckheimer: a man who even manages to get all of his films (from Flashdance to Top Gun to The Last Boy Scout to Coyote Ugly to Pirates of the Caribbean to Prince of Persia) to have almost identical cinematography and art design. Don’t believe me? Check this shit out:

Producers are never the be-all and end-all of creative quality in a film as, unlike directors, there is very little perceived consistency by the audience of a producer’s influence. There is rarely one thing that you can point to a film and say “that was well produced”, but at the same time there is unmistakable pattern that appears when a director and producer consistently make great films together, but – when separated – produce work that lands squarely in the ‘mediocre’ range. Whether or not you may feel a movie’s producer is important, fair warning is still given; if you want your films to be loud, angry, violent and make no logical sense whatsoever…then you can pretty much bet on anything J.J. Abrams has ever had a producing role in.

Then there’s the writers. These poor people have it rough. Historically they get blamed for a lot, but often have very little control over the quality of the final film – especially in today’s modern Hollywood brainfarts where apparently you can have a film that has fifteen writers and still produce story and dialogue that your average high school student could pick apart with no effort. Good writing often comes down to the nitty gritty bits and pieces of a film – the dialogue, the way information is given to the audience, the way characters react to situations and the overall story and how believable it all feels. The addition of a good writer, whose quality work makes it to the screen, can turn an otherwise forgettable film into a masterpiece. Examples of this could be the work of Academy-Award winning writer Paul Haggis in the greatest James Bond film Casino Royale (if you want to see what he contributed, watch the sequel Quantum of Solace which had all the writers from the previous film EXCEPT Haggis), Jonathan Nolan in The Dark Knight (who replaced studio-hack writer David Goyer who was responsible for Batman Begins) or Richard Curtis (who almost single-handedly launched the goliath UK rom-com industry with Four Weddings & A Funeral, Nottinghill and Love Actually after conquering UK television with Mr Bean and Blackadder).

David Goyer: if he didn't already have the worst job in the world, I would hate him SO MUCH.

But these are exceptions to the rule – good writers don’t last very long in Hollywood and, more often than not, the writing credits of a film are where you have to keep your eyes peeled for the nefarious studio hacks (by definition – people who can write drafts of scripts on time, on budget, exacting to studio notes, but with very little emphasis on panache or quality) who are dominating the industry more than ever. Most of the big tentpole blockbusters of the last ten years are written by two-to-five man teams of mediocre writers on semi-crummy paycheques…and coincidentally these will most likely be the same blockbusters that had stories which made no sense, characters that failed to follow logic or just plot twists and dialogue that made your head ache while you enjoyed the nice explosions and special effects. In Hollywood, the more expensive a film is, the more likely the writing team will be a team of poor schmucks who are denied the time and freedom to write beautiful, strong scripts that audiences need just to make the story make SOME KIND of sense.

Often this isn’t on purpose or due to a lack of talent, but because of strong creative interference run by a studio who are not willing to take risks on films that they’ve sunk $300 million into and know that the movie has to appeal to the widest demographic possible to make its money back. And don’t get me wrong, these notes are not always outlandish or insipid, but can be made by creatively talented people who feel that they are whipping the film into the best direction possible. But as anyone who writes for a living can tell you, sometimes the best writing is built like a house of cards and removing one element can collapse the whole structure – to properly rewrite something you have to, often, restart from scratch…but the movie development process doesn’t allow you enough time to do this and so you end up with a patchwork, over-simplified script with glaring logic and plot holes rather than a finely crafted story that’s been distilled over a period. Studio hack writers, in particular, make a living in this arena as they are noted for being able to change scripts with (seemingly) minimal damage and do it on schedule and on budget which is why film producers love to use them all the time.

Suffice it to say, when it comes to writers, you need to know your hacks and teach yourself to withhold your curiosity if there name crops up on the credits. For me, the screenwriters that brought me Terminator: Salvation, The Transformers, Star Trek and Indiana Jones & The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull are on my ‘do not watch’ list. Who would be on yours?

LESSON THREE

Stars & Star Vehicles

The law of popular filmmaking is that every movie needs a star. Why? Because filmmakers ultimately concede that audiences will always be swayed by the presence of an actor or actress that they like or have seen in ‘something good’ and will more than likely project that emotional connection onto the film that they’re currently making. Like Colin Firth? Seen a lot of good Colin Firth films? Then you are, automatically, more predisposed to project all your good memories about Colin Firth onto the new movie he’s acting in, even if THAT films happens to be directed by a team of blind chimpanzees using a script written by 5 year old with crayons on the back page of a coloring book. And if your expectations aren’t met by the film? Well too bad, they have your money already.

Believe me, I know how he feels.

Stars are more than just actors, they are – arguably – the world’s first visual effect. The same psychological process applies if you are excited about the latest big budget special effects film as it would be for someone excited about their favourite star’s next film. The presence of a star in a movie is to guarantee a minimum number of seats in theaters or rentals on DVD/Blu-Ray or Video-On-Demand. The marketing of a film will then monopolize on star presence to get you into the theater on opening weekend as studios (in particular) exercise a smash-and-grab philosophy for box-office returns especially when they know their product is mediocre and not likely to generate repeat business. The methodology is simple: tease, intrigue, seduce or outright subvert as many people to watch the film on opening weekend as possible and earn as much money before those people discourage their friends to see the film. Get them in, take their money, get the hell out and hope that your opening weekend will be strong enough to get you ‘over the line’ so that you’ll make pure profit by time the film is released on home video. And although their power is waning spectacularly (Tom Cruise’s last film: Knight & Day suffered the worse opening for a Cruise film in decades), stars are still one of the most powerful tools a film has to convince you that it is worth seeing.

And just as some movies seek to purely dazzle you with visual effects to get you into the theaters (say for instance Roland Emmerich’s 2012 or Godzilla), other films will seek to dazzle you with the inclusion of a megastar (who is too-often miscast in that film to begin with). These are called ‘star vehicles’: movies that solely exist because they rely on a star to reach out to the audience and give a film credibility. Star vehicles are often perpetuated by a star in the first place and, until recently, most megastars owned their own production company whose staff was dedicated to finding scripts and getting movies off the ground for that actor or actress to appear in. Star vehicles are notorious for obfuscating a film’s worth behind the dazzling mug of a leading man or lady who carry the entire film’s weight on their shoulders. Take this film for example:

Notice how the star's name is bigger than the movie's title.

Now I know that, for some of you, I Am Legend isn’t a bad or mediocre film. That’s fine, I’m not here to tell you that it is, I’m only using this as an example of a mediocre film for me. Statistically the film’s performance was good — it hovers around the 69% fresh mark on Rotten Tomatoes (suggesting not a great film, but solid) and its returned over $600 million internationally on its $150 million budget plus $100 million prints & advertising spend. Getting down to the nitty gritty, the film definitely has problems as a lot of people complain about the movie’s deflated and almost nonsensical ending, its dodgy ‘creature’ effects and most reviews agree that it is Will Smith’s performance that makes the movie worthwhile. I would agree with these qualitative reviews, having seen the two previous versions of the story The Last Man On Earth and The Omega Man plus being a fan of the original novella which arguably is the sole inspiration of the modern ‘zombie’ craze as it also inspired Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead. The Will Smith film is nothing to rave about and, at times, its pretty shonky and melodramatic and retains almost nothing of the original novel’s writing quality.

But that’s okay because the filmmakers did not rely the novel or the creative team to sell the film. They relied on the name-brand of Will Smith to get you into the theaters. Look up I Am Legend on the IMDB and check out its crew: the film was directed by Francis Lawrence, who’s only prior credit (bar music videos – another sign of trouble) was the luke-warm thriller Constantine. In fact, Constantine is a perfect mirror image of I Am Legend in many ways: built solely around a star, drifts far away from its original source material (Alan Moore’s Hellblazer comics which instantly turned many fans of the comic away) and is a mediocre supernatural thriller that is unadventurous, run-of-the-mill, forgettable, but not badly put together. Then look at the film’s writing team which features one Mark Protosevich who penned the story-lite Jennifer Lopez star vehicle The Cell and the awful disaster remake Poseidon and famed studio hack Akiva Goldman, writer of Batman & Robin, Lost In Space and The Da Vinci Code. The waters of creative expectation suddenly become very murky when you look at this team and then look at how big Will Smith’s name is on the poster…and realize that, whether it was the intention of the studio or whether its just that things worked out that way, Smith’s name was needed to pull an audience in because the writers and director sure as hell wasn’t going to do it. And that is a ‘star vehicle’.

The lesson here is simple: the bigger the star and the bigger the name of the star on the marquee, the closer you should look at the writers, directors and producers before deciding whether the film will be worth your money.

LESSON FOUR

Marketing Is War

Marketing has always been a battleground for the world of media, but in the world of movies it’s all out thermonuclear war. Film production companies work hard to vie for you buck, insisting that you should see their film above the competitors that are opening in the same day, week or month. In mainstream, tentpole, blockbusters; a studio can spend on average as much as 70% of the film’s original budget on just advertising (so a $150 million film could have a marketing budget of as high as an extra $100 million). In the word of films, this is where the hearts and minds of the audience can be won or lost before the movie has even opened.

There are many tools and tricks of the film marketing trade designed to create the illusion of quality when the reality may be the exact opposite. The first is the most obvious: posters and trailers. Posters – they tell you nothing. There is no correlation to a film’s quality based on its print advertising, it is impossible to judge a film by its (almost literal) cover. Skip the posters. Trailers are a bit more telling. Trailers are now an absolute artform to itself and could almost be judged as mini-movies in their own right. Some of the worst films I’ve ever seen have some of the greatest trailers known to man (check out this beauty for The Mummy which tries to sell the audience that its Bram Stoker’s Dracula meets Raiders Of The Lost Ark…or we can just go for this amazing piece of work for a movie in theaters right now that people are describing as “well it didn’t suck as much as the last one.”). Trailers are now all about the tease, the seduction, the whispers and promises a film makes about the experience you will be in for. Like that person who’s always trying to seduce you into bed, trailers can be the expensive restaurant and moon-light walk before the ‘main event’. There’s no point in me breaking the art of trailers down for you, since The Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy movie did it expertly for us in their own trailer.

There are of course things to look for in a trailer, but these elements often more visible once you know enough about your favourite (or hated) director’s work to ‘spot the tell-tale signs’. In the case of Michael Bay’s Transformers 3: Dark Of The Moon, the lack of dialogue or story exposition in the trailer was a bad sign, but the fact that the ‘hot babe character’ doesn’t utter a single line or do anything apart from look up at Shia LeBouf with a desperate expression of ‘save me please’ pretty much sold me that I was to expect nothing more than Bay at his worst…and reviews of the film so far suggest to me that I was probably right in my estimation.

And then there’s my favourite tool which is getting used A LOT these days and A LOT of people continue to fall for: the executive producer credit. Case in point, the biggest criminal of this particular nefarious cheat is Mr Steven Spielberg himself who, to date, holds an astonishing 102 Executive Producer credits on films, television shows, computer games and even music videos. On some films, his executive producer credit precedes the director’s name (case in point: the Transformers saga) on trailers and posters, as if to say that the magic joy-juice of Spielberg has been liberally splashed on all of these fine products and double-checked for qualitative goodness…films like Joe Vs The Volcano, Family Dog, The Flintstones, Casper, Balto, Evolution, Eagle Eye, Men In Black II and much, oh so much, more.

Oooh, executive produced by Ridley Scott!

Let’s get this one straight once and for all. Executive Producer credits are not the same as producer credits or director credits or any other kind of ‘creative’ credit. Executive producers are people who played a pivotal role in getting a film ‘off the ground’ as it were, often in a signed-the-cheque, introduced-the-right-people-to-each-other, did-someone-a-huge-favour, came-up-with-a-one-sentence-story-pitch or just, outright, got-paid-to-have-their-name-slapped-on-the-movie capacity. The exec producer credit is a stand-in for thanking someone who did something for the film that resulted, usually, in them getting a chunk of the profits at the end of the day. There is rarely any significant creative role that an executive producer plays in a movie. Unless you hear differently, you can assume that anything Steven Spielberg executive-produced has about as much authentic Spielberg-magic as the $5 Rolex you bought in that Thai flea market has authentic Swiss machine parts inside. The reason why – for instance – Spielberg’s name is on The Transformers movies has more to do with the fact that his studio Dreamworks is footing half the bill for the franchise than it does with the fact that Spielberg sat next to Michael Bay and ‘guided his creative vision’ into the movie (presumably by inserting those trademark Spielbergian masturbation jokes and upskirt shots of women’s bottoms).

The Executive Producer credit monopolizes the audience’s lack of understanding for movie terminology to create a false impression of credibility. The credit is absolutely meaningless unless there is significant evidence that suggests otherwise. If you exercise caution with films that have your favourite filmmakers in executive producer roles, you’ll save yourself a lot of money and time feeling cheated or let down.

Wow...just LOOK at that header on the top of the poster. Magnificent.

The other one of these to avoid is the ‘From The Makers Of’ credit that you see on posters and trailers. This one is a very clever bit of double-speak that actually means: ‘From the people who were involved in X great film, but didn’t actually creatively drive or contribute much to said film’. Often the ‘makers’ will be executive producers or co-producers or, at a real stretch, a studio or financing body that greenlit said ‘previous awesome movie’. ‘From The Makers Of’ is an attempt to bestow the current film with the credibility of another film which its prime creatives (producer, writer and/or directors) are not involved the current film whatsoever. It’s just a technique to cash in the name of another film just because someone in your production team had some vague loose connection and got a credit on that movie. Don’t trust the ‘From The Makers Of’ credit. Ever.

LESSON FIVE

You Can’t Always Win

The final lesson in this is that you can never really be immune to the power of mediocre or genuinely bad (and boring) films. Here I offer myself as evidence.

Casino Royale, directed by New Zealander Martin Campbell, is one of the greatest genre films ever made as far as I’m concerned. As someone who’s not particularly fond of secret agent James Bond, it is the single-greatest Bond film ever made (and rest assured I have seen them ALL). Martin has directed a few other films that I don’t have much interest in like Vertical Limit and the two recent Zorro franchise films, but Casino Royale made me into a believer.

Director Martin Campbell on the "Casino Royale" set with Daniel Craig.

Something else that also made me a believer was Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight. I’m a DC boy, I’ll say it hear and now. I don’t disrespect Marvel – comics or film franchises – I just find it hard to relate to the continual, twisting, superhero soap-operas that dominates Marvel storytelling. DC comics are mythic, they are comics that act as a mirror for ourselves, the best heroes in DC comics say something about us as people and how we relate and aspire to defeat the negative aspects of our society. Marvel isn’t…and that’s fine, different strokes and all that. But DC’s had a bad rep when it comes to cinematic adaptations and frankly I had no hope for the company until The Dark Knight rose out of the shadows and rocked my world (as well as a lot of other people’s).

So imagine my delight when I hear that they were finally making a Green Lantern film. With Superman and Batman seemingly ‘taken care of’, I’d always dreamed of the chance of helming a Green Lantern movie and while that opportunity has now been snatched away, in my post-Christopher-Nolan hype I had envisioned wonderful things for one of DC’s most under-appreciated and overwhelmingly interesting heroes of all time. And so I start doing my homework…

Okay, so the star is never a gauge of quality, but Ryan Reynolds is a talented and hardworking actor. From the first time I laid eyes on him in Two Guys, A Girl & A Pizza Place I knew he a magical ‘something’ about him that make him a star that would be worth one’s time to follow. He’s a pretty good fit for the lead and has the potential acting chops to make the role really work. Then there’s Martin Campbell…okay I’ve only really loved one film he’s done, but that film is one of my all-time favourites. Surely with the right producer and writing team, Campbell could land another mindblowing film, right? Then the writing team – all four of them – glanced over my IMDB search page…two guys who’ve written ONLY for television, one who’s written for freaking video games and one actual experienced screenwriter…whose work is average at best with a Harry Potter film and a terrible Peter Pan adaptation to his credit. And the film’s lead producer? His filmography includes Yogi Bear, Without A Paddle and Burlesque.

I should have known better.

When the poor reviews started flooding in, inciting problems with the script and the film’s presentation in pretty much the ways that I had feared (despite being somewhat giddy about the 2nd and 3rd trailers of the film….yeah yeah I didn’t follow my advice), I still held out. I still had hope. I still had faith. I still thought that maybe it’ll be one of those guilty pleasure films that I’ll enjoy even if nobody else did.

I should have known better.

And then I went to the cinema. I coughed up my $20 for the non-weekend 3D session. I bought my over-priced drinks and food, sat in the dark, put on my glasses, and waited…

I should have known better.

And now those bastards have my money and 2 hours of my life I’ll never get back. The final lesson is this: they will always, ALWAYS, find a way to break through your critical reasoning and rob you of your time and money. That’s life and in life you can’t expect to win all the time. And if you find that happening to you, all I can ask is that you don’t be too hard on yourself. We all make mistakes, we all have dreams and yes, sometimes, we just need to ‘veg out’ on something utterly mediocre just to let our senses rest or our reasoning to take some time out.

At the end, we must always remind ourselves: it’s just a movie after all.

Thanks for reading.