Fugue states and death dreams: revisiting the late, great David Lynch

As we awake to the sad news that the great David Lynch (the greatest?) has passed away, we republish Aaron Yap’s reflections on the master filmmaker from 2015.

You can also read Dominic Corry’s interview with Lynch as Twin Peaks made an unexpected comeback and Luke Buckmaster’s retrospective on Wild at Heart as it turned 30.

As Lynch told us in Twin Peaks: “You know about death, that it’s just a change, not an end…”

The last time I saw a David Lynch film an uncanny thing happened—“Lynchian” I guess you could say. About 5 years ago, I held a 35mm screening of Blue Velvet at the Academy Cinemas to raise funds for my dad’s cancer treatment (still eternally grateful to everyone who helped make it happen!).

Everything went swimmingly—that was until a reel change, maybe just over halfway into the film, the image flipped, and suddenly we were watching Blue Velvet UPSIDE DOWN! And it wasn’t just flipped, the image was reversed, as was the soundtrack. 20 minutes of dead screen later, the film was back up and running as per norm, the sorcerous technical anomaly nowhere to be seen again for the remaining duration.

I guess this is kind of an unintentionally meta, real-life analog to the heart of Lynch’s work: those momentary fissures in reality that allow the surreal and the inexplicable to erupt to the surface. Like many budding film buffs growing up in the ’90s, I was drawn to these slippery qualities of his dark and beautiful universe.

Cinema’s enduring, consummate “weird guy”, Lynch transformed us into clue-hunting detectives obsessed with unlocking the key to his oneiric, impenetrable narratives. Sitting down with a Lynch film was a matter of entering a world, not passively watching a film to be entertained. It wasn’t always pretty or easy, but it held you there in a trance, unable to resist its hypnotic pull.

The funny thing is, once I’ve grown older, devoured more films and absorbed more experiences, those bizarre elements have become gradually muted. It’s not that his films are any less weird, it’s just that I’m less fixated on those head-scratching details—what’s in the Blue Box? where’s Agent Chester Desmond? who is the Mystery Man?—and more inclined to be emotionally engaged with the work in a direct, non-cerebral manner than I was as a young’un.

For the record, here’s where I stand on Lynch’s films at this stage: I rate Eraserhead up top. There’s a pure, ripped-from-the-Id rawness to that film that’s absolutely, and uniquely, timeless; if he never made another movie after that I don’t think I’d complain. Blue Velvet is a stone-cold masterpiece. I’m just cold on Wild at Heart. The jury is still out on Inland Empire (still yet to find three hours I can appropriately devote for a rewatch). I definitely have time for his “outlier”-type work like The Elephant Man, Dune and The Straight Story.

Fire Walk with Me, Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive: as a body of work, these three films, for my money, showcase Lynch at the height of his powers, easily comparable to say, Hitchcock’s stellar run from Vertigo to The Birds.

Seen in quick succession, there’s an interlocking neatness—in themes, visual motifs and characters—to this trio that’s attractive and satisfying. I love how they seemingly collapse into each other like one fluid extended dream. While Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire are usually lumped together as an “L.A. Trilogy”, I prefer assigning the trilogy reading to Fire Walk with Me, Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive as Lynch’s set of “psychogenic fugue” films. They’re all tighter, aesthetically cohesive than Inland, which, let’s face it, is a fucking hot mess.

Lynch first embraced the term—a mental disorder in which an individual suffers from memory loss and imagines another identity for themselves—during the making of Lost Highway, but FWWM had already been exploring similar psychological splintering and doublings of its characters, and not to mention, featured the sort of jarring bifurcate narrative that would perplex many viewers of Highway and Mulholland too. (note: spoilers follow)

In FWWM, Twin Peaks’ whodunit queen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) is seen as a high school sweetheart by day, a drug-snorting prostitute by night. Her dad Leland is possessed by and wrestling with the demonic, supernatural figure/alter ego Bob, who’s sexually abusing Laura. Halfway into Lost Highway, Lynch switches its protagonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a troubled jazz musician who’s arrested for the murder of his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette), for Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a mechanic who’s like a younger, cooler, more virile version of Fred.

Likewise, albeit inverted, Mulholland Drive’s fresh-faced, aspiring Hollywood starlet Betty (Naomi Watts) is generally interpreted as the idealised death-dream fantasy of the strung out, failed actress/jilted lover Diane Selwyn. And one doesn’t have to be a genius to find parallels between the blonde/brunette dynamic of Betty and Rita (Laura Elena Harring), Renee/Alice in Highway and Laura/Donna in FWWM (or Laura/Maddy in Twin Peaks). Bob, Mystery Man and The Cowboy? They’re all members of the same Sinister Guy Club.

Maybe more than any other weird Lynch film, FWWM is the one I’ve grown to respect and adore over the years. Considering the bad buzz that it weathered upon release—the Cannes booing, the subsequent critical drubbing, the disappointment of fans (even Tarantino swore off Lynch)—this prequel to Twin Peaks, retracing the final days of Laura Palmer’s life, is largely deserving of its underrated status.

The radical tone-shift, needless to say, polarised anyone who religiously tuned into the show. Although a recognisably quirky opening half and a host of returning cast members indicate that we’re in the same world of Peaks, it’s also quite clear that FWWM isn’t that world—it’s Laura’s, and it’s downbeat, confused, heart-breaking, relentlessly nightmarish, constantly on the brink of falling into the proverbial abyss.

Not to rob Lynch of his meticulous vision, but so much of FWWM is powered by the sheer ethereal presence of Sheryl Lee as Laura. We’ve come to know her as the plastic-wrapped corpse who whipped the TV world into a frenzy in 1990, so it’s something of a wonder—almost a privilege—to see her alive and breathing before our eyes.

Lee gathers an enormous amount of sympathy for the character—we’re bewitched by her in the way that her suitors like James or Bobby were—and her eventual departure, scored to Angelo Badalamenti’s transcendent theme, produces arguably the most moving, haunting, startlingly graceful ending—hell, sequence—of Lynch’s career thus far.

Faced with the hostile response towards FWWM, Lynch could’ve easily pandered to the mainstream for his next work, but being Lynch, devised a battier, more alienating thing called Lost Highway,. Co-written with Wild at Heart author Barry Gifford, this tenebrous neo-noir puzzle, in some ways, is the film you’d want to recommend when someone asks where to start with Lynch.

It boasts a narrative deviation that’s extreme and enigmatic even by his standards, and I still find the first 40 or so minutes some of the creepiest, druggiest shit Lynch has ever committed to film, a mesmerising lesson in unsettling an audience simply with a fuzzy video tape, shadowy corridors, a few pot plants and Robert Blake’s kabuki-fied face. This portion is so masterful and intensely charged, there’s a tendency for viewers to undervalue the Pete Dayton story, which, with its gangster’s moll/lovers-on-the-lam tropes, seems comparatively straightforward.

But the relative placidity shouldn’t be mistaken for a slackening of directorial grip. Here Lynch’s interrogation of male anxiety is just played in a different register: looser, freer—jazzier—a waking dream of bright L.A. exteriors and coital ecstasy tempered by Robert Loggia’s seething rage and slabs of Rammstein’s industrial grind. In the loopy, Mobius strip-like ending, Lost Highway suggests the impossibility of exit for this unhinged mind: Fred is trapped in a purgatory of his own making, destined to repeat the same nightmare all over again.

My relationship with Mulholland Drive is strangely minimal: though I dig it, I haven’t seen it since in its initial release in 2001. Revisiting it now however, especially alongside FWWM and Lost Highway, it’s even clearer that it represents Lynch’s dream logic filmmaking at its most refined and lucid.

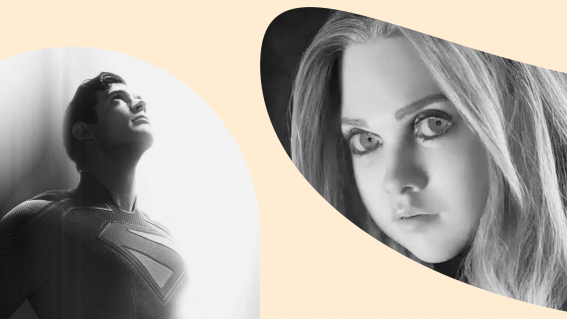

Mulholland Dr.

Perhaps that’s one of the reasons why, among all his weird films, it seems to hold the widest cross-over appeal. That, and maybe because it doesn’t involve incest, abuse or male insecurities, but is instead wired into our endless collective fascination with the glamour and artifice of Hollywood.

It’s Lynch’s Sunset Blvd., both profoundly affecting in its belief in the transport of performance (see Naomi Watts’ stunningly acted audition centrepiece, the Club Silencio sequence) and corrosively cynical in its confrontation of the industry’s rotten core (the behind-the-scenes puppeteering of moguls, the influence of drugs, money).

Mulholland’s final bug-out might be the easiest to decode of his films — a “meaning” of sorts can be found within the skillfully re-purposed clues if you wish to — but it’s just shy of a definitive answer. In true Lynch fashion, he grants us something even better: the opportunity to continue dreaming, long after the screen has faded to black.

Originally published by Flicks on Jan 20, 2015.