The Last Dance proves Michael Jordan is a god, but does it live up to its reviews?

Netflix’s basketball documentary series explores the glory days of the Chicago Bulls, when a god known as Michael Jordan roamed the courts. Critic Luke Buckmaster dives in and wonders: will it deliver any dirt on the squeaky clean superstar?

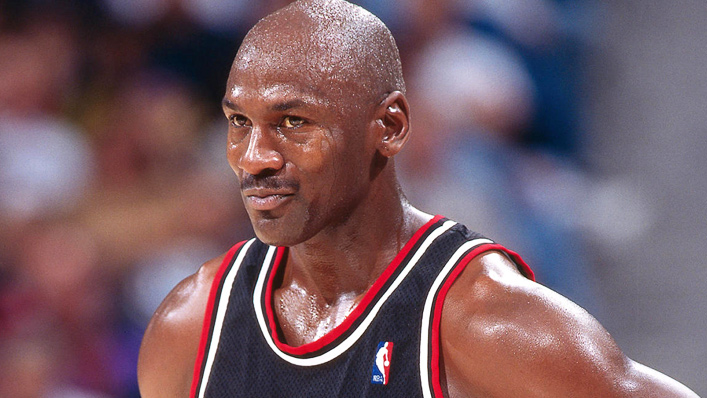

Back in the days when I followed the NBA my favourite player was Karl Malone; Michael Jordan was too obvious. At least I assume that was the logic of my young acne-smeared self, because you would have to be insane not to recognise that Jordan was the best player by a very wide margin—a fact reiterated by several players, including greats such as Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, in director Jason Hehir’s 10-part Netflix series The Last Dance. As a core framing device Hehir uses the Chicago Bulls’ 1997/1998 season, during which the basketball team with the then-coolest colour combination on earth (black, red, white) pursued a sixth championship.

See also

* All new movies & series on Netflix

* All new streaming movies & series

The big problem with Jordan was that he was always too good, too talented, too majestic. He was a god in human form: a relative of Zeus and Hercules, who swallowed a lightning bolt then descended from the clouds wearing synthetic herringbone traction pattern shoes, to play some bball, star in a dodgy 90s movie in which other characters, not he, were the aliens (the perfect cover) and collect sponsorship deals worth the annual GDP of some small nations. Jordan was so amazing the words of a cheesy song written for a Gatorade commercial accurately summed up the human race’s collective feelings: “I dream I move, I dream I groove, like Mike.”

Does the show live up to its reviews?

A quick look at the reviews of The Last Dance suggest the show has drawn the same kind of halo-ringed acclaim used to describe the mystical creature in jersey number 23. It is superb. It is enthralling. It is a pulsating celebration of greatness. It is intoxicating and stunningly refined. It is…

Yes, it is good. Very good. It is moreish and rollickingly paced, constructed with a fastidious largesse that attracts one to labels such as “exposé” and “procedural” to communicate the scope of it. A scope that is, paradoxically, limited in some respects, given Hehir is plainly uninterested in using basketball as a means to tell a larger story. This is not a series that holds the sport up as a mirror with which to reflect society, as Ezra Edelman did in the superb OJ: Made in America, using Simpson’s story as a way to pry open a broader discussion about race and fame.

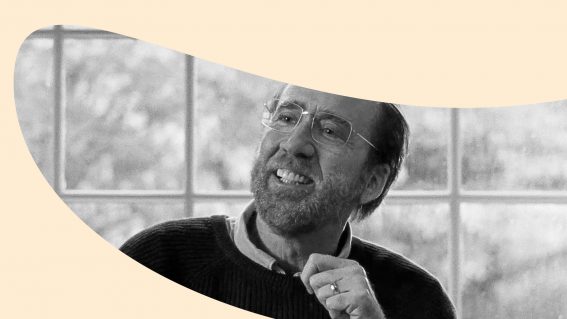

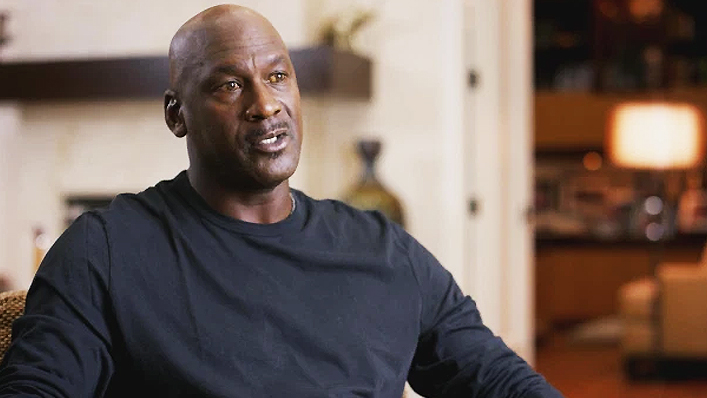

In present day interview scenes Jordan, with his big, heavy eyes, looks long-faced in an ambiguous sort of way, kind of mournful and kind of meditative. Is he unhappy to be here? Does Magic Mike (he had that moniker well before Channing Tatum paraded his pectorals) need a hug? Or is he just treating his responsibilities as an interviewee very seriously?

It has a treasure trove of unseen footage

Hehir has up his sleeve a treasure trove of previously unseen footage captured during the 90s. When the director deploys this footage (which is very often) the feeling of nostalgia that permeates the series assumes a literal quality, in the fuzzy low-fi look of the old recordings, which are immediately distinguishable from the crisp high definition of the current era.

I had heard on the radio that the reason the footage remained unused for so long, gathering dust in a vault somewhere, was because Jordan thought it might paint him in a negative light—showing him for example as shouty and domineering. But for a second I thought that might be the least of his problems. About 30 minutes into the first episode (this article encompasses the first two) Jordan is asked if he recalls a phenomenon known as the “Chicago Bulls traveling cocaine circus.” Now we’re talking!

The superstar, who has long cultivated a squeaky clean image but now has a glass of whiskey by his hand—an emergency drink for curly questions, perhaps—responds by laughing heartily. As if to say “oh yes, the good old days.” Have we finally got some dirt on Mike?

It kind of had to be a love-in

Alas, the champ recounts a story about how he entered a hotel room one night during the aforementioned circus and observed the existence of coke, weed and women—then promptly marched out the door. Shortly after reflecting on this moment an interviewee pops up to describe Jordan’s favourite beverages at the time: “orange juice and 7-Up.” Damn. The man really is a saint. Even that footage of him being shouty and demanding just makes the point that he was extremely dedicated, never settling for second best.

To some extent The Last Dance is a love-in; to some extent it was always going to be. Jordan “played every game as if it were his last,” says one interviewee, citing the same logic I apply to all-you-can-eat buffets—go in hard, go in fast, don’t expect your stomach to ever fully recover. Be like Mike (minus the ability to walk, let alone slamdunk). Adds another: “Jordan was the only player that could turn it on and off, and he never freakin’ turned it off.”

Hyperbolic language, to be sure, but again, not undeserved. Jordan was the greatest—but far from the only player to be blessed with sensational turns of phrase. Inspired by the series, I fished out my old Fleer folder full of basketball cards, encased in plastic pockets that hadn’t been touched for decades. I have six Michael Jordan cards and five Scottie Pippen cards. But I have 57 of Karl Malone. Want to know why they call him “The Mailman”? Because he always delivers.

But Malone, to the best of my knowledge, did not get a Gatorade commercial or a Looney Tunes movie. He did not cause every single human being on earth to turn their heads and say: that person, or saint, or celestial being, lives among us but is obviously from another world. Like Mike. We all wanted to be like Mike.