Happy 30th bday, Predator: you kicked arse in the 80s – and you’re even better now

First arriving in cinemas in mid-1987, director John McTiernan’s mud-splotched action SCI-FI classic Predator – a survival in the wilderness story with a bad arse extraterrestrial twist – is now thirty years old. To commemorate the film’s anniversary, screenings of it have appeared across the country, including sessions this week in Sydney and Melbourne and one next week in Adelaide.

Given Predator’s age now encapsulates a nice even number, with plenty of symbolic candles to extinguish (or destroy with submachine guns, followed by delivery of a zinger) more audiences will be treated to it on the big screen than usual, presumably some for the first time. It would be wrong, however, to suggest the film ever came close to disappearing from the zeitgeist.

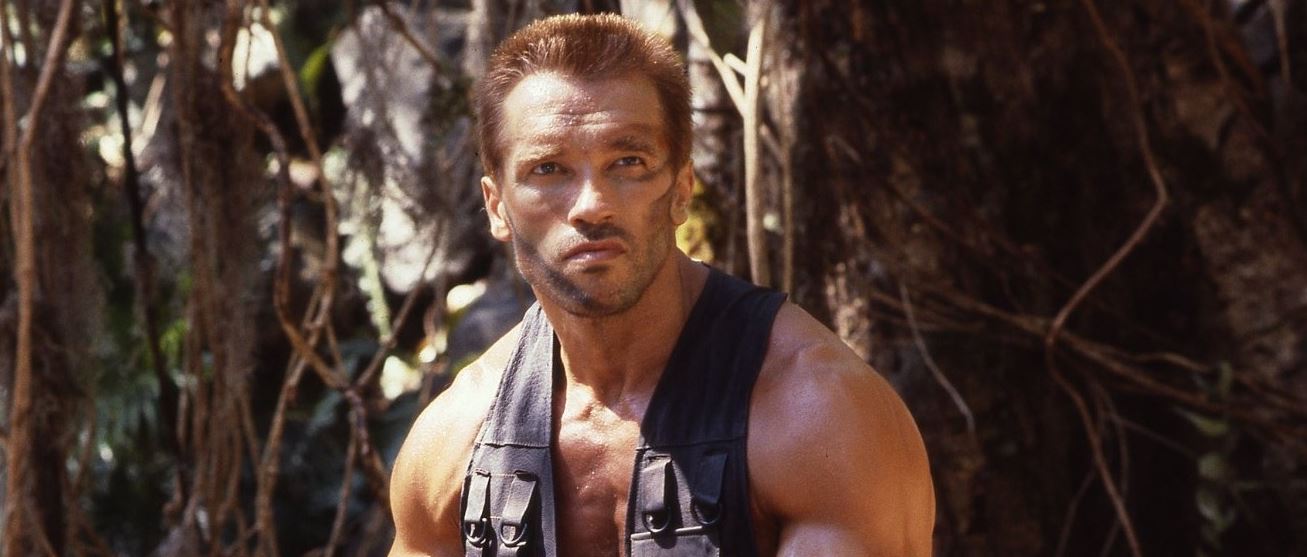

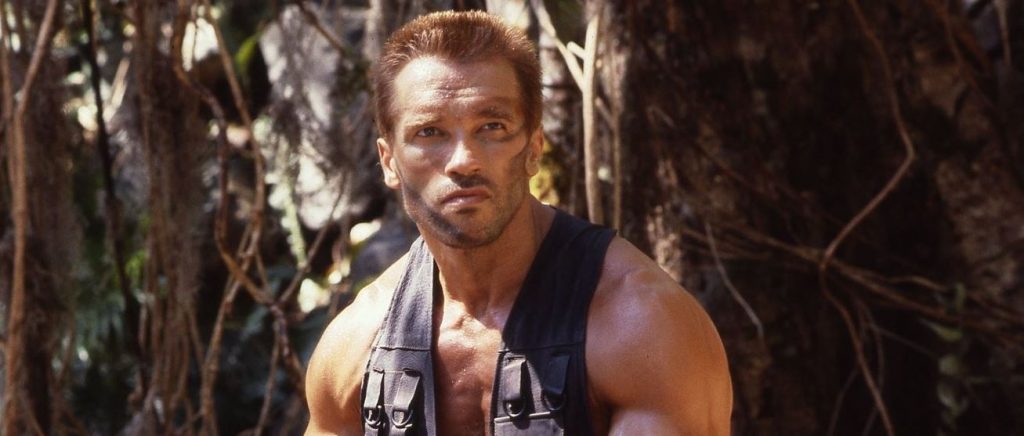

A handful of sequels and spin-offs arrived intermittently over the years, with another scheduled for 2018. Predator’s tally of pop cultures references keeps expanding. Superfans continue to dress up like rastafarian warriors from outer-space, and the film-savvy general public are still keen as mustard to sing the praises of vest-clad Dutch (Schwarzenegger) and his festy looking foe. Writers and commentators, such as myself, have barely needed an excuse to get to the chopper (pronounced “get to da chaaaaappaaaaahhhhh!”) and take the film for a spin once more, some declaring their love in no uncertain terms.

This is not a case of squinting through the haze of nostalgia and remembering the film to be better than it actually was. In many ways, in fact, as the syntax of action cinema has evolved – generally becoming faster and messier – the elements that make Predator not only a roaring piece of entertainment, but a great work of art, have become more pronounced with time. You don’t need to fondly remember this film; you need to see it again.

In May 2015, discussing his berserko pedal-to-the-metal chase flick Mad Max: Fury Road, director George Miller reflected on the fact that this film – which has the speed and throttle of a carnival ride – contains more than twice as many cuts as the second Mad Max movie, The Road Warrior. Miller concluded that “we’re speed-reading movies now.” His point is obvious: films today are faster paced.

The speed-reading analogy only really works if audiences are given more to consume, however, not the same amount of information (or less) chopped into smaller pieces. “Speed reading” appears to be a gentler way of saying: audiences get bored quicker. That may be so, but the controls are always in the filmmaker’s hands: fast forward buttons notwithstanding, it is the director who dictates the pace of a film, not the audience.

I doubt anybody, even younger crowds, will watch Predator on the big screen today and think: man, this needs to be sped up. Or: gee, this is slow. And yet it is constructed with a patience and poise we don’t see all that often in action movies anymore. At one point Jesse Ventura famously proclaims “I ain’t got time to bleed.” Neither does the film.

The character development (a credit to screenwriters Jim and John Thomas) is compact and muscular: these gritty, beefy people don’t mince words. When it’s time for them to die, McTiernan (who also directed Die Hard and The Hunt for Red October) doesn’t linger. He is more interested in environment than human details, assisted in no small measure by superb cinematography from Don McAlpine – the great Australian veteran, who recently shot Ali’s Wedding and The Dressmaker.

The explosions and zingers are fun (“Knock knock,” Dutch says, just after kicking a door down and just before opening fire). But Predator’s greatest achievement is atmospheric. You feel like you’re in the jungle, jumping at shadows with these godforsaken, woebegone rednecks. Like the recent, Liam Neeson-led survival drama The Grey, McTiernan feeds the concept of the alpha male to the wolves. Flex those muscles all you like, and clutch that gun as tight as you want, pal, the director appears to be saying: it’s not going to help when you’re out-monstered by Mother Nature.

Unless, of course, your name is Arnold Schwarzenegger. Dutch achieves victory in the end, though it is hard-earned and requires a reasonable amount of brain power. Our hero discovers his “ugly motherfucker” of an opponent cannot see him when he is covered in mud, and plans accordingly. The film’s prolonged, cat-and-mouse, mano a mano showdown between Dutch and the Predator feels a little like Survivor gone very wrong – moreo so upon Dutch’s realisation that the alien is not hunting for food, but for entertainment.

The final act is also, with the exception of Arnie grumbling a few things to himself, dialogue-free. That’s a bold move: the director introducing an essentially silent film at a point in the drama where everything needs to come to a head (and, of course, to climax spectacularly). If Predator wasn’t so proficient tonally, we might have spent this time (about thirty minutes) missing the one-liners and extraneous supporting cast members. We don’t.

So when we blow out the birthday candles for Predator – or demolish them with high-powered weapons, metaphorically speaking – we do so understanding that it was a fine film when it was first released in 1987. And it’s even better now.