How soon is too soon? The fallacy of British TV satirising painful recent events

The latest in a questionable string of series aiming to wring laughs from recent UK history without any striking political commentary, This England feels like dramatisation for dramatisation’s sake to Lillian Crawford. Here’s where the trend goes wrong.

Good satire needs its finger permanently pressed to the pulse of politics. It is a responsive form of comedy, one which makes mockery of current events. It is often said that series such as Armando Ianucci’s The Thick of It could not be made today because the reality of contemporary politics is too outlandish and absurd to be satirised. A man as corrupt and unbound to rules and precedent as Boris Johnson, for example, can only be presented as he actually is to warrant laughter—a parody of himself.

The premise of This England, a six-part series written by Michael Winterbottom and Kieron Quirke, is simply that—to invite raucous guffaws at the previous British Prime Minister through brute presentation. The series poses a number of questions about the nature of dramatisation of real, recent events and the ethics of doing so, especially when so many people died during the COVID-19 pandemic.

If there is a finger of blame, it is at Johnson’s buffoonery. His endless quotations of “Winston” (Churchill, that is) and Shakespearean monarchs create a public envisioning of Johnson’s private life while seldom daring to push beyond such a superficial interpretation.

This is surprising considering Winterbottom’s background in satire, recently having directed Greed, which parodied the lavish lifestyle and absence of morals in business tycoons like Philip Green. Beyond some fantastical dream sequences riffing on real comments Johnson has made about women (“hot totty”) and gay men (“tank-topped bumboys”) among his other prejudices, Winterbottom rarely strays from straightforwardly scripting the development of the pandemic since 2020.

Much of this involves blending news footage with the dramatic scenes, creating an extended docudrama. It begs the question of why there was such an urgent need for This England to exist.

Posterity is the clearest reason—creating a fictionalised version of events immediately after they have actually happened for fear of collective memory loss or change. It is a niche genre attempted several times over the past decade. Two of the most notable examples are the screenplays of playwright James Graham, who penned both Coalition (2015) and Brexit: The Uncivil War (2019). Like Winterbottom and Quirke, both of these films are fairly straight-faced retellings of recent political history with a claim to authenticity in the staging of what politicians get up to behind the curtain.

It is a fallacious endeavour, given that these writers have no access to retrospective sources that would make good the claim of truth. It is a creative ‘filling in the blanks’ which the public are generally capable of doing themselves and sometimes better than the screenwriters.

Part of the appeal of these television films are the imitative performances of politicians. Coalition starred Bertie Carvel as Nick Clegg, Ian Grieve as Gordon Brown, and Mark Dexter as David Cameron as they navigated the shift in power away from New Labour during the 2010 general election. The film was broadcast at the end of the coalition government led by Liberal Democrat Clegg and Conservative Cameron, a reflective exercise in the extent to which these opposing parties had been able to work together to lead Britain.

Graham’s next film, Brexit: The Uncivil War, sold itself as an insight into the inner machinations of the Vote Leave campaign which won the 2016 referendum to remove the United Kingdom from the European Union. The film centred on Campaign Director Dominic Cummings, sold as the ‘mastermind’ behind the operation and portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch.

His casting drew explicit parallels between the film’s characterisation of Cummings and Cumberbatch’s modern portrayal of Sherlock Holmes in BBC’s Sherlock as a sociopathic (or at least socially awkward) genius, similarly used to represent Alan Turing in 2014 biopic The Imitation Game.

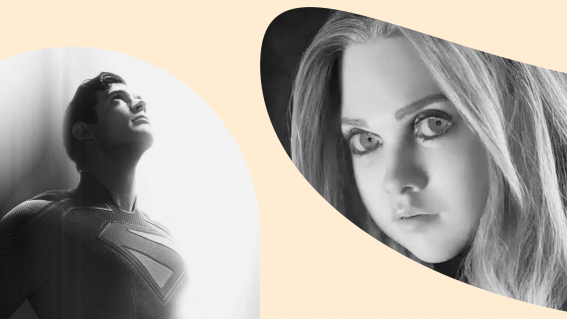

These films become ground for impersonation, but without any satirical edge to their writing, it’s unclear what purpose those impressions serve. This England stars Kenneth Branagh as Johnson, heavily made up in prosthetics to make him hunched, fat, and generally weather-beaten. The result is a characterisation akin to Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III, and Branagh brings his experience playing many of the Bard’s characters on stage and screen to the portrayal.

Devoid of political commentary or clear agenda, there’s an open question about the purpose behind Branagh’s perfection of Johnson’s mannerisms, voice, and appearance. It is acting for the sake of acting alone.

To create a series or a film about a tragedy by which hundreds of thousands of people in the UK lost their lives without justification is deeply uncomfortable. If the aim is posterity and preservation, then producing documentaries and commentary will be useful rather than merely dramatising events in a pretence to authentic portrayal.

Dramas like This England follow in a recent trend to impress through prosthetics alone, substituting for performance by showcasing the abilities of hair and make-up teams to recreate a person as though they were a waxwork. Then one has to ask who the real dummy is—Johnson, or us?