From If Beale Street Could Talk to Boyz N The Hood: African American auteurs and their greatest films

![]()

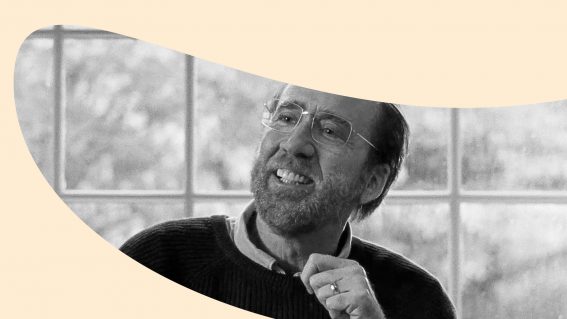

If Beale Street Could Talk is the latest film from director Barry Jenkins, one of the most vital voices in African American cinema. Critic Travis Johnson reflects on the greatest African American film directors of all time, and picks their best work.

Having taken home Oscar glory with 2016’s Moonlight, Barry Jenkins returns to the big screen with If Beale Street Could Talk, an adaptation of James Baldwin’s acclaimed 1974 novel of the same name. It is a film that proves Jenkins is one of the most vital voices in African-American cinema today.

He joins a pantheon of vital African American filmmakers who are making waves in the screen space. We like to think that we’re living in a more enlightened age now and that audiences and critics are open to more diverse voices. However, the recent #oscarsowhite controversy demonstrates that the struggle continues.

Here are some of the finest African American auteurs, past and present, and their best work – beginning with Jenkins and If Beale Street Could Talk.

Barry Jenkins – If Beale Street Could Talk (2018)

Barry Jenkins’ second film Moonlight won the Academy Award for Best Picture, shattering a number of glass ceilings. It was the first queer-themed film to win the award, and the first with an all-black cast. Happily, we didn’t have to wait as long for his next film, If Beale Street Could Talk.

Set in 1970s New York City, the film follows the pregnant Tish (KiKi Lane) as she attempts to find evidence that her lover, Fonny (Stephan James) is innocent of the rape for which he has been arrested. He is, of course, but the legal system is not predisposed to treat impoverished young black men fairly. Around this, Jenkins weaves an incredibly detailed portrait of a family, a community, and a culture, precisely locating his tragic romance in its time and place. Beale Street is possessed of both a sharp sense of social realism and a yearning kind of romanticism. Lyrical, solemn, at times cynical but ever hopeful, it’s a masterful piece of cinema.

Melvin Van Peebles – Sweet Sweetback’ Baadasssss Song (1971)

The grand old multi-hyphenate of African-American cinema, Melvin Van Peebles can incontrovertibly claim to have launched the Blaxploitation film movement with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Van Peebles himself Is Sweetback, an orphan raised in a brothel who goes on the run from the law when he is arrested for a crime he didn’t commit, mixing it up with racist cops, black revolutionaries, biker gangs, and more along the way.

Narratively haphazard, Sweet Sweetback ticks from sex to violence like a metronome, and some of its excesses are eye-popping for a modern audience. But it’s formally audacious, brash, and at times leeringly in-your-face, capturing a mood of constant oppression countered by moments of explosive revolution.

Gordon Parks – Shaft (1971)

Well, you certainly know the song.

While Sweet Sweetback pulses with manic invention and wild style, Shaft is a far more smooth and polished affair, with its Isaac Hayes rhythms on the soundtrack, its leather-coated hero, and its take-no-shit attitude. Richard Roundtree is the hypermasculine private detective of the title, who finds himself in it up to his neck when hired by a Harlem crime boss to rescue his daughter, who has been kidnapped by the Mafia. Not that any of his opponents present much of a challenge – Shaft is so damn cool that he can overcome any obstacle by dint of sheer Shaftness.

Shaft was the second film from director Gordon Parks, who enjoyed a career as an acclaimed photojournalist from the 1940s to the 1960s before turning to cinema. His previous film, 1969’s The Learning Tree, saw him become the first African-American to write, produce and direct a film for a major studio. His varied career is littered with remarkable accomplishments.

John Singleton – Boyz n’ the Hood (1991)

When Boyz ‘n the Hood opened in the US, gang violence erupted in cinemas screening the film. On opening night alone, some 20 incidents saw 23 people injured by gunfire and one killed, as members of rival gangs found themselves lining up to check out John Singleton’s semi-autobiographical account of growing up in crime-wracked South Central Los Angeles. Responding to claims that his film provoked violence, debut director John Singleton, then 23, said, “I didn’t create the conditions under which people shoot each other. This happens because there’s a whole generation of people who are disenfranchised.”

Boyz n’ the Hood depicts such a generation with clarity and empathy, focusing on three friends as they struggle to survive the daily violence of the ‘hood, with gang member turned elder statesman barber Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne) on hand to dispense hard-won wisdom. Singleton went on to create other socially aware films such as Higher Learning and Rosewood before retreating into more commercial fare such as the 2000 remake of Shaft and 2002’s 2 Fast 2 Furious.

Spike Lee – Malcolm X (1992)

Spike Lee has been such an important cinematic voice for so long that it is almost unthinkable that he is only now enjoying his first Academy Award nomination for Best Director, thanks to the electrifying BlackKklansman. A stridently outspoken, politically motivated filmmaker, Lee made his feature debut in 1986 with the provocative sex comedy She’s Gotta Have It, but really made his bones with 1989’s landmark drama Do the Right Thing, a blistering look at racial tensions in contemporary Brooklyn.

However, it’s his 1992 biopic Malcolm X that is his most essential film. Starring frequent Lee collaborator Denzel Washington as the titular militant black leader, the film is a sprawling biography that trace’s X’s life and legacy from his early criminal years, to his conversion to Islam, his radicalisation, his assassination, and his current position as one of the most important and influential figures in African-American history.

Ava DuVernay – Selma (2014)

Unarguably the most high profile African-American woman filmmaker of the day, Ava DuVernay first came to prominence in documentary work, directing 2007’s Compton in C Minor and 2008’s This is the Life: How the West Was One, before moving into fiction features. However, it was Selma that really made the world sit up and take notice: an account of Martin Luther King’s (David Oyewolo) 1965 voters’ rights march from the titular Alabama town to the state capitol of Montgomery.

Selma is an extraordinary film. Although focusing tightly on one key event of both King’s life and the civil rights movement in general, it manages to speak volumes, casting a wide net over the politics, culture, and battles of the time.

Ryan Coogler – Creed (2015)

Yes, Black Panther is great, and yes, Black Panther is the first superhero movie to score a Best Picture Academy Award nomination. But the highlight in director Ryan Coogler’s three film oeuvre to date is undoubtedly his second offering, 2015’s Creed.

Expanding on Sylvester Stallone’s venerable Rocky franchise, Creed posits an heir to deceased heavyweight champion Apollo Creed in the form of Adonis “Donny” Creed, who wants to follow his father’s footsteps into the ring – and he wants the ageing Rocky to coach him. The familiar beats of a good Rocky movie are once again hit, but there’s an exciting new rhythm in this installment. It is a film that takes the franchise in a wholly new but appropriate direction, both dramatically and culturally.

Boots Riley – Sorry to Bother You (2018)

Can you call someone with only one film under their belt an auteur? If so, then surely rapper turned filmmaker Boots Riley makes the grade. Long in gestation, his debut feature Sorry to Bother You got an extremely limited release in Australia last year, but blew away pretty much every audience that managed to catch it.

Taking place in a surreal world that plays like a hip hop riff on Repo Man’s punk aesthetic, the film follows struggling Cassius “Cash” Green (Lakeith Stanfield) as he learns that the way forward in this fallen, hyper-capitalist world is to suppress his blackness and adopt a white voice for his telemarketing job. Sorry to Bother You is overstuffed with ideas to the point of explosion, but it has energy and flair to spare, which barely mask the righteous indignation at the core of its metaphorical urban fantasy world. There’s nothing else out there that’s quite like it.