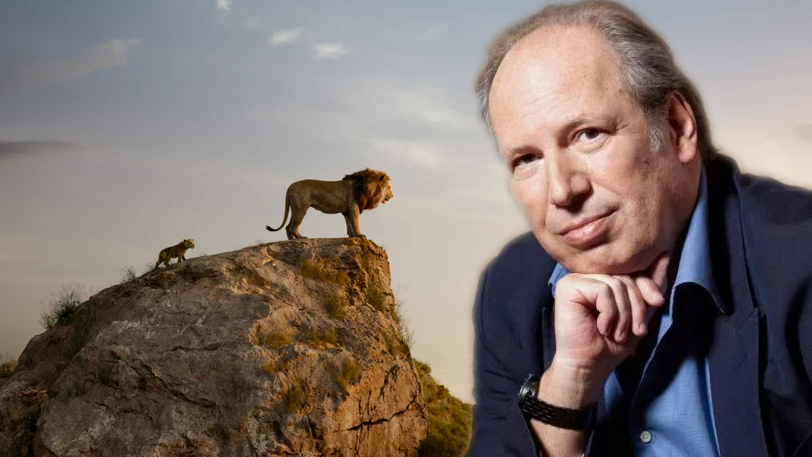

‘I didn’t want to do a cartoon.’ Hans Zimmer on composing The Lion King

Hans Zimmer (who is touring Australia in October) needs no introduction. Sarah Ward sits down with the legendary Hollywood composer to discuss working on the original The Lion King as well as the blockbuster remake, which is currently in cinemas.

Giving one of Disney’s biggest hits a rousing score, The Lion King holds a special place on Hans Zimmer’s resume. It was not only his first animated project; it’s the only movie that’s won him an Oscar.

Over a career spanning everything from Rain Man, The Thin Red Line and Gladiator to Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Interstellar and Dunkirk, the German composer has received ten other nominations. His list of credits only goes on, with Thelma & Louise, True Romance, The Rock, The Ring, Nolan’s Batman trilogy, 12 Years a Slave and Blade Runner 2049 to his name also. Recently, Zimmer began touring live, playing his greatest movie music moments to thrilled audiences – and nothing gets quite the same response as The Lion King.

Returning to the same story 25 years later, the renowned musician again works his magic – but, just as the style of imagery has changed, so has Zimmer’s approach.

With the new version of The Lion King now screening, Sarah Ward spoke with Zimmer about his return to the Pridelands.

A quarter of a century after you won an Oscar for the original film, you were asked to return. What was your reaction?

Jon [Favreau] did it in a really clever way. He just said, “come over, I want to show you something”. That was about it. And he showed me the whole opening and, even though I knew what they could do with computers, I was so incredibly blown away and weirdly, truly emotional. Saying no was just not an option. He had me at hello, as they say.

The story goes that, back in 1994, you were originally reluctant to compose the score. Is that accurate?

Reluctant then, yes, but because I’m an idiot! I said no, I didn’t want to do a cartoon. No, I didn’t want to do a musical. They swore, by the way – they swore up down and sideways – that it’d never become a musical. So much for that!

Then I realised that my daughter, my oldest, she was six years old at the time. Dads like to show off, or maybe it’s just me, but I could never take her to a premiere. I couldn’t take her to a Ridley or Tony Scott shoot-’em-up or something like that. So I was like, “oh god, I could take her to this cartoon. It’ll be fun”.

Little did I know that it’s about the death of a father and leaving the young son behind. And my own dad died when I was roughly my daughter’s age at the time. So suddenly I have to go open up all of these dark corners that I’d conveniently hidden away and deal with stuff I didn’t want to deal with.

How did you tackle returning the same story for a second time?

It’s a bunch of coincidences. Pharrell Williams and Johnny Marr ganged up on me a few years back, and said, “look Hans, you’ve got to get out of your dark, windowless room. Eventually you have you to go out — you can’t hide behind a screen forever, no matter how much stage fright you have. You have to go out there and play some of this stuff live, and look the audience in the eye”.

So then we were going to do the Coachella festival, because I thought, “this’ll be fun, we’ll take an orchestra and a choir into the desert. I don’t think anybody’s done this”. But I said to my musicians, “we’re not doing Lion King – that’s a kid’s movie. Nobody wants to see that.” And Nile Marr, Marr’s 23-year-old son, said to me, “Zimmer, just get over yourself. It’s like the soundtrack of my generation. We’re doing Lion King.”

So we did Lion King. I really do have a crack band – I have the most amazing bunch of musicians who play with such passion and commitment – and I see this sea of people being really affected emotionally by what we’re doing. And I think, now I know how to do the movie.

You have that realisation – what was your approach from there?

I realised that we had to do it as a performance, because we can. It’s not like a normal movie, where you put the music in front of the players and they don’t really know the story, and they don’t know why they’re playing those notes, other than that they’re on the page. Everybody in the orchestra knows The Lion King, so they can play it with commitment and passion.

And I said to Jon, “do you think it’ll be alright if I just rehearse for two days, and then play it?” – as opposed to the way it usually works, where everyone just turns up, you put the music in front of them and start recording, because they can all sight-read. But I really just wanted to get it under their fingers and then perform the whole movie in one go. You know, make it like a concert

With such a vast list of films to your name, what keeps you motivated – especially in The Lion King’s case, when you’re back in familiar territory?

Every artist is never satisfied with what they’ve done. It doesn’t matter how much people liked the score, how many copies were sold, or how well it did at the box office – and that they lied to me and they did turn it into a musical after all.

None of that matters. There are always a couple of ideas left over, and you always want to go and fix a few things. So I thought, “oh this is great. I’m really lucky. I get to go back into my work and fix some stuff.”

Then I realised very quickly as well, don’t overdo it. The important thing is to keep it raw and keep it alive. There’s a way you can polish the life out of things.

In recent years, you’ve contributed to a series of nature documentaries with Sir David Attenborough, including Planet Earth II, Blue Planet II and the upcoming Seven Worlds, One Planet. Given how photorealistic the animal life appears in The Lion King, did it feel like a fitting project to work on at the moment?

Here’s the thing — the world has changed tremendously. Where the first movie was really about my relationship to my child, and my relationship to the death of my father, this movie is extraordinarily beautiful and it shows you nature at its finest.

I’ve spent the last I don’t know how many years working with Sir David, and being aware of how perilous our world has become – and how we really need to go look after nature and be a little bit more aware of that. So, you know even though I’m telling the same story, I have a different emphasis.

Sir David, him just turning up at Glastonbury this year – he’s the most important rockstar there is. He’s the guy who’s been changing the world. He’s the guy who’s been telling us this for his whole life. He’s the guy who, they offered him to be the head of the BBC and he turned it down because he thought it was more important to go and advocate the conservation of nature. He’s an amazing guy. So I’m incredibly lucky to be a part of that conversation, and I needed to be able to put The Lion King into that conversation.