Netflix’s new show gets it wrong: Nurse Ratched was never a villain

Ratched is a gruesome origins story featuring a diabolical performance from Sarah Paulson. But, says critic Luke Buckmaster, the entire premise of the show is wrong—because Nurse Ratched was never a villain.

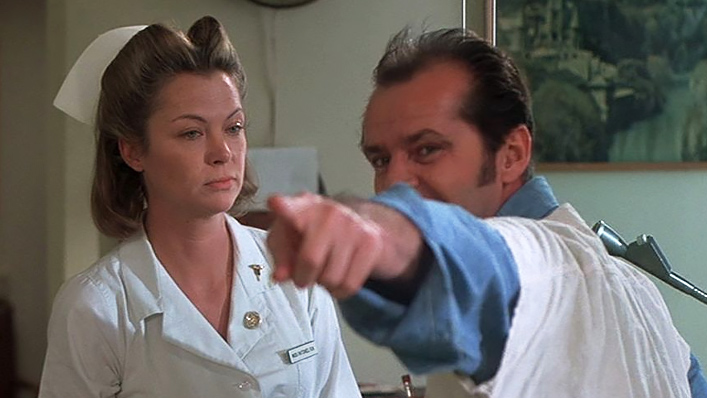

Ratched is a loud, pulpy, garishly stylish Netflix series with an intensely overripe colour scheme and a diabolical stink-eyed performance from Sarah Paulson. Created by megaproducer Ryan Murphy, whose oeuvre includes American Horror Story and Scream Queens, the show trades the narrative of a hell-raising rebel—Jack Nicholson’s famous character in the 1975 adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—for a Grand Guignol origins story about his nemesis, who in this icky reimagining appears to have crawled out of hell itself.

See also

* All new movies & series on Netflix Australia

* All new streaming movies & series

Set during the formative years of her career, the famous titular nurse—who originated in Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel and was unforgettably played by Louise Fletcher in Miloš Forman’s film—is seething and soigné. Nurse Ratched gets wrapped up in a range of B movie type incidents, including administering an icepick lobotomy and convincing a distraught man to commit suicide.

Paulson’s Ratched is evil with a capital “E”—declaring war when a colleague eats her peach and contemplating aloud “all the things I’m going to do about it,” with making friends and repairing the relationship not being examples of them. Paulson is cartoonishly cold, contrasting Fletcher’s chillingly realistic cold. This truly wicked version of the iconic character seems to be resonating with audiences, finding popularity worldwide and joining an expanding canon of super villain origin stories, from The Bates Motel to Hannibal Rising and Joker.

Except there’s just one problem: Mildred Ratched was never the villain. Or at the very, very least should not be viewed as the primary source of evil in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I say this knowing that Fletcher’s Oscar-winning performance landed at number five in a vote on the greatest all-time screen villains conducted by the American Film Institute, and that her character’s status as a supposed devil incarnate continues to be accepted as a matter of fact. Therefore the question beckons: who or what was the real villain?

Who or what was the real villain?

The short answer: a punitive, primitive, outdated and inhumane healthcare system. Ratched was a professional who kept her calm—and followed established practice—during very trying circumstances. Was she a likeable character? Good lord no. But calling her the villain is a convenient simplification that undermines a key message in the film (which is the basis of this piece, rather than Ken Kesey’s novel—though I read it many years ago) and embraces the idea that individuals are to blame for deep systemic failures. It also implies Ratched derived pleasure or satisfaction from doing the wrong thing. In the film, at least, she didn’t.

Murphy’s new series is probably best accepted in the spirit of a lurid fantasy for the midnight movie crowd. But, working from the view that the very premise of the show is wrong, perhaps it can help us rethink its predecessor—particularly when it comes to assigning guilt and the difficulties in ascertaining culpability. Because the long answer is: the originator of harm in this film isn’t just the system, but also the rabble rousing protagonist propelling its narrative. If people are wrong about accepting Ratched as an open-shut example of villainy, they are also wrong about bestowing upon Randle McMurphy the status of a hero, no matter how great his ‘screw the man’ counter-cultural appeal.

The careful routine governing the day-to-day life of the psychiatric hospital managed by Ratched is thrown into disarray upon the arrival of McMurphy, a non-conformist who is faking mental illness to get out of serving time on a prison farm. Nicholson (and those amazing eyebrows!) is so effective as a ‘likeable rascal’ that it’s easy to forget two important things. One: this man committed statutory rape of a 15-year-old girl. Two: his behaviour inside the hospital is selfish and reckless at best—and sometimes flat-out immoral.

McMurphy swindles cash from sick people

When he arrives, for instance, McMurphy is quick to set up a gambling ratchet, playing cards and fleecing money and cigarettes from fellow patients, all of whom are mentally unwell—some severely so. Stay classy, bud: swindle sick people out of their cash and belongings. When McMurphy steals a school bus and leads an escape mission, he takes the men on a fishing trip in the Pacific Ocean that might well have ended in disaster (and nearly does).

Worse, towards the end (do I have to write “spoiler alert” for a film that’s nearly 50 years old?!) the protagonist smuggles booze into the hospital one evening and the group get absolutely tanked. They even fill a catheter bag full of alcohol and pour it into the mouth of a profoundly ill man—a patient so unwell he cannot verbally communicate, let alone offer his consent. Who’s the villain now?

I am mentioning all this not to be a pro-establishment killjoy, but to provide a reasonable context with which we can view Ratched’s response. How does she handle these situations? Almost all of the time with an unflappably calm, steely and professional demeanor. During McMurphy’s many attempts to derail group counselling sessions, for example, the nurse keeps her cool. Sometimes—such as when Ratched discredits the results of a group vote to watch a football game, on the grounds that the meeting has been adjourned—her cold dismissiveness is infuriating.

The difference between being unethical and being a villain

But she is also being ambushed and undermined by somebody happy to destroy months or even years of work for his own pleasure and amusement. One session ends with McMurphy smashing the glass windows of the nurse’s office, then punching a security guard. After the all-night bender, he physically attacks Ratched. The catalyst for the attack is something Ratched said (“I wonder how your mother is going to take this”) to the young stuttering man Billy (Brad Dourif) that upsets him so much it acts a trigger for his suicide.

She knows this will penetrate Billy’s Achilles Heel and hurt him deeply. It was a terrible thing to say, spoken during the heat of the moment. This makes her behaviour unethical; it might even make her a bad person. But a villain?

No. The system is the villain. This becomes clear when we witness what the hospital does in response to McMurphy’s violent behaviour. In a word: lobotomy. After the smashed window incident, McMurphy receives a light dose of good ol’ fashioned electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). After attacking Ratched, he receives such a heavy amount that it turns him into a vegetable. It is outrageous to think ECT could ever have been used like this: to ‘cure’ somebody by making them braindead. And this person wasn’t even sick. The hospital board of directors knew McMurphy was almost certainly faking it and decided to keep him there anyway—a clear violation of their duty of care to the rest of the patients.

There is an ongoing debate about the effectiveness of ECT, with what appears to be growing consensus that its application has changed dramatically over the years and has come a long way “since earlier, darker days when it was known as electric shock therapy and conjured images from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Regardless of this debate, the hospital was wrong in its practices, even if it was informed by the science of the time.

Sarah Paulson’s double standard

Ratched did not kill McMurphy—the system did. Ratched did not kill Billy either. There is certainly a connection between bullying and suicidal thoughts, but that connection is complex and accusing somebody (who was trying to help, no less) of causing a death by suicide is problematic and usually unfair.

Given the cartoon nefariousness of Paulson’s performance in Ratched, I nearly fell off my chair when I read an interview with the actor, during which she addressed the ‘villain or not’ debate.

“I never saw her (Ratched) as a villain. I really didn’t,” Paulson said. “She’s a person in pursuit of absolution” (which means to be freed from guilt or blame).

So: absolution by way of….an ice pick hammered into somebody’s head? Oh please. If Paulson didn’t think she was playing a villain, her performance misses the mark so wildly the words “ill-judged” barely begin to cut it. The actor was surely trying to have it both ways: relishing in the wickedness of Ratched 2.0, while acknowledging after the fact that, indeed, the famous nurse was never really the villain.