I ain’t like that no more: is it time for Clint Eastwood to hang up his directorial guns?

Clint Eastwood’s new film The Mule arrives in cinemas this week. But his best years as a filmmaker are well and truly behind him, says critic Travis Johnson, who thinks the Hollywood legend might want to call it a day.

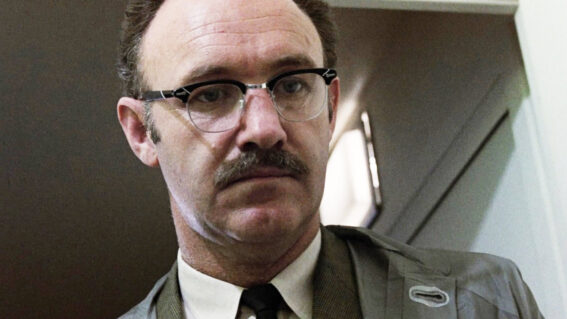

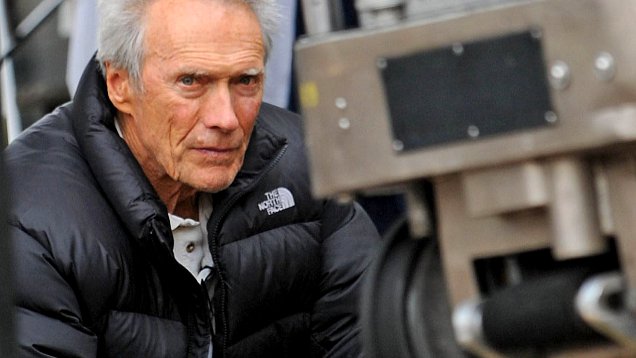

It’s a truth universally acknowledged – or at least a piece of received wisdom rarely questioned – that Clint Eastwood is a great director. Starting with his 1971 filmmaking debut, the thriller Play Misty For Me, he quietly honed his craft over subsequent projects, developing an unfussy, classical style that fits his laconic screen persona and his preferred genres like a glove. Clint’s a man’s man, of course, and he makes men’s movies – but generally with a restraint and artistry that stands in stark contrast to the overblown machismo prevalent in the action cinema of the ‘80s, the decade when he really earned his directorial bones.

If you wanted to, you could call him an artist, but one of that peculiarly American and masculine stripe, like Jackson Pollock and Ernest Hemingway. When he took home both Best Director and Best Picture for 1992’s Unforgiven, it seemed like both an acknowledgement of craft and admission to the A list: while an unarguably successful actor and director, Eastwood had long been something of a punchline for certain critics, with his minimalist style and popular genre roots making him easy fodder for arch bon mots. Now, with two Academy Awards under his belt, he was respectable.

Do you think, perhaps, he squandered it?

Even typing that feels heretical. Eastwood is not just a man, not just an artist, he’s an institution. He’s Dirty Harry, The Man with No Name, Gunny Highway, Philo Beddoe, and a couple dozen more besides. A real man and a great filmmaker – you can set your watch by that.

But, really, can you?

If we’re being real here – and the myth of Clint Eastwood demands we are – as a director, Eastwood’s great films are few in number, and his stinkers are legion. He’s a wildly inconsistent director. Like The Outlaw Josey Wales? How about Hereafter? For every Million Dollar Baby, there’s a Changeling. White Hunter, Black Heart (one of Eastwood’s best films, by the way)? Clint made noted turkey The Rookie the exact same year.

But let’s put aside the train wrecks for the moment, and grapple with this painful truth: most of Eastwood’s films are just mediocre. Over the course of his later filmmaking career, Eastwood has consistently produced the kind of films your dad falls asleep to on Sunday afternoon: middling dramas and thrillers with solid casts and just enough suspense to keep you paying attention, as long as you’re not too sleepy after a heavy lunch. Absolute Power, Blood Work, Space Cowboys, Gran Torino (a cut above, that one, granted), Invictus, J. Edgar…

All those films, you’ve doubtless already noted, were produced after the Unforgiven Oscar wins. They’re not the work of a capital A Artist at the top of his game, but of a journeyman. Quite frankly, anyone could have directed those films to as good or better effect (the same could be said of Sully, the last film that made people think Eastwood had perhaps arrested his slide).

Not to disparage his age – we should all be so vibrant when the odometer hits 88 – but his earlier work, though less polished, was better. Eastwood’s directorial offerings from the ‘70s and ‘80s were idiosyncratic, and that left-of-centre approach gave them a vitality his later output is sorely lacking. It’s difficult to imagine post-Oscar Clint creating something as eccentric as Bronco Billy, or something as dark and challenging as High Plains Drifter. Even his more by the book stuff, such as Sudden Impact and Heartbreak Ridge, are muscular, insistent works. Compared to these, his later films feel exhausted. The only thing they insist on is the television being turned down.

The thing is, it’s getting worse.

For the past several years now, Eastwood’s films have felt like indulgences – he gets to make them because of who he is and who he has been. Looking at the embarrassment that was last year’s The 15:17 to Paris, it’s hard to imagine Warner Bros, his longtime studio home, getting behind his most recent effort, The Mule, for any other reason. 2010’s misguided supernatural drama Hereafter is probably the turning point – after that you get soulless biopic J. Edgar, soulless musical biopic Jersey Boys, and, er, soulless jingoistic biopic American Sniper, which is not only a bad film, it completely mischaracterized its main subject to suit its thematic and political aims. But that’s a long rant for another time.

Meanwhile, there’s The Mule – another biopic that may or may not be in possession of a soul. While the film is currently sitting at a healthy but unspectacular 66% on Rotten Tomatoes, some critics have taken exception to its politics, with Leigh Monson of Birth.Movies.Death saying it revels in its “delusions of absolute moral certitude” while Flicks’ own Adam Fresco accused it of being reliant solely on the fading charisma of its star.”

Look, there’s no doubt that Clint Eastwood has made some truly excellent films. The question is whether, in judging someone’s career, their batting average matters. Yes, we got The Outlaw Josey Wales, Unforgiven, A Perfect World, and Birdy – but we also got, well, most of the rest of his oeuvre, to be frank, and the chance of Eastwood reaching deep inside and pulling out something to match his earlier, already rare, best efforts are zero – it’s simply not going to happen.

Now that we’re in a position to judge more or less Clint’s whole filmmaking career, can we look at it unsentimentally and call it what it is: the work not of an artist, or a genius, but of an occasionally brilliant, occasionally lucky, journeyman director whose best days are well and truly behind him.