Cursed, evil and adored – dissecting what makes The Exorcist so terrifying

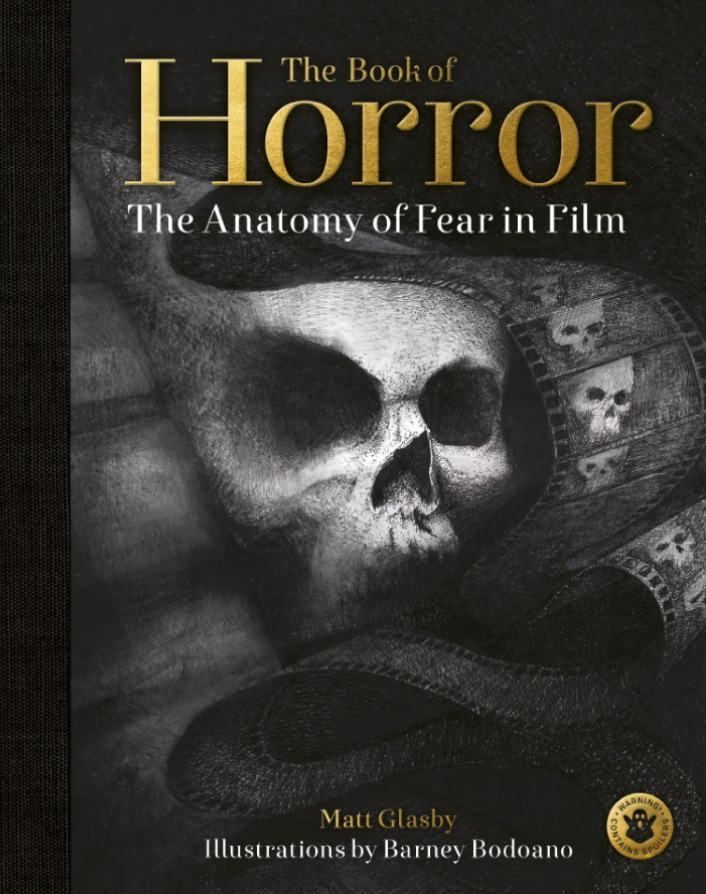

A new book from Flicks contributor Matt Glasby (now on sale) peels back the layers of the most frightening films of the post-war era—from Psycho to It: Chapter Two—examining exactly how they scare us. In this excerpt, Glasby explores The Exorcist—one of the most storied horror films ever made.

The Exorcist might be the most storied horror film of all time. Directed by William Friedkin from a script by William Peter Blatty, who also wrote the 1971 novel, its production involves so much myth-making it is hard to unpick the fact from the fiction. Upon release, it was supposed to have caused fainting, vomiting, even heart attacks among audiences. It was cursed, the crew said; evil, according to preacher Billy Graham; banned in England and Australia.

See also:

* The 25 best horror movies on Netflix Australia

* The 10 best Australian horror movies of all time

Although the film’s grip has lessened over the years, thanks to numerous alternate edits and sequels (the best of which is Blatty’s The Exorcist III), what charge remains comes not from Dick Smith’s game-changing special effects, but the fact it is grounded in the real.

Inspired by the exorcism of a fourteen-year-old boy that took place in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., in 1949, it tells the story of Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair), the 12-year-old daughter of actor Chris MacNeill (Ellen Burstyn). While her mother is shooting in Georgetown, Regan becomes possessed by an ancient demon (named Pazuzu in the 1977 sequel), who must be cast out by troubled priest Father Karras (Jason Miller) and the eponymous Father Merrin (Max von Sydow).

When we first meet her, Regan is just a normal little girl who wants a pony and reads movie magazines (admittedly, ones with her mother on the cover). As it turns out, it is not Regan the demon is interested in, but Father Karras, who is losing his faith after the death of his mother (Vasiliki Maliaros). Still, the muddy motivations take several viewings to make sense of.

Friedkin, known for his uncompromising directorial style, favoured gritty realism over Hollywood flash. “When I saw the files at Georgetown University pertaining to the actual case, I knew that this needed to be something more than just another horror film, this had to be a realistic film about inexplicable events”, he explained in the Bluray introduction. Indeed, what makes viewers so pliable once the puke starts flying is that, for half its runtime, The Exorcist is essentially a drama about a very ill young girl at the mercy of modern medicine.

Although draggy by today’s standards, and full of details that are only explained elsewhere, the early sections of the movie are dusted with dread. In a lengthy prologue, when Father Merrin contemplates a statue of the demon Pazuzu in Iraq, the soundtrack buzzes with bees. At Chris’s Georgetown house, meanwhile, we see the wind scattering the leaves as if strange forces are brewing. Regan, we learn, has been playing with a Ouija board, talking to an invisible friend called Captain Howdy, and feeling her bed shaking at night. But these details are mentioned so breezily that the film’s first foray into the grotesque is doubly shocking.

At a party held by her mother, full of movie folk, priests and D.C. movers and shakers, Regan sleepwalks downstairs, tells an astronaut (Dick Callinan) “you’re going to die up there”, then urinates on the rug. That night, Chris sees Regan’s bed bucking like a wild animal as her daughter screams. Later, at the hospital, we watch Regan pulled, prodded and penetrated by doctors, including undergoing a (purportedly genuine) arteriogram, which looks like the modern equivalent of medieval bloodletting.

Seeing a young girl leaking what appears to be real blood primes the viewer’s fight-or-flight instinct, leaving them more vulnerable to the supernatural shocks that come next, so it is no wonder that people reported experiencing physical responses. Even Blatty confessed to finding the scene difficult to watch.

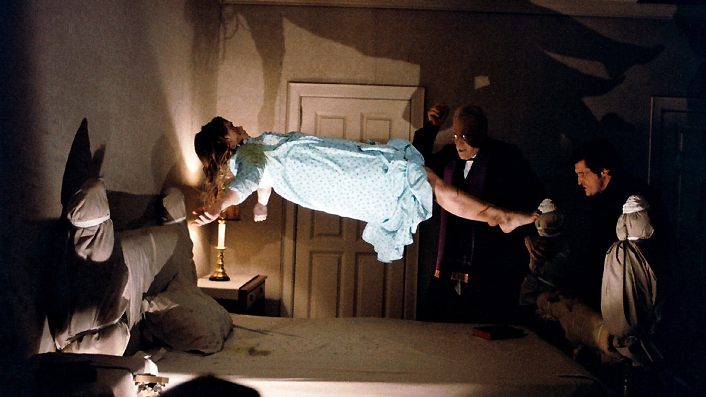

As he told the BBC documentary The Fear of God, “The film has a power to move you and have a disturbing effect on the viewer, which is greater than the sum of any of its parts.” After a careful build-up, all hell breaks loose, with Friedkin using every trick at his disposal to create the sense that monumental evil has been unleashed before our eyes. Once Regan is fully possessed, there’s no dead space, no dark corners to hide in: everything takes place in plain sight, often with practical effects performed ‘live’ on set.

“I was presented with the problem of taking this 12-year-old little girl, a very pretty little girl with apple cheeks and a butterball nose, and making her into a demon,” recalled make-up artist Dick Smith in The Fear of God. Early tests were unsuccessful, until Friedkin hit upon a more realistic solution.

“The situation should come from something that Regan did to herself,” he said. “I thought, what if, in the scene where she’s masturbating with the crucifix, we saw that her whole face was streaming with blood, fresh blood, as though she had used the crucifix to scar herself?”

Besides offering all manner of repulsive details—milky white eyes, black snaking tongue, a throat that bulges like a serpent consuming its prey—and moments of blasphemous shock, the special effects are so effective because you can feel them. When Regan vomits green bile (actually pea soup) at the priests, it steams. When holy water splits her skin, or she jabs a bloody crucifix into her vagina, it looks like it really hurts. Besides, having seen ‘genuine’ blood in the hospital scenes, how is the audience expected to know the difference?

While the film can, at times, feel like a full-on assault of the senses, some of its best scares operate on a subtler register. Asked where Regan is, the demon replies, “In here, with us!”, the uncanny 6 choice of words matched by some extraordinary vocal work. At different points we hear Regan growling, wheezing, roaring and speaking in tongues to suggest that Pazuzu’s power is truly legion.

Mostly this is down to voice actor Mercedes McCambridge, who recorded the demon’s dialogue after consuming raw eggs, cigarettes and whiskey while lashed to a chair—if rumours are to be believed.

“Basically she performed it under great duress and I was stunned at what she allowed me to put her through,” admitted Friedkin.

Another famously uncanny moment is when Regan’s head twists round 180 degrees, a grin of impish malevolence frozen on her face. Although the model work becomes less convincing the closer you look, what sells the effect is the sound—actually foley expert Gonzalo Gavira, who had impressed Friedkin on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo, crinkling a cracked leather wallet into a microphone.

Over the years, the film has caused much furor due its use of near-subliminal images and noises, which must have been even more effective before the advent of home video. During a mournful dream sequence of Father Karras’s mother emerging from the subway, Friedkin inserts a flash of Pazuzu’s alarming, black-and-white visage—actually an outtake from make-up tests performed on Blair’s body double, Eileen Dietz. Later, Friedkin flashes the same image during the exorcism, then again, overlaid on Regan’s face as she looks right at us as in Psycho.

The sound affects our fear responses in more mysterious ways. Throughout the film Friedkin makes use of industrial noises, pigs squealing on their way to slaughter, and thrumming insects—all designed to make viewers feel tense, however unconsciously. Even the theme music, taken from Mike Oldfield’s 1973 prog-rock hit Tubular Bells, is in an unsettling 7/8 time signature. Together, these elements cohere to create the sense that there is something unnatural in the very fabric of the film itself.

But the main reason The Exorcist remains so effective is less to do with evil than with pain. While shooting, both Burstyn and Blair suffered real back injuries that Friedkin decided to keep in the film. The director also slapped Father William O’Malley (Father Dyer) before a take, fired blanks from a gun to shock Jason Miller, and god knows how McCambridge, a recovering alcoholic, reacted to his brand of ‘duress’.

Clearly this kind of behaviour is unconscionable, but it dovetails exactly with the pain the characters are experiencing. Regan’s arteriogram is, if Friedkin is to be believed, the equivalent of snuff cinema. When she is splashed with holy water she screams and screams in agony. Once it is all over, she huddles in the corner crying, and her mother—for one awful second—hesitates before comforting her. Watching another soul in pain, it seems, is pain enough for us all.

Further viewing:

The House of the Devil (2009)

Beginning with some slightly dubious statistics—apparently, more than 70 percent of Americans believe in Satanic cults—and based on ‘unexplained’ (because fictional) events, Ti West’s slow-burner could have easily been a short. Although 1980s acolytes will relish the period detail—a cassette Walkman, double denim, a cameo from genre favourite Dee Wallace—the story is bare bones at best.

Against her better judgement, broke student Samantha Hughes (Jocelin Donahue) is hired by the mysterious Mr Ulman (Tom Noonan) to look after his elderly mother in an old dark house during an eclipse. Obviously this is a bad idea, but there is something about the build-up, all long zooms, wide-open frames and mounting unease, that makes the resulting tension feel merciless rather than manufactured. Indeed, viewers would be forgiven for jumping in shock when the pizza boy arrives, let alone when eye-popping violence eventually explodes.

The Last Exorcism (2010)

Daniel Stamm’s found-footage horror offers a clever take on Friedkin’s classic. Charismatic Baton Rouge preacher Cotton Marcus (Patrick Fabian) agrees to let film-makers Iris (Iris Bahr) and Daniel (Adam Grimes) follow him as he demystifies the exorcisms he performs as acts of religious showmanship. But when he is called to Louisiana to help poor, seemingly possessed Nell (Ashley Bell) and her family, Marcus finds his usual tricks do not work.

The roving camera provides several freaky moments, such as when the crew search for Nell only to find her perched on top of the wardrobe, staring into space. Later, a scene of impressively horrible contortion sees her bent over backwards in the barn, breaking her own fingers one by one. The final act’s mad conflagration has been criticised in some circles for ruining the cerebral scares, but it makes for a memorably high-impact ending, shouting a lot louder than Friedkin’s all-back-to-normal approach.

The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014)

Gerontophobia, or the fear of the elderly, provides the pulse of Adam Robitel’s sophisticated debut, which shares DNA with M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit. Mia (Michelle Ang) and her crew are PhD students making a video thesis on dementia; Deborah Logan (Jill Larson) is their subject, an early-stage Alzheimer’s sufferer beginning to act erratically much to the consternation of her daughter Sarah (Anne Ramsay).

Because the symptoms of her illness—physical deterioration, hallucinations and violent outbursts—are broadly the same as those associated with possession, what follows is doubly distressing. Even before any supernatural interference, the ravages of the disease are as obscene as any horror film. The found-footage format makes excellent use of dead space as the crew search Deborah’s house during her many night-time rambles, and there’s a near-subliminal insert of a snake-faced man—the real villain—slyly edited into a blank frame.

More

See All