Pulling the Strings: Rick Baker’s Best

Stan Winston. Dick Smith. Tom Savini. Rob Bottin. There’s a reason why these names are recognisable to you movie geeks out there. It’s because they’re artists. Undisputed masters of the special effects makeup field. These guys are responsible for some of the most unforgettable, influential scenes and creations in cinema. Today you’d be hard-pressed to […]

Stan Winston. Dick Smith. Tom Savini. Rob Bottin. There’s a reason why these names are recognisable to you movie geeks out there. It’s because they’re artists. Undisputed masters of the special effects makeup field. These guys are responsible for some of the most unforgettable, influential scenes and creations in cinema.

Today you’d be hard-pressed to reel off a similar list of names for digital effects. Who are the rock stars of contemporary CGI? WETA? Yep — just large companies who employ hundreds of anonymous drones to click copy + paste all day. I’m exaggerating of course, and yes I know, CGI can be a fantastic, brilliantly useful tool. But what the current over-reliance on digital effects means is that the painstaking artistry of these seasoned craftsmen is a thing of the past.

The most recent casualty of this “industry standard” is Rick Baker, who announced last month that he would be retiring. “I like to do things right, and they wanted cheap and fast,” he said. “That is not what I want to do, so I just decided it is basically time to get out.” For the 64-year-old makeup artist — who’s worked on everything from Star Wars to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” music video to Men in Black — to throw his hands up, as if in defeat, is a bummer for fans of practical effects (and ironic too, given the current spotlight around the non-CGI effects work of Mad Max: Fury Road).

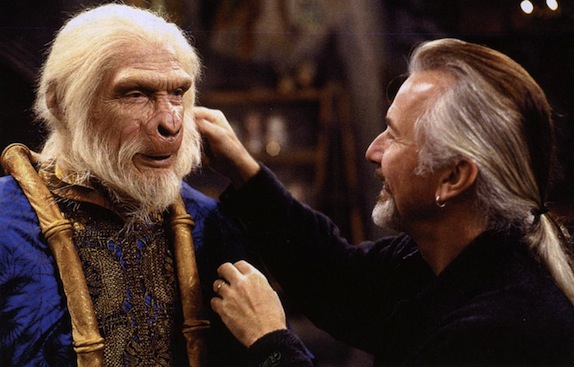

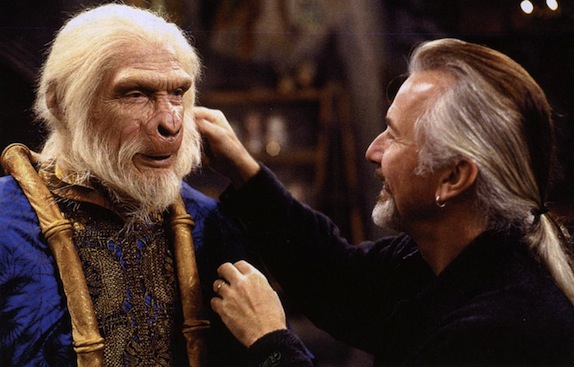

Baker’s achievements are wide-ranging and consistently stellar, even in abysmal movies like Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes remake. But here are five films he worked on that I’d consider both as favourites and key to appreciating his art…

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON

Baker would return to the werewolf several times in his career (the short-lived TV series Werewolf, Wolf, The Wolfman), thanks to his ground-breaking work on John Landis’ enduring 1981 horror-comedy classic An American Werewolf in London. Brought to life by 30 technicians over a torturous 6-day shoot, the sequence in which star David Naughton first metamorphoses into the hairy beast of the title lavished Baker with attention (he received his first Oscar) and holds up astonishingly well today. It still looks bloody agonising. The hair growth. The stretching of the limbs and torso. The sprouting of the snout. Baker told Naughton, “I feel sorry for you”, and you can see why all up there on screen. Griffin Dunne’s deep facial and jugular gashes are pretty good too.

VIDEODROME

David Cronenberg’s staggeringly prescient 1983 sci-fi horror masterpiece Videodrome is still perhaps Baker’s most unusual project to date. For a tale that posits how images can alter the mind and body, it’s only fitting that the effects would too convey an intense, organic physicality. It’s the perfect marriage of form and content. CGI, a non-tactile discipline, would not have been as effective. Despite a tight budget and schedule, Cronenberg gave Baker plenty of freedom to come up with what would eventually become iconic imagery in the Canadian auteur’s filmography: throbbing videotapes, vein-popping television sets, the “cancer gun”, the vaginal cavity in James Woods’ stomach. Absolutely visceral stuff all round, a major contribution to the film’s hallucinatory vibe.

HARRY AND THE HENDERSONS

This goofy family-friendly take on Bigfoot may not be a particularly great movie, but of all his designs, Baker has called Harry his “proudest”. It’s an interesting word, in that it speaks to practical effects as a process almost akin to giving birth to a baby. It’s easier to be emotionally invested in a character you’ve created when you can actually see it in the flesh. Likewise, the three-dimensional presence has an immediacy that helps communicate Harry’s endearing personality to the actors, who have something real to play off on set rather than a green screen nothing that’ll be filled in later. Predator actor Kevin Peter Hall, who donned the Harry suit, is blessed with expressive eyes, but Baker and his team add spectacular dimension to the creature with their skillful, radio-controlled lip-and-brow movements. Another Oscar winner.

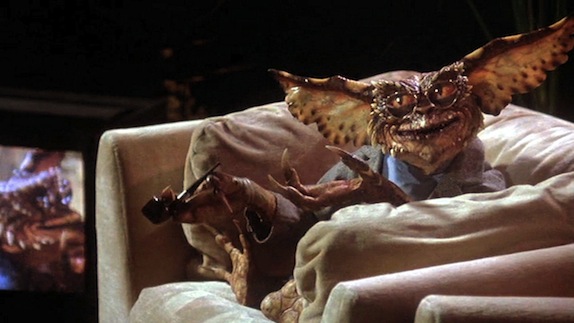

GREMLINS 2: THE NEW BATCH

Baker initially turned down the offer to work on this, seeing as he wasn’t the creatures’ original creator, but came on board when writer/director Joe Dante said he could design a whole bunch of new gremlins. And many new gremlins there were. Mutant spider gremlins, bat gremlins, a brain-hormone-enhanced gremlin, a gremlin bride. It looked like Baker had a blast making this, pulling out all the stops in the goo department. The thing that strikes me about Gremlins 2 now — other than the fact that Dante made of the most deranged sequels of all time — is that when you see the hundreds of rubber latex gremlins packing the frame during the climax, it’s a hell of a lot more impressive than those large scale CGI battle/disaster scenes that are the norm for modern blockbusters.

ED WOOD

There’s something moving and beautifully personal about Baker’s transformation of Martin Landau into Bela Lugosi for Tim Burton’s affectionate biopic of legendary bad film director Ed Wood. As a child who grew up idolising Jack Pierce, the makeup artist best known for his work on the classic Universal monster movies, Baker considered this job a labor of love he would’ve worked on for free. Landau’s performance is an uncanny delight, and Baker’s subtle facial augmentations — larger ears, a cleft chin, bushy eyebrows — no doubt emboldened the actor to deliver the best portrayal of Lugosi he could. A rare example of ageing make-up that isn’t too overdone and looks just “right”.