John Carter Of Meh?

[Ed’s note: Click here for Flicks’ review on John Carter]

I don’t really like the idea of doing ‘film reviews’ of in-release films in a blog like this, but this week I have to make an exception with a little film currently doing the rounds called John Carter.

Perhaps you have heard of it?

For good and bad, John Carter is all that Los Angeles and the film world is talking about this week – not because of the merits of the film per say, but rather the fact that it’s currently touted as an unmitigated disaster for the Walt Disney Company who blew an epic $350 million USD on what has become, ostensibly, as a tepid family film that is set to shake nobody’s tree. The close post-mortem on the film for many in the industry reveals a fascinating insight into the processes of blockbuster generation and the film business, especially when gambling with a project so vast and outrageously expensive that it threatens the financial stability of a major corporation.

If nothing at all, I thought this could be an chance to do a comprehensive assessment of a film both from the perspective of historical context, number-crunching analysis (provided by other publications) and an aesthetic review to use for comparison. Here-in, we join the party and take a look at what may have went wrong with Disney’s John Carter.

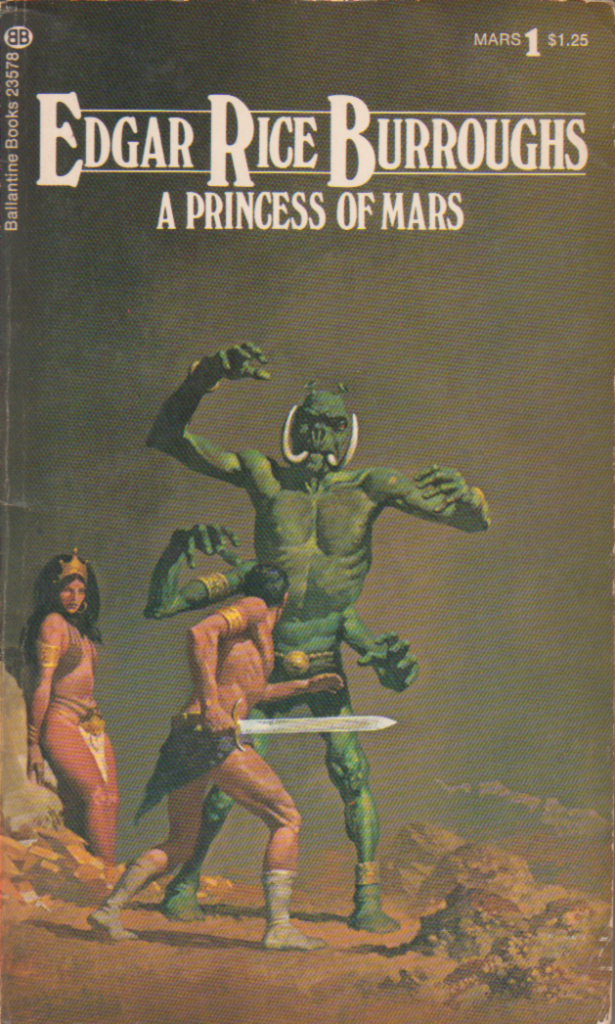

Disney’s John Carter is a cinematic adaptation of the first volume of serialized stories by writer Edgar Rice Burroughs (creator of Tarzan). First published in 1917 in full novel form, the book ‘A Princess Of Mars’ was a classic example of early 20th Century pulp fiction, weaving a fantasy epic whereby a Civil War soldier Captain John Carter is transported to the planet Mars (called Barsoom in the novels) by way of astral projection. Mars, which contains a breathable atmosphere at the time plus two species of martial inhabitants, one quad-limbed and green (called Tharks) and the other humanoid and with a penchant to wear as little clothing as possible.

Carter’s numerous adventures on the planet Mars where by he conquered empires, brought peace to the planet and scored with the Martian’s hottest and constantly near-nude damsel-in-distress Princess Dejah Thoris became the basis of a series of books eponymously referred to as the ‘John Carter Of Mars’ series. Constructed as a mixture of science-fiction, sword-and-sorcery and epic western, Burroughs books went on to directly inspire (through imitation and homage) many of the stalwarts of modern sci-fi/fantasy fiction in literature, comics and film such as Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Martian Chronicles’, George Lucas’ Star Wars saga, the character of Flash Gordon and – most recently and obviously – James Cameron’s AVATAR which the film of John Carter is being given a direct and uncomplimentary comparison to by critics. To be fair to the makers and Disney, this franchise is something of a holy grail for fans of the genre, like going back and adapting Tolkien if he was a pulp writer as opposed to the father of high fantasy. A ‘John Carter Of Mars’ movie has been in the works for almost 80 years in some part of Hollywood or other, ranging from plans for an animated production back in the 1930’s to a sci-fi epic in the 1960’s, an action franchise in the 1980’s and finally realized in 2012. In short, whenever science fiction reared its head in popular culture, there was a John Carter movie waiting in the wing, though none of them ever got made until now.

The company that finally got to make it turned out to be the Disney, which many fans of the novels felt was a a strange choice considering the pulpy elements of the story with its blood, violence and highly sexualized content that is more fitting for the world of ‘Conan The Barbarian’ rather than Mickey Mouse and The Lion King. Never-the-less, since Disney had successfully turned vicious, cutthroat, 17th Century pirates into family-friendly fodder it seemed possible that ‘John Carter Of Mars’ could get away with the same treatment. Disney, itself undergoing something of a massive boom in its live-action film department (the first since the early 1980’s) with franchises like Pirates Of The Caribbean, Tron Legacy, Alice In Wonderland, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and Prince Of Persia, had established a very notable ‘Disney style’ of PG-rated, family-friendly, epic blockbusters that used production value to attract the grown-ups and simple, often watered-down and then ‘cranked upto eleven’ stories that the nine and ten-year-olds in the audience could follow and not be too confused by. The project, championed by director Andrew Stanton who was the brainchild of many award-winning films at Pixar including A Bug’s Life, Finding Nemo and WALL-E, seemed like it could fit if Disney didn’t let its focus-group and corporate mentality derail the creative vision.

The production of the film had its share of problems, if you’ll believe the write-ups such as this one from the New York Times. Stanton, though by all rights a creative sacred cow in the annals of Pixar, was venturing into the world of live-action filmmaking for the first time and live-action filmmaking is nothing, absolutely nothing, like animation. Stanton himself admits that he expected the extensive reshoots that had to be executed at the end of production because as someone learning how to creatively work in the frame-work of live-action, he was bound to make mistakes. The film starred a relative ‘unknown’ (possibly attempting to emulate AVATAR‘s casting strategy) and, unlike most of Disney’s prior live-action mega-films, this was based on a work that Hollywood tracking numbers would deem as ‘obscure’ by audience standards compared to films based on a theme park ride or a successful video game or a popular children’s story. Perhaps again Disney was banking on riding the success of Cameron’s AVATAR, a film after all that had no stars, a plethora of goofy alien creatures and an original story inspired BY ‘John Carter From Mars’, since studios like to believe that once a ‘pathway’ has been cleared in an audience’s mind then it becomes easier to revisit those familiar paths (in theory). Accustomed to reworking scenes over and over until perfection (common in animation), Stanton commissioned not one, but two reshoots and engaged with his creative Pixar staff to brainstorm new scenes, ideas and story gags after principal photography had wrapped. And as the film neared completion, the movie’s now infamous and derided marketing campaign kicked into high gear:

When the world got its first look at the ‘John Carter Of Mars’ movie, now retitled with the very vague, bland and ‘so what?’ moniker of simply John Carter, the denizens of the Internet and movie-buffs who were in the prime target zone for the film felt very mixed indeed. While there were strong elements that hooked a small level of hype from hopeful fans, industry experts, critics and film-tracking websites took note of some genuine red flag material: the film’s bland print campaign (apparently controlled by Stanton), the cartoon-ish digital creatures, the lack of acknowledgement on the film’s source materials or its legacy (one would have thought they’d name-drop the shit out of Flash Gordon, Star Wars, AVATAR and every other classic film that owed something to John Carter), its over-reliance on spectacle that – even in the trailer – looked phoned-in, cliche and lacking a singular directorial vision. Many cited the shortening of the film’s title to the confusing and non-descriptive John Carter as a sign of the overall treatment of the film and the source material…and then the Internet hate-machine really cranked to life. The Los Angeles Times reported on the poor tracking numbers on the film; surveying film-goers only to find that audience members either didn’t care for the film, didn’t know anything about it and/or couldn’t decide if it was something that they actually wanted to see – signs that a film’s marketing has failed in its purpose (and to that effect the film’s actual short-comings could be derailing the marketing to boot). As the months went by, building up to the premiere, the number-crunching factories in Hollywood began to show signs that this film could be in desperate trouble if the movie didn’t turn out to be an instant classic that hit its viewers with an experience that could result in word-of-mouth success.

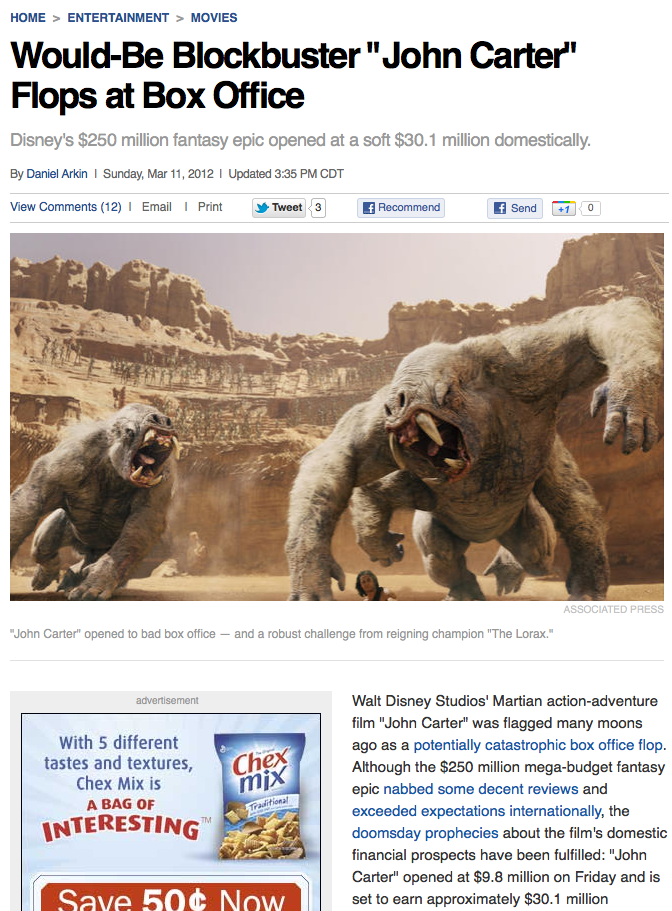

And thus, the film opened this weekend:

How is the film? Well opinions are certainly divided.

In the number-crunching game of Hollywood, there is a theory that critical opinion can be a good indicator of execution while box-office is the all-powerful indicator of success. Amidst these two sections, the ‘audience opinion’ is irrelevant because how many people claim to like or dislike a film rarely corroborates with box-office turnover, especially for a ‘mixed review’ film like this one. Aggregate film review site Rotten Tomatoes scores the film with a total rating of 49%, suggesting that half of the reviewers gave it a ‘favourable’ rating while the other half did not. Out of almost 18,000 registered users on the same sate, 72% of them gave it a ‘favourable’ rating which could initially suggest that audiences are connecting with the film even if critics are not. Of course this is not the case as established before – vocalized audience opinion (especially on the Internet) and box office does not often correlate. Box Office Mojo, one of the industry’s premiere analysis services, shows the film to have taken $30 million USD within the United States and $70 million USD everywhere else, bringing the weekend total up to a grand $100 million USD. Sounds like a lot of money? For you and me, it definitely is, but for a $350 million movie with a marketing budget probably within $100 million in of itself, it’s bad news.

Very bad news.

Because of Hollywood’s hit-and-run, ATM-bank-robbery tactics with movie releasing, there is an established precedent to attempt to recover the largest amount of money in the film’s opening weekend with the knowledge that a film will make less money as the days go by from that weekend onwards. It is generally ideal to make at least 60% of your film’s budget back in the first three days or else you could be looking at a long and drawn out process of trying to recoup costs via TV, VOD and home video sales which, ultimately, may mean that your film might break even, but never actually turn a net profit. For John Carter, the weekend numbers seem to spell its doom for the movie, the future of the franchise and Disney’s ability to cope in its next financial term. The bad news gets worse as the media, who will always swarm around a fresh kill by the scent of its blood, has picked up the story of the film’s floppy-ness and run with it. The word is out and John Carter is, for the moment, arcing along the trajectory that analysts predicted and the studio had feared. This news (and the media frenzy) is further compounded by the sudden departure of Disney’s controversial head marketing manager M.T. Carney who may (or may not) share some of the blame on the failure on the film’s bland advertising which so curiously ignored and bypassed all the strengths the source-material had in order to hook into a particular kind of audience.

And how does the actual film hold up? Well, as far as this reviewer is concerned, you’d best forget the glowing audience reviews circulating the web as a sign of majority-opinion on the matter. It is a given that just because there’s a lot of something or that something is very loud on the Internet doesn’t mean that it is an accurate depiction of the true statistical demographics, especially given the discrepancy in box-office tallies. There are a lot of people saying that John Carter is a perfectly fine and great film.

I am not one of them.

Whenever Disney goes through its bad phases, of which there have been many notable eras over the past 80 years, they seem to default to a time-honored and completely incorrect notion that children don’t know what bad acting looks like, what bad writing sounds like and that they need everything constantly ‘cranked up to eleven’ in case they might slip into a coma in the cinema. John Carter is, going by this philosophy, clearly made for an audience under the age of 10.

Pretty as it is and dotted with some genuinely spectacular visual effects, it seems ironic that a pulp story that inspired so many great books and films in the last century has become a film that comes off looking infinitely more infantile, nonsensical and boring in just about every way. As BBC film reviewers Mark Kermode and Simon Mayo point out, the film pleads, nay it begs, for legitimacy by simply inundating you with one pointless spectacle after another that doesn’t contribute to the story, move the plot forward or develop the characters rather than simply scream “LOOK HOW MUCH ALL THIS COST! WE’RE GOING ALL THE WAY HERE JUST TO SHOW YOU HOW CLEVER WE ARE AT MAKING PRETTY THINGS THAT COST LOTS OF MONEY! We could’ve avoided all this and made a shorter film where every scene pushes the story along, but WE DECIDED THAT TAKING LONG TANGENTIAL SIDE-TRIPS TO POINTLESS PLACES AND MEETING EXPENSIVE CGI CHARACTERS IS A MUCH BETTER USE OF OUR TIME”.

The film is also stunted by some truly terrible performances that only an animation director could love. For my part I think its mostly the result of actors being utterly lost with the wordy, exposition-heavy, character-development-lite script where they’re forced to rely on their own tricks to make it to the end of each scene since Stanton can’t help them get across the finish line. A classic example is the movie’s uber-villain Mark Strong; a guy who’s always good in everything he does, but has a very distinctive ‘auto-pilot’ performance when he’s not being pushed by a good director and Strong is definitely on auto-pilot in this film as you’ll find it impossible to tell him apart from the bad guys he’s played in films like Sherlock Holmes or Kick-Ass. Leading man Taylor Kitsch, also clearly out on his own, decides to imbue John Carter with a hilarious movie-trailer-voice-over style of speaking and also figures that since writer/director Stanton hasn’t bothered to do any research on the American Civil War and the people of its time, there’s little precedent for Kitsch to bother either. Lynn Collins, portraying the eponymous Dejah Thoris, Princess of Mars, certainly has the physique to portray the shapely character realized by many artists over the years and would do them all (particularly Boris Vallejo) proud, but despite Stanton’s misguided need to bolster her character by turning her into an ass-kicking, sword-swinging, princess warrior who-also-happens-to-be-a-brilliant-scientist, she also fails to negotiate past the bad and heavily jargonated dialogue her character is forced to spout.

Worse than all of these aspects however is the generic, bland, meandering and seemingly never-ending narrative that ignores the rules of good, lean, efficient, emotionally-powerful storytelling in order to visit set-piece after mind-numbing set-piece which goes nowhere. Stanton’s script, which suffers from classic writing problems that dog Hollywood productions, is over-stuffed to the brim with so much useless detritus that it feels like there’s ten different, vaguely inter-connected, movies rolling around inside of one. We get treated to a plague of archetypal setups and subplots including: epic war scenes, sword-and-sandal tropes, sword-and-sorcery tropes, forbidden marriages, spoiled-princess-who-just-needs-a-man, religious pilgrimages, messiah story, buddy-movie tropes, boy-and-his-dog story, stranger in a strange land story, God-is-actually-technology story, environmental messages, Machiavellian politics, Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey”-lite, Pixar’s patented win-your-place-back-in-your-home-community story, woman-trapped-in-a-man’s-world story and good, hard serving of zero chemistry between the leads. Stanton pulls out all the stops, raiding from plot devices last seen in Saturday Morning Cartoons like a shape-shifting baddie who constantly shifts his shape several times in a scene just to really drive the point home in case you missed it the first time or Dejah Thoris’ introduction where she’s doing that timeless Disney princess classic cliche of rehearsing-an-important-speech-in-her-chambers so that we can tell she’s not only important, but also vulnerable and funny or just the simple mistake of ignoring the logic of the world you’ve set up just so you can do something stupid and spectacular, like John Carter’s ability to kill anyone with a single punch which means that he then spends the entire movie fighting with a sword instead. Wrap all this up with a failure to evoke the pulpy atmosphere of Burrough’s original text (which is far better realized in AVATAR and even The Phantom Menace of all things!) and you end up with a movie that embodies the worst kind of collateral damage Disney and Hollywood are capable while having all the best of intentions.

But of course it’s not all terrible. As I’ve said before, the visual effects are pretty darn stunning (for everything bar the creatures which look like extras pulled out of Pixar’s animation department) and probably some of the most realistic and engaging environments and technical devices seen in a long time. The visuals of Mars are a highlight that make the film tolerable to watch, especially the design of the martial cultures in terms of architecture and costumes which are memorable and inviting to say the least. Barsoom is certainly a beautiful place in this film and the film never lets up in reminding you, time and again, of the vastness of the landscape (and by proxy the epic scale of the canvas upon which this story is being played out). For my part I feel that the most talented people on this entire project were the design team who successfully created a palpable and enviable culture for the two species of inhabitants on the Red Planet that would engage younger and older audiences. And many of the action sequences are not only ripped straight from the words of Burroughs, but realized with admirable skill (usually because Stanton’s directing would take a back-seat to the influence of the pre-visual artists who are better at composing shots and telling visual stories than he is).

Pulling back out even further, there’s the film’s turgid and overblown music score by over-rated composer Michael Giacchino which is constantly present, loud, telegraphing everything happening on-screen and unmemorable enough to get on your nerves after the first 20 minutes. And even beyond all the technical aspects, the film still wrestles with its quaint early 20th Century pulp fiction roots where women were objects to be possessed and just needed a man to tame them, where white men conquered inferior races and the blood of battle washed away all your sins; aspects that were subverted or cleverly avoided with John Carter‘s closest comparison AVATAR, but in this film it is merely disguised with a lot of hand-waving and a political-correctness that feels disingenuous (probably because it’s done in the style of Disney) and would have probably worked better if it was embraced whole-heartedly…not that it would’ve helped get more seats into the theaters these past four days.

I’ve always said that the best kinds of films are ones that are either excellent (duh) or terrible (huh?). Whether a film is brilliantly executed or done so shoddily that you can’t help, but laugh…either way you’re watching something interesting. As a completely mediocre work that barely registers on the brain-activity scale, Disney’s John Carter is – in some ways – the worst kind of movie: so middle-of-the-road, so underwhelming, so paint-by-numbers that you can’t even stay awake, a text that gives out almost zero stimulus. And that’s how it was for me when I saw this movie.

You may be getting the impression that I have built up some genuine hatred for this movie and the truth is that I don’t hate it. I’m just severely disappointed that so much money went into producing so little entertainment…and judging by the performance of the film to date, it seems audiences and Disney themselves are disappointed too. And of course there ARE countless positive reviews of this film which counter my obnoxious opinion and that’s fine; it’s good that the movie has AN audience even if it seems to be a slightly-too-small one. But at the end of the day, the perceived failure of this film – with all its overblown VFX and action sequences and cast of hundreds – by Hollywood will have an ongoing impact into the business decisions made about what kind of films are going to be produced and who they are going to be produced for.

As an industry-worker and someone who is attempting to become a full-time filmmaker himself, these are just SOME of the ways in which we have to critique films and assess the impact they have in an ever-shifting industry where the difference between an Oscar and a historic bomb is the margin before and after someone thought it was a good idea to give this franchise to Disney and the hands of Andrew Stanton. I hope you’ve enjoyed going through this process with me and that it will make you think more about the perceived notions of ‘success’ and ‘failure’ in regard to films.

Thanks for reading and be sure to let me know how you found John Carter, if you have seen it or plan to see it.