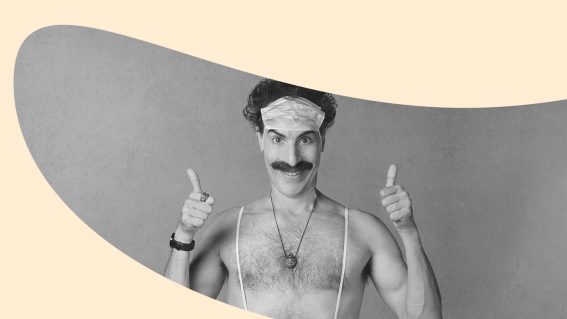

Peter Jackson interview: how I made the visually stunning They Shall Not Grow Old

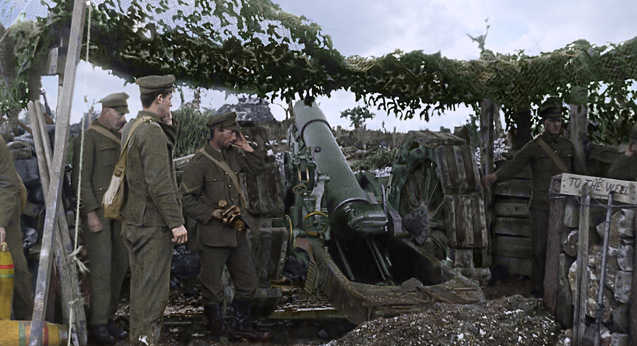

The latest production from blockbuster director Peter Jackson is They Shall Not Grow Old, an innovative World War I film that converts scratched old documentary footage into vibrantly coloured images.

To the mark the centenary of the war, the film is playing in Australian cinemas from November 11. Jackson, whose previous movies include The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit movies, sat down to talk to us about his striking new work.

How is your day of interviews going so far?

This is a movie I don’t mind talking about. The interviews are always interesting. It’s a topic that I’ve had a passion for since I was a kid. So I certainly can’t complain about having a day devoted to talking about the First World War. I’m certainly not going to complain about that!

For this visually striking film you converted an enormous amount of grainy black and white footage into richly coloured images. Tell us about that.

I’ve had a very fortunate experience. We had 100 hours of original footage sent to us by the IWM. Part of what I wanted to do, as a freebie for them, was restore everything. So even though we only use an hour and a half in the film, we restored the entire 100 hours. I said you send me the film and I’ll restore it for you, just to get their archive in better shape.

That led to me to decide that there shouldn’t be narration, there shouldn’t be anybody else talking – it should only be these guys, the guys in the war. The film was organic in that way. When I saw the restored footage that’s when I thought: let’s get into all the audio archive stuff and have the soundtrack composed entirely of them telling us their stories. I didn’t really know in the beginning what I was going to go. But the footage and the audience made it clear what the film should be.

You Shall Not Grow Old is a constant barrage of information. Were you worried about telling a story that didn’t have a protagonist and a conventional three act structure?

It’s a good question. We made a decision not to identify the soldiers as the film happened. There were so many of them that names would be popping up on the screen every time a voice appeared. In a way it became an anonymous and agnostic film. We also edited out any references to dates and places, because I didn’t want the movie to be about this day here or that day there. There’s hundreds of books about all that stuff. I wanted the film to be a human experience and be agnostic in that way.

We cleaned out any reference to particular times and places. But we made sure that everything we used in the film – out of 600 hours of audio that we had – we made sure it was all backed up by other people. I didn’t want to have one guy’s story about stealing the officer’s car and driving through town and yahooing. It’s a funny story if you hear it but it was only him that did that. I didn’t want individual stories about individuals. I wanted it to be what it ended up being: 120 men telling a single story. Which is: what was it like to be a British solider on the western front?

So in that regard it wasn’t a story film. It was a ‘tell us what it was like on the western front’ film. We had a very simple, start at the beginning and go through to the end of the war kind of structure. But it didn’t really need anything more than that. I found those men absolutely compelling.

The extensive oral history soundtrack of the film is very captivating. What was the logic behind relying so heavily on that?

I’m used to documentaries where there’s a narrator and a story. People obviously focus on the picture and the colour and the restoration. But I do like the fact that it is just the voices of the people who were there. To me it’s like, ‘let’s just hear it the way they experienced it’.

It’s amazing that, out of the 200 veterans we heard –we used 120 of them in the film – it is a very common story. They all ate the same food, for example. You have a lot of guys telling you essentially the same information in different ways. We would cut between them – picking the ones who did it in a funny way, or a poignant way. But they all had the same story.

This is a film of great technical innovation. It arrives at a time of increased use of emerging platforms such as virtual reality films. What are your thoughts about VR narrative films?

I’ve never really been a huge advocate of VR. I think that AR – augmented reality – is going to become a world-changing thing. Literally a world changing thing on the level that the first laptop computers were. In the next two or three years that’s the thing I am most excited about – where you’re taking the real world and adding things to it.

But the idea of putting these headsets on, and cutting yourself off from everyone else, and being in this place – where the image is low res, and all pixelly – I think it’s fine possibly for theme parks or museums or games maybe. There will certainly be uses for VR. But I think the really exciting thing is AR.