Interview: Mark Levinson, director of ‘Particle Fever’

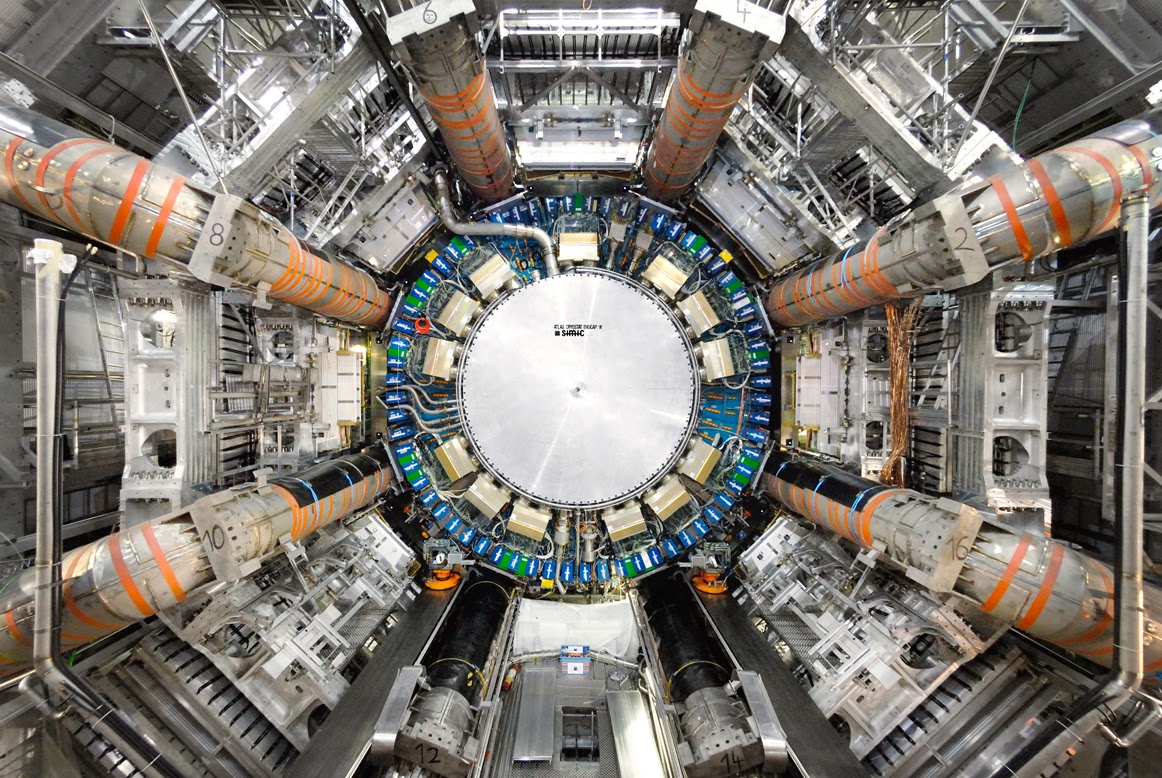

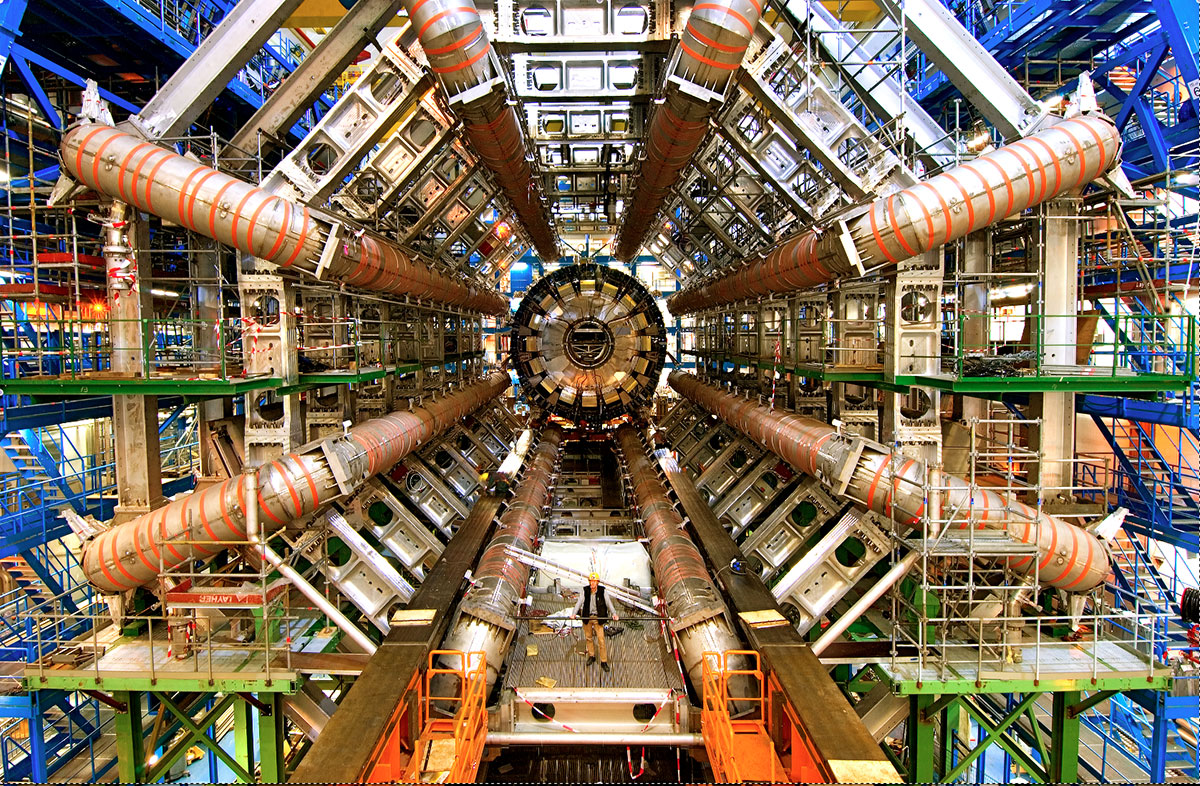

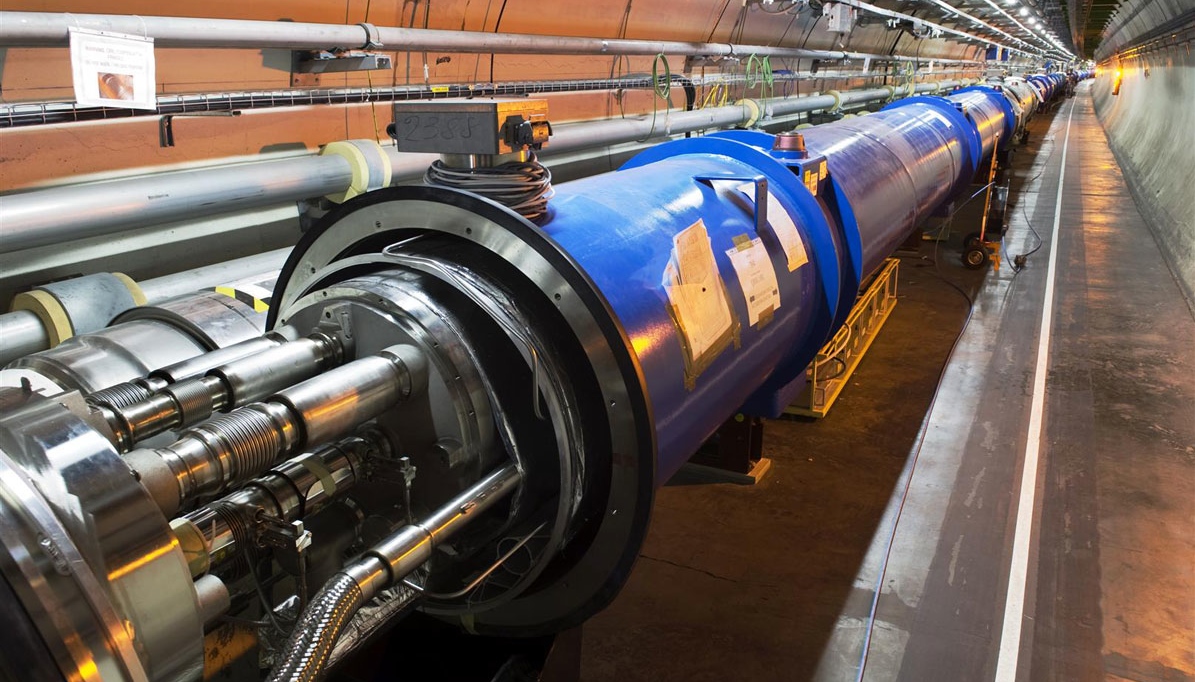

Twenty years in the making, the 18-mile-long super-collider at CERN in Switzerland was developed to uncover the mysteries of the universe – by smashing things into each other at enormous velocity. NZ International Film Festival documentary Particle Fever captures the moment the collider was first switched on, the people who have dedicated much of their professional life to making it happen, and the huge scientific breakthrough made. Director Mark Levinson took the time to answer our questions about the film – including the doomsday scenarios floating around just prior to the super-collider’s start up.

Hello from Flicks. What have you been up to today?

Enjoying a very warm NYC summer day – and had to watch a bit of the World Cup final since my wife is German!

When did you make your first visit to CERN, and what emotions did it conjure up?

I first went to CERN in August 2008. It was really the first shoot for Particle Fever, and I went ahead of my crew to try to get a bit of a sense of the lay of the land. I certainly felt excitement – both my own at finally being there, and the excitement of the physicists who had been waiting for the LHC to start up for so many years. But I also had a very strong personal emotional reaction stemming from the fact that I had studied particle physics myself and had a PhD in theory. At lunch, many of the theorists eat together in the main cafeteria, and I remember sitting with them and thinking, if I had continued in physics, this is exactly where I still might have been that day, but “on the other side” of the table. It was an odd feeling of déjà vu, although in fact, it never really happened. But it could have and I felt a very powerful connection to my past life.

Was this in the construction phase, or closer to when it was due to be fired up?

It was just a couple of weeks before they were going to do the first tests to send beams entirely around the 17 mile ring. The date had been widely publicized for “First Beam Day,” and many press people were coming, so there was a lot of pressure to be ready. And of course, all sorts of last minute things were coming up. And there was still “construction” going on. People were working incredibly long hours. In retrospect, I’m amazed at how generous people were with their time with me.

Was the conjecture as to what would happen when it was switched on, in particular the more catastrophic prophesies, something also being discussed among the scientific community?

The main thing everyone was focused on was making sure they were ready – and hoping it would actually work! Could they get this beam of protons moving at nearly the speed of light to stay in its path all around the 17 mile ring? In terms of catastrophic prophesies of creating a black hole that could destroy the universe – it was “discussed” only in the sense that it was ridiculed. First of all, they were initially only sending a single beam in each direction separately. There weren’t even any collisions scheduled to take place at all at this time. Secondly, even when they did get to the point of having high energy collisions, the same theories that predicted that mini-black holes could possibly be created, also predicted that they’d evaporate almost instantly. The people predicting apocalypse (principally a high school science teacher from Hawaii), clearly didn’t read or understand the entire papers.

What did you think about such concerns?

I thought like the physicists. Of course, when I saw a headline in the Geneva newspaper with a glaring headline asking “Will the universe be destroyed tomorrow,” I immediately filmed it!

Did the doomsday prophesies, and just the process of getting the collider operational, overshadow the actual science being done?

I think for sure the initial stages were dominated by operational concerns. Until they had high energy collisions, nobody expected to see new physics. There was a collider outside of Chicago, the Tevatron, that was chugging away, and still getting good data. The LHC was only initially scheduled to start with low energy collisions, lower than the Tevatron was already running. So, initally, they only expected to confirm things that had already been seen. In fact, that would be a great test that the machine was working and they were understanding their detectors and data. But of course, everyone was looking toward the time when they had higher energy collisions than the Tevatron. And the grand hope was that they’d then see something new. In fact, at the time, everyone expected they could see new particles not in the Standard Model before they’d find the Higgs.

What was it like observing and documenting such a colossal technological and scientific achievement?

I don’t think it really hit me how historic this period of time would be until near the end. Most of the time when I was filming I was very pre-occupied with the practicalities of filmmaking – am I in the right place, are we getting sound, do we have enough tape, are our batteries all charged? And very conscious of the fact that I was filming non-reproducible events and needed to get it right. Certainly that was true for the big July 4, 2012 Higgs announcement. It was only at the end of that (very long) day when I went back to my hotel room and went on the internet and saw that every website, every newspaper, every blog was talking about the Higgs boson that I felt a tremendous thrill and satisfaction that I had witnessed a truly historical moment in person. On that day, at least, I felt I was truly at the center of the universe.

If you were to repeat the experience with a new scientific institution, what would it be? Even if it hasn’t been built yet.

I really was spoiled a bit with Particle Fever. It was such a unique situation in science, with an entire field focused on one experiment that people had been waiting for for so long. Thousands of people waiting for something that could have deep implications for our fundamental understanding of the universe. And there was going to be a definite “turn on” moment. I don’t know of anything else like it at the moment in any other field. There’s of course lots of huge things that could be discovered in many other experiments, but nothing with such clear dramatic potential from a filmmaking perspective. Actually, what I think about more isn’t in the future but the past – I wish I was filming when they performed the first test of an atomic bomb at Los Alamos, or during the period around the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA. Those could have been great films.

What was the most memorable moment of the shoot?

I think it’d have to be the July 4, 2012 announcement of the Higgs discovery. Not only was it so historic, with Peter Higgs present himself, confirming something that I had even studied myself at a certain point – but it was also clearly the end of filming for Particle Fever. We knew this was the definitive end for the film.

Who would be the best, and worst, people to bring along to your film?

The worst would be people who just have no intellectual curiosity. The best – everyone else!

What was the last great film you saw?

When you’re on the festival circuit, it’s actually very hard to see other films. I’ve found that it takes a couple of festivals to catch up with films that have been with you on a number of occasions, but the timing never worked out to watch them. One of those films was a Polish film called Ida. I actually didn’t even think it sounded that interesting when I first heard about it at Telluride. But people kept talking about it, and it played with us at several other festivals and people would continually ask if I’d seen it. And when I finally saw it, I was really blown away. Simple, and yet also complex and layered. Very powerful.

What are you thinking about doing next?

I’m really interested in exploring the art/ science overlap more, and there’s a novel that I read before I did Particle Fever that I think brilliantly looks at molecular biology and music, in the context of a very human story. It’s called The Gold Bug Variations, by Richard Powers. I’m starting to write the screenplay now.