Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull remains a problematic, often beautiful film about ugliness

40 years ago, Martin Scorsese released one of the most significant boxing films in cinemas with Raging Bull. But why would anyone even want to make a film about “cockroach” Jake LaMotta? Matt Glasby enters the ring with Scorsese’s problematic, often beautiful film.

In November 1980, Martin Scorsese released one of the most divisive movies of his career. The story of Bronx world middleweight boxing champion Jake LaMotta (1922-2017), Raging Bull remains a problematic text some 40 years on, an often beautiful film about ugliness.

Star Robert De Niro first brought the project to Scorsese, having read LaMotta’s autobiography on the set of The Godfather: Part II. Initially, the director rejected it because he found the sport boring, but after the failure of his musical New York, New York (1977), and a near-fatal drug overdose, he reconsidered. Boxing, he saw, was “an allegory for whatever you do in life… you make movies, you’re in the ring each time”.

Together, the director and star retooled a script written by Mardik Martin (Mean Streets) and polished by Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver). It’s not hard to see why it appealed—to them at least.

For Scorsese, it was a New York story exploring masculinity, the mafia, the (im)possibility of redemption and the dark poetry of violence. For De Niro, who would win his second Oscar for the role, it was a chance for total immersion. Much has been made of the actor’s intensive boxing training, which saw him winning two actual matches, and his method-style weight gain to play LaMotta in his later years as a down-at-heel nightclub owner/stand-up comic.

Awkward facial prosthetics aside, it’s an incredible performance, and Scorsese’s mastery of the form had never been more dazzling. Add in Michael Chapman’s stunning black-and-white cinematography, Thelma Schoonmaker’s Oscar-winning editing, and Joe Pesci as Jake’s brother Joey, and you have a film that’s easy to admire but incredibly hard to watch. The main problem? LaMotta himself.

A self-confessed wifebeater and rapist who once left a man for dead after attacking him with a lead pipe, LaMotta was a brawler famous for his ability to take hits from better fighters such as Sugar Ray Robinson, who he faced six times across a turbulent career. “I fought like I didn’t deserve to live,” he said. “I took unnecessary punishment when I was fighting. I didn’t realise it, but subconsciously I was trying to punish myself.” To which some might reply, simply, good.

When producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler visited the set, one of their team asked why they wanted to make a film about such a “cockroach”. While Scorsese considered it a valid question, De Niro leapt to LaMotta’s defence. But then he would—it was LaMotta, the film’s technical consultant, who was teaching him to box.

Cockroach or not, throughout the film, LaMotta is repeatedly compared to wildlife. His neighbour—whose dog he threatens to kill—calls him an “animal”. A mafia guy says he’s a “fucking gorilla”. And screeching noises flood the soundtrack when he’s in the ring.

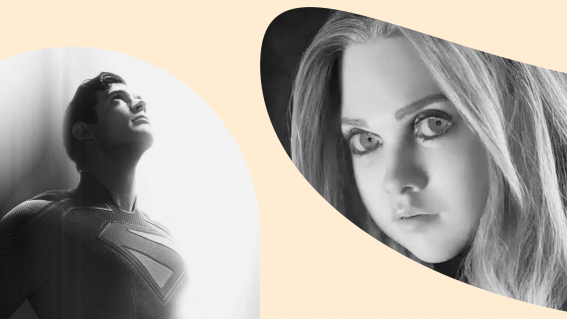

At home, we watch him brutalise his first wife, Irma (Lori-Ann Flax), then marry the teenaged Vickie (Cathy Moriarty, incandescent in her debut role), only to do the same to her across many, many years. LaMotta may be a champ in the ring, but at home, he’s a mess: riddled with jealousy and self-loathing and articulate only with his fists.

Contrary to how people remember it, Raging Bull is essentially 90 minutes of drawn-out domestic horror interspersed with 30 minutes of fighting. It’s a punishing split that makes the viewer, like LaMotta, long for the relief of being in the ring.

When these sequences come they are, rightly, considered some of the most striking ever shot.

Set to the Mascagni’s haunting Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana, the opening sees LaMotta, alone on the canvas, shadow-boxing himself. His loss to Jimmy Reeves has him punching straight to camera, attacking us, attacking everything, as smoke curls and flashbulbs explode. A pivotal match against pretty-boy Tony Janiro, the subject of much jealousy, plays out like an awful, slow-motion murder. And his final fight against Sugar Ray Robinson seems to take place in hell itself, with steam rising and hot blood spraying, as LaMotta, his face ruined, insists, “I never went down!” It’s a mantra that, in his personal life at least, will destroy him.

This is unforgettable stuff, but the question remains—why bother? Why turn a cockroach into a Christ figure, falling back against the ropes in a cruciform pose? Why use your artistic powers to explore the soul of a man who only caused pain? Who lost everything, learned nothing and went to jail (for pimping an underage girl) insisting, “I’m not an animal!”, when all the evidence points to the contrary.

Upon release, the film performed poorly, despite winning two of its eight Oscar nominations. Since then it has been recognised—rightly—as a major work by one of the best directors of all time. But anyone who’s experienced LaMotta’s particular brand of self-pitying male violence IRL might be tempted to say fuck him and fuck Raging Bull.

Perhaps the last word should go to Vickie LaMotta, the woman who suffered most at his hands. When she and Jake saw the finished film he, supposedly, broke down in tears, asking, “Was I really like that?” “No,” she replied, “you were worse.”