History and True Stories Might Be Holding the Bechdel Test Back

At school, I was great with numbers and terrible with words. Somewhere between then and now, I ate a big bowl of irony and became a writer. That makes about as much sense as a unicycle wheelchair, but I’ve never been a balanced person, so in its own absurd way, it makes complete sense – just like how a negative multiplied by a negative equals a positive.

See? Maths. I can still do it.

But I haven’t done much maths-ing in a while, and I’m only bringing this up because I’ve had a theory surrounding recent films and the Bechdel Test that requires some number-crunching.

Theory: Films that are not based on true stories are more likely to pass the Bechdel Test

I grew curious about this ever since this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Picture were announced. Half of them passed the test (Brooklyn, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Martian and Room) and half of them failed (The Big Short, Bridge of Spies, The Revenant and Spotlight). The ratio of Oscar films passing the test isn’t exactly surprising (or encouraging), but while these two groups are split by their test results, another thing separates them: only the failed films are based on real events.

It could just be a coincidence, of course. However, I have a shifty-eyed suspicion that, in the field of true stories recorded for the history books, the vast majority of the subject matter would have either been about a men in male-dominated areas (like soldiers in World War II, whalers in the 1800s, thunder-douche stockbrokers in 2008) or stories skewered by the men who “wrote” said history books. If this were the case, this could suggest that the conversation about how women are represented in films needs a bit more focus on how we tackle films based on truth and history.

The results

Just like the Bechdel Test itself, my own little research is far from perfect and should not be treated as a metric. For one, I did not get a research grant for this, so I didn’t run through EVERY SINGLE FILM released in 2015 – no docos, hardly any foreign language films, just big releases.

I also took many of the films I gathered from the Bechdel Test website, which also missed a number of releases (why would anyone ignore the emotional tour-de-force that was Hitman: Agent 47?). I added some other films I saw that year, just because I felt it necessary, and labelled each entry to the best of my abilities (you might argue that Minions isn’t considered ‘Original’, and fair enough).

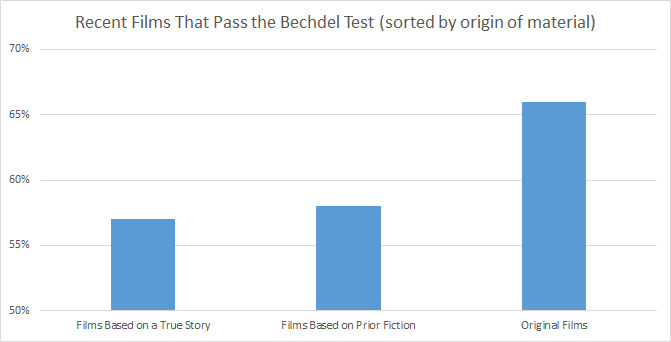

In that document sample, 70 out of 114 films passed the test (61%). After a few minutes doing some boring Excel stuff, I produced a graph that aligns with my first theory…

The number of ‘original’ films that pass is 5% higher than the average of the whole sample, with ‘true stories’ dipping 4% lower. In order to round the results out completely, I added adaptations from ‘prior fiction’, which wasn’t much higher than ‘true stories’.

The salient difference here is that roughly 14.5% more ‘original’ films pass the test than ‘true story’ films.

It’s worth noting that the number of ‘original films’ were more than double ‘true stories’, but roughly the same as ‘true story’ and ‘prior fiction’ combined.

The moral of the story

Theoretically speaking, every film should pass the Bechdel Test. Thus, all three categories should aim for a 100% pass mark. But I disagree with that, for that would imply a stern creative limitation to the stories that can be told for reasons that go out of the field of female representation. (All is Lost, for example, is a dialogue-free thriller starring one person, so that could never pass the test based solely on the number of characters the filmmaker chose to have in the film.)

Continuing to treat the test like a stern metric risks diluting its original intention. The Mary Sue said it best when talking about Star Wars: The Force Awakens, stating “that test is the product of desperation; a product of never seeing women’s stories told at all, of seeing women only existing in films to serve the stories of men.”

Despite not being perfect, the Bechdel Test is certainly a useful tool to giving us a heads-up on the issue – we just don’t know what the percentage sweet-spot is yet. (I think ‘achieving a number’ is beside the point.) But from what the results reflect, it appears that ‘true stories’ and ‘prior fiction’ films are falling behind.

The three take-home points

Perhaps there needs to be a bigger cry for women’s history to be represented on-screen, or at least parts of history that aren’t so male dominated. Admittedly, as previously mentioned, such stories would require more digging through the male-written archives. But even the most renowned historical achievements for and by women have seemingly taken an age to get made. How weird is it that Suffragette, a film about the activists who fought for women’s right to vote, only just came out?

Perhaps the microscope needs to be pointed at the fiction being adapted to screen. Better yet, maybe that fiction can be creatively modified in a way that expands women’s roles without taking away from the intention of the material.

Perhaps (and this one’s my favourite) we just need more original films.