Hey Hollywood, can we take a break from hitman movies?

Knox Goes Away is the latest in an endless supply of hitman movies that insist their protagonists are special. Luke Buckmaster surveys the genre and says: please, please, no more.

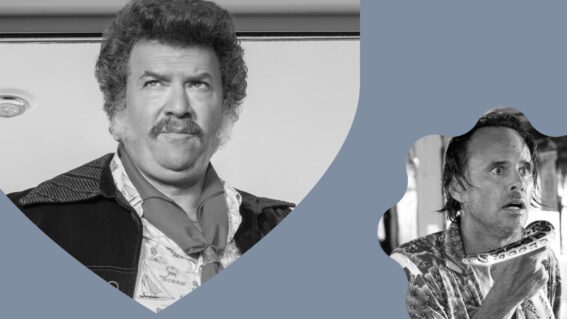

Knox Goes Away (Assassin's Plan)

The eponymous protagonist in Knox Goes Away, played with downbeat charm by Michael Keaton, isn’t your average hitman. The film stresses that he’s a deep-thinker, a real intellectual. In its first dialogue scene, which takes place at a diner, Knox brings with him some light reading: Wilfrid Sellars’ Empiricism and the Philosophy of the Mind. Fellow hitman Muncie (Ray McKinnon) makes a comment about how he owns “ten thousand books”; later, when Knox’s name is mentioned in a cop shop, a detective says this guy is clearly smart because he has two PHDs—on English literature and American history.

The other factor that distinguishes Knox from run-of-the-mill killers is that he suffers from early onset of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare dementia-inducing brain disorder. His mind will soon become a great big black hole. This adds a fleck of novelty to a reasonably stylish, competently staged film that nevertheless feels very “so what?” Particularly for those who’ve seen 2022’s Memory, in which Liam Neeson also plays a dementia-afflicted killer-for-hire.

Hitman movies are always insisting that their protagonists are special. This can manifest as a form of ultra strict professionalism, like Tom Cruise in Collateral and Nic Cage in Bangkok Dangerous. Sometimes they’re special because they’re ex-government agents, thus extremely dangerous—like in The Equalizer. Sometimes they “have a heart,” taking sympathy on innocents (Chow Yun-fat in The Killer) or becoming a father-like figure to an apprentice (Jean Reno in Léon: The Professional). In at least one instance they’re special because they really love their dog (John Wick); they can even be genetically modified (Hitman: Agent 47).

Sometimes movie hitmen are special because they kill time travelers (Looper) and sometimes because they while away the day gasbagging about matters unrelated to the job (like Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta in Pulp Fiction, and Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson in In Bruges). Sometimes they’re special because they only kill people who try to hire them (Mr. Right). Sometimes they’re not really special, but old clothes and ravishing period details make them seem special (Road to Perdition). Sometimes they’re special because they’re cultured, like Knox, and can quote Dylan Thomas (Michael Fassbender in The Killer).

I could go on. The “special hitman” canon reached its natural endpoint this year, when Richard Linklater’s Hit Man declared its protagonist special because he is in fact not a hitman at all. Given the nauseous amount of hitman movies that’ve come our way, often delivered with only slight variations, could we please, Hollywood, call a moratorium and take a break from them?

The answer, of course, is no: Knox may go away, but hitman movies won’t. Good ones will continue to be few and far between. Partly because filmmakers find themselves boxed in by vulgar ideologies; remember, “hitman” is another way of saying “serial killer.” Offering a redemptive arc poses all sorts of problems. And dryly capturing professional killers going about their business, while perhaps morbidly interesting, is hardly emotionally gratifying. Thus the need to make them special.

The truth is, despite the ancient mystique associated with this line of work, there’s nothing special about it. In contrast to assassins, who tend to be ideologically driven, hitmen are in it for the bucks—the cold-hard cash. They are a feature and inevitability of capitalism.

This is rarely anything close to a central theme. The film that springs to my mind as an exception is Andrew Dominik’s Killing Them Softly, starring Brad Pitt as hitman Jackie Cogan, who sees his job as means to balance the books. “This is not a country, this is a business,” he says, the film using his work, and gangsterism more broadly, as a metaphor for the dangers of free enterprise in unregulated economies.

Cogan likes to kill his clients from a distance, unemotionally. He wants to kill them softly—like politicians who pass laws that send people to their graves. This is a rare example of the oomph hitman narratives can have when they’re smart and thematically interesting—and yet, the “hitman is special” trope reigns supreme. Has somebody made a movie yet about a hitman with tourette’s syndrome, or narcolepsy, or hoplophobia (fear of guns)? It’s just a matter of time.