Inside Silo’s central setting: another great vertical dystopia

The dramatic possibilities of the dark dystopian world in Apple TV+’s Silo kept Luke Buckmaster fascinated, right up to the end. Here’s how it compares to other great sci-fi stories that turn class metaphors into literal structures.

“Dystopian” isn’t a word one drops into an ailing conversation in the hope of bringing it back to life. It’s a cold and mean word, connoting terrible things: oppressed societies; authoritarian governments; grubby marketplaces where people dressed in potato sacks barter for non-contaminated water. It’s also a term that, for visual storytellers, is full of imaginative opportunities, filmmakers since the early days of motion pictures clambering to create spectacular dystopian settings.

With the arrival of the terrific new sci-fi series Silo, created by Graham Yost, we’re getting one for the ages: an awesome central location brimming with dramatic and aesthetic possibility. You won’t want to move into this glorified bunker any time soon, but by god you’ll want keep returning televisually. I smashed through the entire first season in a few days.

The titular place, originally created in Hugh Howey’s post-apocalyptic novels, is a huge underground edifice, hundreds of stories deep, where 10,000 people live. Nobody knows who built it, why they’re there or what happened to the world outside, which is believed to be toxic and uninhabitable. Anybody can leave at any time…but they can never come back. Director Morten Tyldum frontloads striking images of the setting that scream “this show cost a megaton.” We see for instance one floor containing cows grazing on grass—another growing crops and a cafeteria with a wall-covering window displaying the grayed and decayed external environment.

As the series progresses we experience more of the space, most prominently a massive spiral staircase in the middle of it, which functions like a verticalized town square. Plenty of reviews will give you the lowdown on the story, characters, performances etcetera. Here I’ll stick closely to the space itself, unpacking what makes it a striking location and how it reflects and extends a long lineage of sci-fi concepts. I haven’t read the books, so these observations are based entirely on the series and comparable productions.

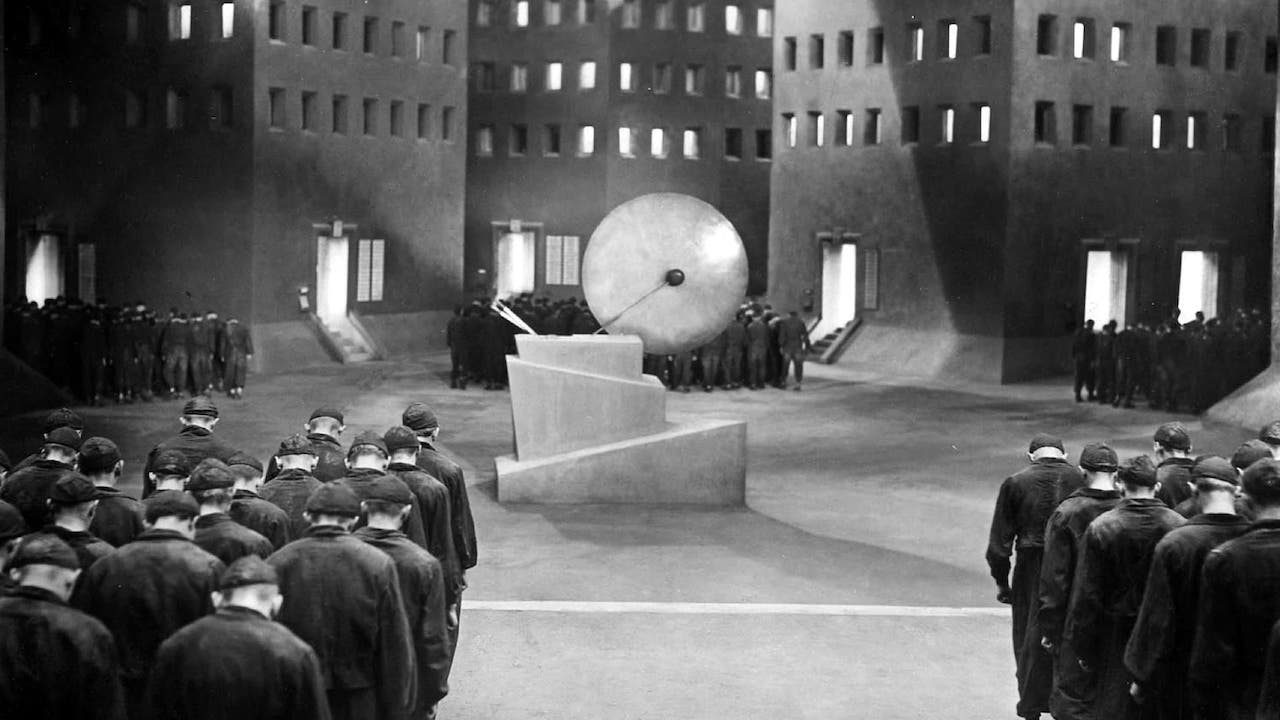

Firstly, Silo continues a long history of using verticality to represent class structures and social factions. Privileged people live towards the top and poorer people, called “the down deepers,” exist below. Hard-knuckle protagonist Juliette (Rebecca Ferguson) is one of these. Picked by the sheriff (David Oyelowo) to be his predecessor, for reasons unpacked early in the series, Juliette ruffles feathers by rocketing up the food chain and bypassing the established hierarchy. This is the reverse of the trajectory undertaken by Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) in Fritz Lang’s seminal Metropolis, who leaves idyllic gardens in the sky, where the affluent live, to explore the industrial bowels of the titular city—where he witnesses workers suffering horrific conditions.

Organising dystopian societies by literally placing the upper class above the lower is an oldie but a goodie in science fiction. The title of Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium is the name of a huge space station orbiting above earth, which has luxurious houses, effervescent landscapes and medical treatments to cure all sicknesses. This is where the affluent live. Down below is a planet in smoking ruins, where common folk—including Matt Damon’s protagonist Max—toil and languish.

In Ben Wheatley’s adaptation of J. G. Ballard’s novel High-Rise, which is based in an apartment building, the well-to-do similarly hog the top levels and the poor dwell below. In Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s The Platform, which uses a vertical prison and its rather…unconventional catering service to allegorize wealth distribution, the people high up stuff their faces and those underneath suck on scraps. In Snowpiercer, which is set on a train, the concept is flipped from vertical to horizontal: aristocrats near the front, paupers towards the back. Like Freder, Max, and The Platform’s troublemaking lead—Ivan Massagué’s Goreng—Juliette is an agent of change, ushering in a period of intense destabilization.

The silo in Yost’s series is also used to flesh out various customs, lores and traditions the community has developed over time. Like in many dystopian stories, from The Handmaid’s Tale to The Hunger Games, these provide narrative details while allegorically commenting on aspects of our own reality. The commentary is broad in Silo, making a point about human tendencies towards order, structure, authority and the strange shit people do to commemorate the past.

Early on we watch citizens celebrate “Freedom Day,” during a darkly beautiful public ceremony involving orange lamps that float upwards, alongside that magnificent spiral staircase. The complex’s long-dead architects have been elevated to the level of gods, revealed through lines like “I’ll pray to the founders you’re right.” Depicting aspects of religiosity is a nifty way to express a society’s values—often, in dystopian fiction, referencing things that have gone terribly wrong, or some kind of underlying perversion. The War Boys in Mad Max: Fury Road for example worship at an altar made of steering wheels, and use chrome spray to symbolize purification (“witness me!!”).

I love, also, how a thick sense of mystery permeates the air in the silo. There are many questions, including who’s really running the show, why dissenters regularly turn up dead, and what became of the outside world. It’s clear from the first episode that the top brass are hiding things from citizens, channeling another evergreen theme: government conspiracies and political gaslighting. In Soylent Green, Charlton Heston’s chest-beating truth-seeker famously goes on a mission to discover what a nutritious government-provided food is really made of, and arrives at a shocking revelation (“Soylent Green is people!”).

What Juliette will discover in Silo is the $64,000 question. No spoilers here—but I can assure you, you’re in for quite a ride. The surprises keep rolling until the very last shot of the final episode, which contains a big reveal, and is a great example of visual storytelling. Like the show’s setting, it too is one for the ages.