Is The Burning Girls schlocky folk horror or prestige crime drama? Why not both?

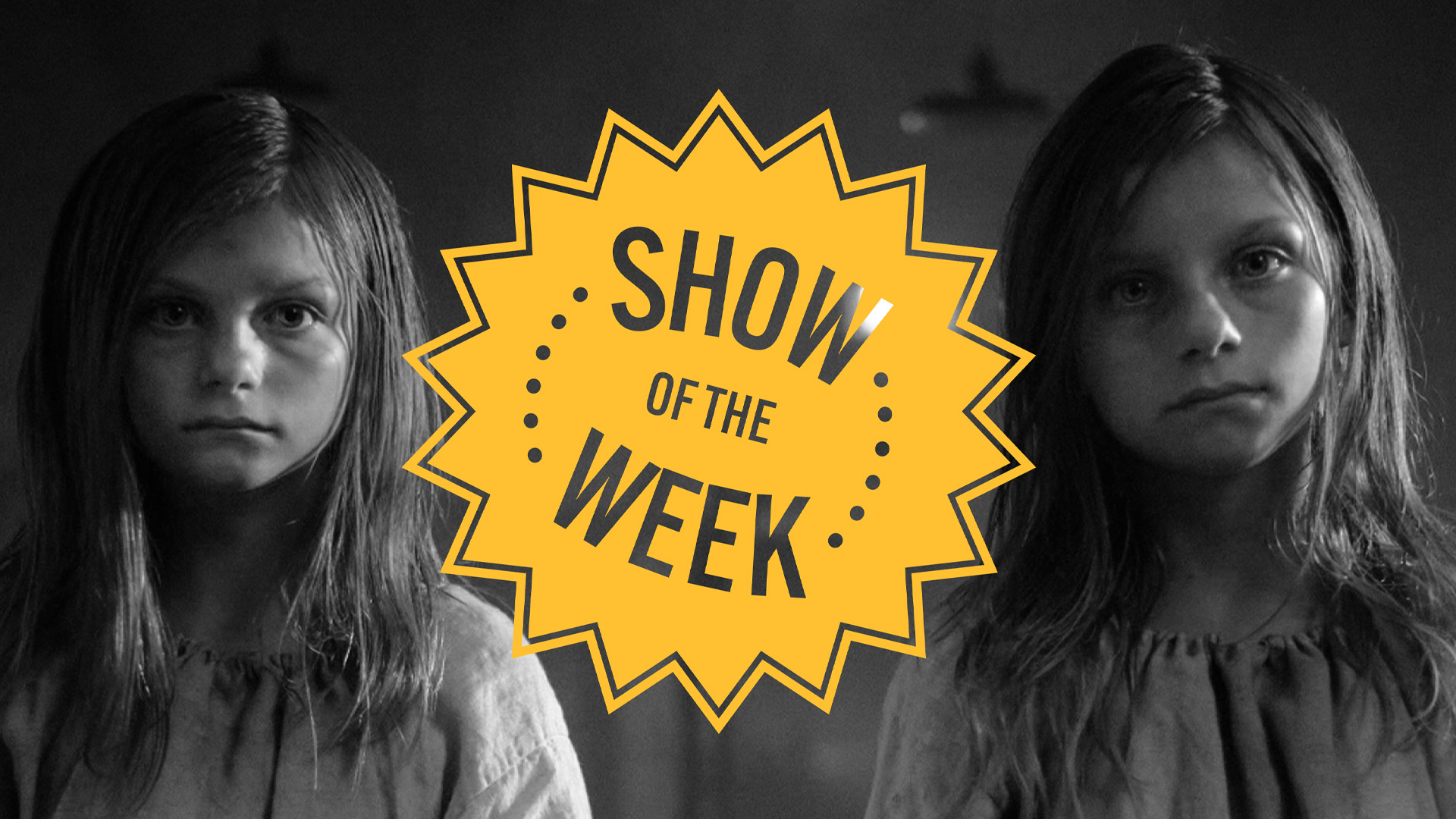

We’re all drowning in content—so it’s time to highlight the best. In her column, published every Friday, critic Clarisse Loughrey recommends a new show to watch. This week: A new vicar arrives at a creepy village church in The Burning Girls.

Paramount+’s new series, The Burning Girls, counts as folk horror—but only if your central reference point for the genre is not 1973’s The Wicker Man, but the 2006 remake starring Nicolas Cage. But, really, that’s part of the slightly schlocky, junk food appeal of the show, which adapts CJ Tudor’s bestseller about a village with more bloody secrets than any of the places in Midsomer Murders—and then pumps it full of so many jump scares that its main character, Jack (Samantha Morton) has to beg the sinister church warden with the Crispin Glover haircut to stop creeping up behind her.

Jack is the new vicar, arriving into Sussex’s Chapel Croft village, whose chief claim to fame is the burning of two young girls at the stake in 1556, as part of Mary I’s purge of the Protestants. The place is now randomly littered with small, straw effigies of the martyred pair, thrown into a large bonfire by residents at some yearly festival that is definitely—not at all—cult-like. A local saying warns: “If you see the burning girls, something bad will happen”. So you can bet your Paramount+ subscription that Jack can barely get through her first night without the stubborn, screaming little ghouls turning up on her doorstep.

The rest, really, writes itself: it’s nearly impossible for Jack to walk from one end of the churchyard to the other without some disembodied voice chattering away in her ear. Her sullen and rebellious daughter bonds with the local sullen and rebellious boy (Conrad Khan), all because she loves taking pictures of graves with her dead dad’s camera, while he loves drawing pictures of demonic goats climbing out of graves. Together, they go check out the local satanic graffiti scene.

Yet, what’s striking about The Burning Girls is that it also, partially, qualifies as a prestige crime drama. Jack has her own dark history: a fatal incident that took place at her previous parish in Nottingham that may or may not have involved an exorcism, and may or may not be the reason a mysterious box with a bible, a bloodied knife, and a vial of holy water has turned up at their new home. Either way, she’s tormented by nightly flashbacks. Morton, who’s an immensely talented actor, constantly reroots the show in the tangible and relatable, even when the whole thing’s one jump scare away from flying completely off the rails. She plays Jack as if she were the brilliant, but conflicted, detective of a Scandi Noir.

Are these phantom tykes actually stalking the church grounds and ruining people’s sleep? And are they somehow related to the sudden disappearance of two teenage, borderline delinquent, girls over thirty years ago? And the untimely death of Jack’s predecessor? And the other untimely disappearance of Jack’s predecessor’s predecessor? And the fatal accident that befell a local reporter’s child? If they are, they’ve really been clocking in the hours.

The Burning Girls sees the very silly and the very sober chase each other around circles like two feral cats—and, with only three episodes made available to critics, it’s very hard to tell which one will eventually win out. For anyone unfamiliar with Tudor’s source novel, that’s sort of the appeal here. Its true mystery isn’t who did what or who killed whom, but whether these ghosts are real or part of a very elaborate, human-led cover-up, just like every episode of Scooby-Doo (minus that one film about the island filled with werecats that scarred me as a child).

Alternatively—and this is categorically the least interesting possibility—all these manifestations will be hand waved away as some generalised symptom of “trauma”. That’s certainly how the Scandi Noirs would handle it. And that’s also maybe why television could do with a little more of The Burning Girls’s goofiness.