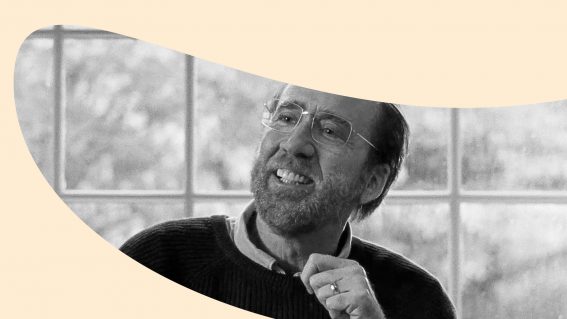

How the insidiously good James Wan went from povo indie artist to horror stalwart

Coming from humble origins, James Wan transformed into a mover and shaker for the horror genre—pumping out popular and often acclaimed titles. David Michael Brown charts his journey from shoestring budgets to blockbuster success.

When a screaming but determined Cary Elwes cut off his foot with a rusty hacksaw, the horror genre welcomed an extreme new talent into its bloody fold. Inspiring the much-maligned torture porn genre and spawning numerous sequels and reboots, Saw became a bloody calling card for James Wan, the franchise machine behind the Insidious and The Conjuring series—and also the director of his characteristically gnarly new movie Maligant.

Born in Malaysia, Wan emigrated to Perth at a young age and went on to study at Melbourne’s RMIT University. He, and his partner-in-crime Leigh Whannell, wanted to make a film after they finished film school. But with nothing resembling a budget, they could only afford to shoot in one location. With that restriction in mind, the embryonic script that was to become Saw was born. But how did two fledgling filmmakers, fresh out of university, raise the US$1.2 million needed to make their twisted concepts flesh and celluloid?

How Wan raised the cash to make Saw

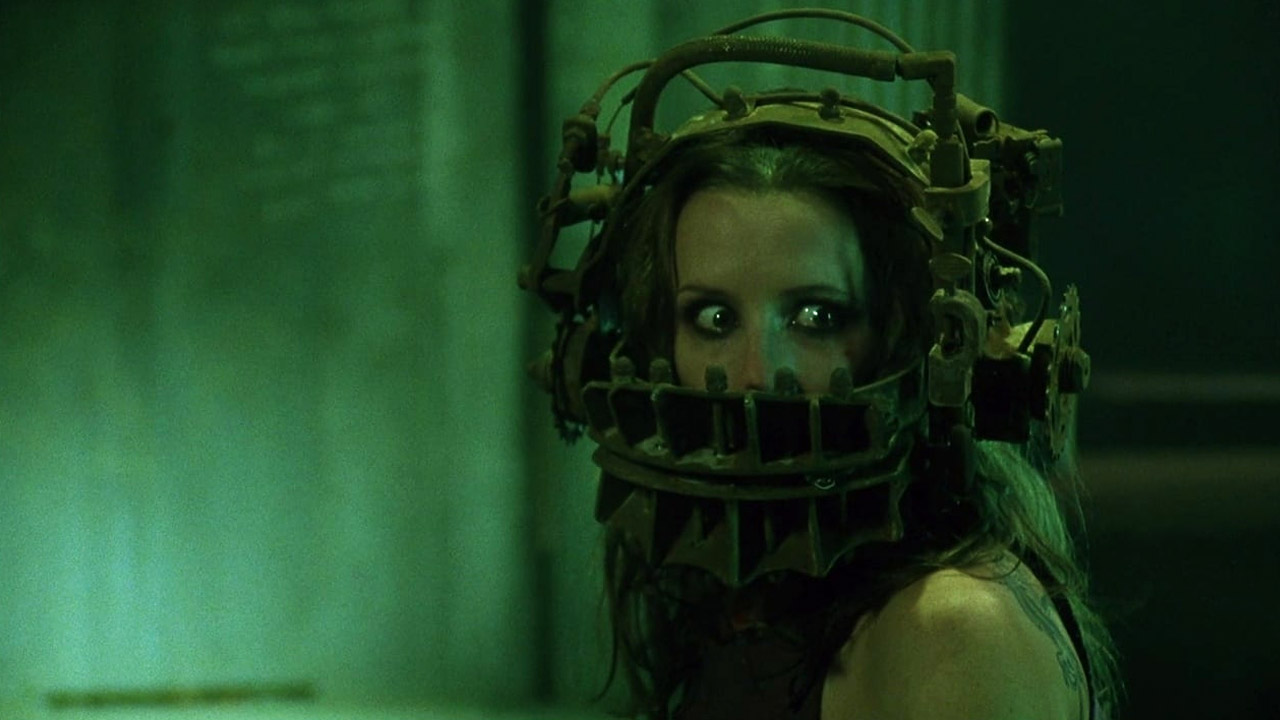

Raised on the likes of The Exorcist, Jaws and Poltergeist, the pair took a bloody leaf from Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead copybook (Raimi made a gore-soaked short, Within the Woods, to show to potential investors) and tested the water with a short film in 2003. Showcasing Jigsaw’s demonic puppet riding a tricycle, the brutal reverse bear trap, a key in an unconscious victim’s stomach and the same claustrophobic intensity and cruel trappings that would go on to make the feature such a success, the Saw short showed what Wan could do with minuscule funds.

What he did with just over a million bucks was make one of the biggest profit-making indie horror hits of all time, with Saw joining the ranks of Halloween, Paranormal Activity and The Blair Witch Project.

“The whole thing started in our bedroom, where I designed the doll,” Wan explained to Collider. “And the first film almost feels homemade. Which actually, to dovetail slightly, is what Leigh and I wanted when we went off to make Insidious, that homemade freedom and quality you get with Saw. There’s something very cool about that indie spirit that I try to hang on to even now with the bigger films that I’m working on.”

Then, Hollywood beckoned

With that kind of return, it wasn’t long before Hollywood beckoned. Saw sequels followed. Wan acted as executive producer on Saw II and Saw III, which he also wrote. The films continued the original’s success, albeit on a larger budget. Wan stepped behind the camera again for 2007’s Dead Silence, written by Whannell and starring True Blood’s Ryan Kwanten as a young widower returning to his hometown to search for answers to his wife’s death.

Wan’s vigilante actioner Death Sentence, loosely based on the 1975 novel of the same name by Brian Garfield, was also released that year. Kevin Bacon took the lead role as a man avenging the death of his son, only to find himself at war with the killer’s older brother (Garrett Hedlund). Both films saw Wan working with a US$20million budget, but both failed to scare up much box office interest.

Insidious returned Wan to his roots with a budget barely more than that of the original Saw, and continued Wan’s working relationship with Whannell (repeating the pair’s winning writer/director partnership). Insidious also introduced the filmmaker to Patrick Wilson, who would later appear in The Conjuring films and Aquaman. Wan joked to Den of Geek: “you know how Johnny Depp was to Tim Burton, Patrick Wilson is my Johnny Depp.”

The man with the Midas touch

Wilson and Rose Byrne play a couple dealing with strange supernatural occurrences after they bring home their son (Ty Simpkins) who has mysteriously slipped into a coma. Full of dark shadowy jump scares, a demon who looks like Darth Maul on steroids and a sense of dread that infiltrates every frame of the film, Wan also helmed the sequel, while Whannell made his directorial debut on the threequel. All three made a considerable profit compared to their budgets, proving, once again that Wan had the Midas touch. Whannell went on to direct two films back in Australia, Upgrade in 2018 and The Invisible Man in 2020.

Wilson joined Vera Farmiga, playing Ed and Lorraine Warren in The Conjuring. The Warrens were the real-life paranormal investigators who found fame after their involvement in the case that inspired The Amityville Horror, starring James Brolin and Margot Kidder. The first film in the franchise, set in 1971, saw the Warrens travel to Rhode Island to investigate the increasingly disturbing events that were making the lives of the Perron family a living hell. In the second, the spooky sleuths arrive in the United Kingdom circa 1977 to help the Hodgson family, who are being haunted by what became known as the Enfield poltergeist.

Both films made over US$300million internationally. A sequel and three spin-offs—The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It, Annabelle, Annabelle Comes Home and The Nun—followed, all produced by Wan.

A return to his roots

And now—after two sojourns into blockbuster land with Fast & Furious 7 and Aquaman—he has returned to the genre in which he made his name with Malignant. It’s Wan’s blood-written love letter to the garish ultra-violent Italian Giallo thrillers of the ‘70s and the Hitchcockian whodunnits of Brian De Palma, such as Dressed to Kill and Raising Cain.

“It’s horror, but it’s also a traditional thriller. It’s psychological, it’s serial killer, but it’s also potentially a monster movie,” he told Slash Film.

If there’s one thing that horror’s golden boy has proved over all these years, it’s that he knows how to scare people. And from the moment that the two bewildered and confused men awoke with a dead body in a strange room in Saw, to the blood-soaked frenzy of his most recent chiller, the adopted Aussie director has done just that. Insidiously; his thrifty aesthetic shining through. Proof, if needed, that you can’t keep an indie filmmaker down—you just have to give them more money.