How Incantation perfects the visceral horrors of found footage

Taiwanese terrifier Incantation might not have shown up on your Netflix homepage yet, but it’s absolutely worth a watch—for found footage fans and skeptics alike. Eliza Janssen hones in on the memetic, infectious qualities of its genre.

Hou-ho-xiu-yi, si-sei-wu-ma. Hou-ho-xiu-yi, si-sei-wu-ma. If you’re not one of 929 million people in the world who can speak Mandarin, don’t sweat it: your brain will latch onto the accursed titular Incantation of Kevin Ko’s found footage horror after only a few repetitions. Unfortunately.

A genre which uses a kind of diegetic kayfabe to make viewers believe, even if only momentarily, that they’re watching documentary moments of horror, found footage is having a bit of a critical renaissance. Early films such as indie-to-mainstream success The Blair Witch Project and the still-horrifying UK TV movie Ghostwatch were so unprecedented that they sparked concerns about the actor’s convincing onscreen deaths (the BBC was forced to apologise for screening the latter after countless traumatised viewers wrote in to complain).

Since then, the cheapness and repetitive “and they were never seen again” scares of Paranormal Activity and its imitators dampened the genre’s appeal. I reckon since the shift to (ugh) “elevated horror”, though, audiences looking for a scare are again craving the rawness and ingenuity that found footage can inspire. It’s a genre that welcomes low-budget filmmaking, with the Unfriended franchise and arthouse gem We’re All Going To The World’s Fair also relishing modern ideas of virality and the toxic medium of the internet.

Some of my absolute fave found footage films, Lake Mungo and Noroi: The Curse, create a gut-deep dread for the characters that can be difficult for more obviously stylised and fictional horror to achieve. The realism of candid moments and raw cinematography means we worry more intensely for the film’s characters—and I haven’t longed for a horror movie victim to make it out okay quite so much as I did while watching Incantation.

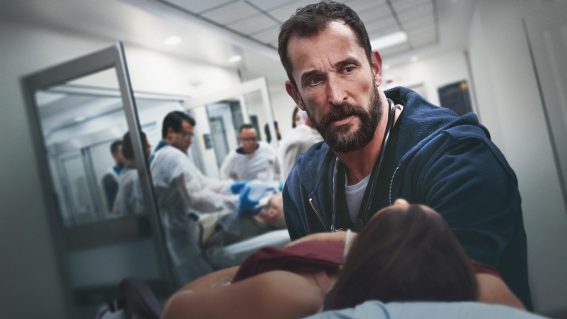

Tsai Hsuan-yen plays Li Ronan, a fragile Taiwanese single mum eager to make her home a welcoming space for her daughter Dodo (insanely cute Huang Sin-ting). This woman will do literally anything to keep her kid safe from the unexplainable circumstances that brought child services into the picture some months ago. Tragically and brilliantly, as Incantation progresses we simultaneously believe that Ronan is both a terrific parent, and that Dodo’s foster care organisation is absolutely in the right to suspect otherwise.

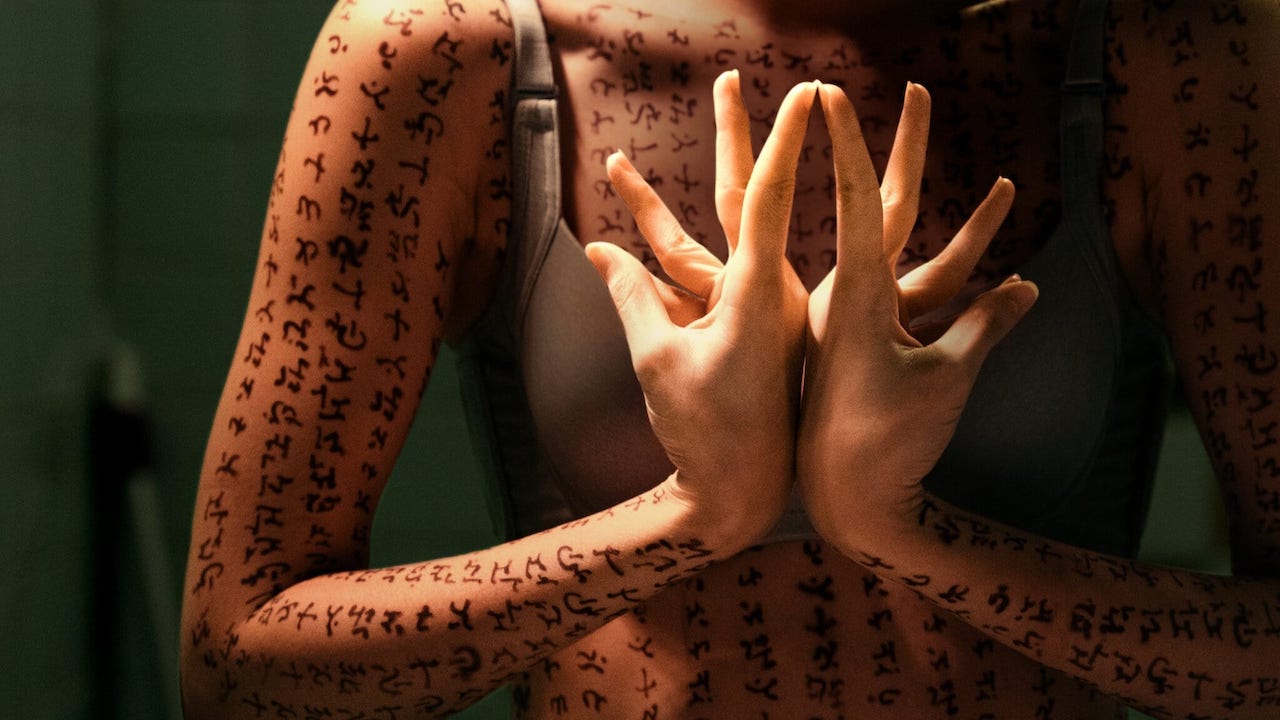

Because Ronan used to be a “ghostbuster”, and she’s still haunted by her vlogging squad’s visit to a remote Chen clan village six years ago. Like in Noroi, the horror here is based in obscure regional superstitions of a small mountain community, but Ko creates a fictional deity to allow for the film’s mystic hand signals, symbols, and rituals.

After Ronan’s boyfriend and colleague break a few too many of the fringe religion’s taboos for clout, they enter the Tunnel Which You Must Not Enter (you guysss!), the footage of their last remaining moments is lost, and she is left alone to raise a child bearing a curse which proves contagious to those around her.

Ko also writes and edits the film, and whilst sometimes it can be difficult to parse the chronological timeline of events, the pace of Ronan’s non-linear unfolding nightmare never yields. The most impactful scenes have a video-game-esque quality, a weak phone flashlight sweeping around the room to zoom in on a flailing caterpillar or a Buddha statue that was totally facing the other way a few seconds ago. Enjoyably, there’s not too much of the obstructive shaky-cam we get in lazier found footage entries—just an atmosphere of oppressive terror.

In the film’s opening scenes, when we still don’t understand what’s haunting Ronan or why she doesn’t have custody of her daughter, she shows us two optical illusion GIFs: of a Ferris wheel and of a subway train. With our mental will, she tells us, we can reverse the original direction in which we see the GIF moving. Seasoned horror viewers will already be getting nervous: we’re about to see some shit that we will, the film informs us, be unable to un-see.

Later, English text and Mandarin Pinyin translate the flickering characters of the Chen spiritual chant. The words—and Ronan’s tearful pleas to camera—ask us to join in, and give our name to the film. “You don’t even have to say it loud”, she tempts us. It’s like telling somebody not to think of a black dog, whatever they do: the brain is a fickle little pink lump, and I dare any viewer to not mentally blurt out their name to the screen before their super-ego can protectively step in.

Horror freaks with an awareness of internet creepypasta and the SCP fiction forums in particular may have come across the concept of “cognitohazards” and “infohazards”—images or text that supernaturally threaten those who merely see or comprehend them. It’s a tantalising idea, especially for a genre where, like Blair Witch‘s protagonist Heather, we often find ourselves too scared to look and to look away all at once.

You might find the trope of memetic terror a little tired, after Ringu and The Ring made popular the concept of cinema about cursed cinema itself being cursed. But combined with Tsai Hsuan-yen’s desperate, Babadook-esque maternal performance, Incantation builds a disturbing and potent story. At first we might feel furious at the villagers for their harmful superstitions (or at the film for exposing its central cognitohazard to us!), but once Dodo is at threat we’re forced to question what we would do to protect our loved ones from dark and unknowable forces.

Buttressing the movie’s high stakes of child endangerment and neglect, Ronan must starve Dodo in the film’s third act, under orders from a healer trying to exorcise the curse. What’s morally worse, watching your child suffer for their survival in the long-term, knowing their body might die before the demon does? Or simply inflicting that pain outwards to some poor suckers with a Netflix subscription?

Incantation is the highest-grossing Taiwanese horror movie of all time, and has already been called “the most terrifying film ever made”, which is probably a bit rich. But it’s definitely the scariest film I’ve seen in a while, and more importantly the scariest experience—drawing viewers in with simple yet unavoidable tactics of participation, paired with our empathy for the mother-daughter story.

Frankly I’m fine with taking on Dodo’s curse at this point, after seeing all the shit her poor mum had to go through, and considering how much Ko’s visceral filmmaking style affected me. Come on dude, read the end of the article along with me in your mind. You don’t even have to say it out loud: Hou-ho-xiu-yi, si-sei-wu-ma, hou-ho-xiu-yi, si-sei-wu-ma…