I’m a Bob Dylan fanatic. Here’s what I think of A Complete Unknown

What do Bob Dylan megafans think of his acclaimed new biopic, A Complete Unknown? Flicks’ editor-at-large and resident Dylanophile, Luke Buckmaster, asks “how does it feel?”

I became a Bob Dylan fanatic during my late teenage years, interpreting the famous refrain of Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 as a quasi-religious commandment—an instruction to be followed at all times. More than any recreational substances, songs like Desolation Row, Visions of Johanna and Mr Tambourine Man behaved like consciousness-expansion packs, blowing my mind, activating something deep inside. I read most of Dylan’s songs before I heard them, printing out hundreds of pages of lyrics, which I’m sure had a profound influence on me as I cut my teeth as a writer, entering the jingle-jangle morning of my career.

Others have taken a different, perhaps less fulfilling route into the Dylan legend. To wit: any of those whining sod who’ve attended a concert over the years then complained about how he didn’t address the audience, or didn’t seem to want to be there, or sounded like a frog belching into a cup. Didn’t they pay attention to Maggie’s Farm? Bob does things his own way. There are many strange things in the story of the blockbuster poet: he’s an enigma, a mystery, a song and dance man; his songs mean everything, his songs mean nothing; he’ll let you be in his dreams if he can be in yours.

The main thing James Mangold’s new biopic does right is something it doesn’t do at all. A Complete Unknown doesn’t try to “explain” Bob Dylan. It’s not an attempt to get to the bottom of who he is or what he stands for—and thank god for that. Liberated from the sneering surrealism of Like a Rolling Stone, the title in this context has a different meaning—referring to a person not being understood, or not being known, even after achieving fame and notoriety. The title of the previous Dylan biopic, 2007’s I’m Not There, riffs along similar lines, inferring a state of being present but not present; known but unknown; invisible and in plain sight.

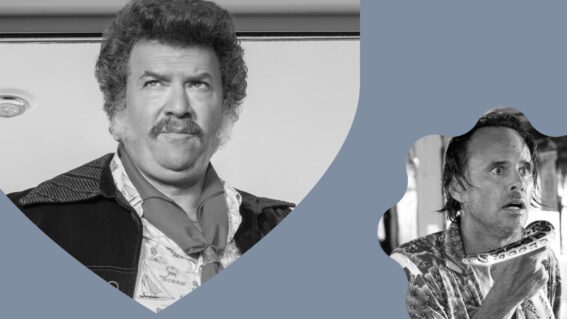

I neither loved nor hated A Complete Unknown. It certainly features an impressive performance from Timothée Chalamet, his tight impersonation leaving just enough wiggle room for the actor to steer it into a space beyond facsimile. Just enough to make it his. The film is a jukeboxy confection with at times a very American, very Hollywood air of unreality, nibbling on concepts of legend and mythmaking but backtracking from anything really interesting or bold. It’s staged literally and non-reflexively, and yet meaning runs away from it, like sand through one’s fingers.

The story follows Dylan as a folk singer breaking into the big time. It begins around 1961 and culminates around 1965, when he transitioned to rock and recorded Highway 61 Revisited (my all-time favourite album). It was inspired by Elijah Wald’s non-fiction book Dylan Goes Electric!, which framed the star’s iconic performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival as a seminal, tectonic plate-rearranging moment in music history. Wald convincingly paints the event as a portal or rabbit hole into another world, without putting his finger on what the other side of that thoroughfare looked like, or what the journey really meant. Like Mangold, he resists a neat—and therefore problematic—thesis. Unlike Mangold, the author acknowledges the slippery nature of truth and perception, at one point prefacing a description of the aforementioned concert with a simple but, I thought, terrifically effective string of words: “we leave the realm of history and enter the realm of myth.”

Another mistake Mangold avoids is the cringey “light bulb moment,” whereby the genesis of a song is illustrated via a neat and reductive moment. For instance: Dylan walks in a park and watches a leaf blowing in the wind, or a man playing a tambourine—a tambourine man!—then returns home to bang on his typewriter and strum his gee-tar. Bish bash bosh—an iconic song is created! Which sounds unthinkably on the nose, but Mangold has done it before. In a scene from his Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line, June Carter (Reese Witherspoon) interrupts a hard-partying Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) and screams at him: “you can’t walk no line!” Mangold then cuts to a recoring studio; no prizes for guessing which song Cash is performing.

As for Dylan’s characterisation, which of course is central to A Complete Unknown, it feels broadly right. “You’re kind of an asshole, Bob,” Monica Barbaro’s Joan Baez says at one point. Maybe, but he’s also kind of not. Dylan’s head’s in the clouds. He’s hungry to make it, hungry to arrive somewhere. He’s not a bad guy but he might not be there for you in your hour of need; he’s got his own fish to fry. In this film the closest we get to expressions of Dylan’s soul, his being, his raison d’etre, are the generously sampled songs, the naked lyrics. Which makes sense. They stand for more than the film ever could.