Memory is a ponderous drama with big things on its mind

Is there a difference between forgetting something, and not remembering it? Jessica Chastain and Peter Sarsgaard’s new film Memory will get you pondering big questions, writes Luke Buckmaster.

Can memory be understood in part through its absence? That idea sounds contradictory, given memory is an ability, or capacity, so closely associated with the act of recalling. But surely gaps and distortions inform our understanding of what we remember and why. Mexican writer/director Michel Franco’s elegently crafted new film gets you pondering these sorts of questions. While the drama is carefully calibrated, the film itself has a drifting quality that came, for me, after it concluded, in the thoughts swimming around my head.

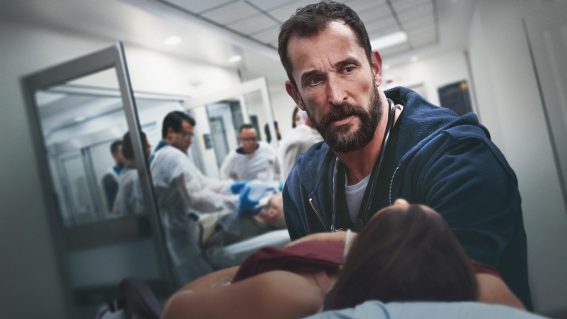

Its simple title, “Memory,” frames the film within a broad but clear thematic context, influencing how we interpret various aspects of the lives of its lead characters Sylvia (Jessica Chastain) and Saul (Peter Sarsgaard). The former is a social worker we first encounter during an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, where, instead of hearing about her trials and tribulations, we learn about her strengths and successes, shaking the demon drink and inspiring the rest of the group, who speak about her reverentially. Captured in close-ups filmed from the actors’ sides, they draw from deep within, in the spirit of a living wake: celebratory but melancholic.

From this moment forward, Franco maintains a tone of scratchy tenderness. Memory is big-hearted in some ways but unsettled and sad, as if, like its leads, burdened by the weight of the world.

Sylvia has some of this aura too. She’s wearied and wary, hopeful but wounded. If ever there was an anti-meetcute (a meet-ugly?) it would be her preliminary interaction with Saul, who sits next to Sylvia at her high school reunion—receiving a less than enthusiastic response—then follows her home, standing outside and staring into her windows. The audience are kept in the dark about what’s actually going on: there’s virtually no dialogue during these moments, and they’re staged clinically, without signposting danger or malice. It’s revealed that Saul—who Sylvia finds is still outside the next morning, cold and shivering—has dementia. He doesn’t remember leaving the party, and has no idea why he followed her.

This is a curious way to begin the drama, and the first in a series of revelations. Soon later Sylvia recounts to Saul how she was raped by an old high school friend of his, before accusing Saul of doing something terrible himself. This scene has an aching quality that speaks to the sheer unsolvability of life, the lack of neat edges. It’s a moment engineered to make a point that sometimes closure is impossible; Sault wouldn’t even be able to remember what he did, assuming Sylvia’s allegations are true. Initially there’s no reason to doubt her, but Franco will soon drop another bombshell to muddy the waters.

Each revelation triggers more questions, which are bound to vary between viewers; nothing is put in highlighter pen. Chastain and Sarsgaard’s performances are nudged into slightly different spaces as we begin to trust their characters in some ways and distrust them in others. This is an actor’s movie—not the kind you can cut around or save in the editing room—and you can feel the performances expand with the drama. None of it feels laboured.

The possibility that Sylvia got it wrong in relation to the aforemented accusation—and Saul is innocent—beckons the question of whething she should she apologise to him, even though he wouldn’t even remember being accused. Such questions feel totally germane to the drama, so much so that you forget Franco is making a series of calibrations, designed to have us interrogate his characters, in a soft sort of way.

Afterwards I wondered, is there an essential difference between forgetting something, and not remembering it? Or never forgetting something, and remembering it always? To say that Memory doesn’t come up with any firm conclusions would probably be stating the obvious. It’s the questions that are most important; the act of pondering.