Remembering The Animatrix: the Matrix spin-off that pays tribute to the franchise’s genre roots

The Matrix turns 20 years old this month. Zillions of articles will explore the film’s cultural legacy, so critic Travis Johnson instead revisits the unusual 2003 anthology film The Animatrix – which uses animation to explore The Matrix universe.

It’s kind of wild that The Matrix is 20 years old, isn’t it? Easily the most important cyberpunk film this side of Blade Runner, Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s post-modern kung-fu sci-fi actioner really knocked a hole through audiences back in 1999. And if the sequels didn’t quite manage to stick the landing, the original still stands as an epochal film.

But The Matrix wasn’t just a movie trilogy. The Wachowskis didn’t want to confine their creation to one screen – they wanted their worked to fill every screen, giving us a multi-media modern myth for the millennium. There were computer games, of course, as well as comics, but the most high profile franchise spin-off was The Animatrix, a short film anthology released just prior to The Matrix Reloaded in 2003.

Comprised of nine short films from a variety of predominantly Japanese animation houses, The Animatrix was unusual at the time, but ushered in a short run of similar animated efforts to flesh out the settings of blockbuster genre films. Universal got in on the act in 2004 with Van Helsing: The London Assignment, expanding the ill-fated Hugh Jackman supernatural actioner, and The Chronicles of Riddick: Dark Athena, a further adventure of Vin Diesel’s space barbarian. Matrix studio Warner Bros. returned to the idea in 2008 with Batman: Gotham Knight, to bridge the gap between Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

However, The Animatrix stands above and apart from the films that followed for a few reasons. Using animation to explore The Matrix universe is tonally and stylistically appropriate, for one thing. Anime is an acknowledged influence on both The Matrix’s look and the rhythm of its action sequences, with Momoru Oshii’s 1995 film Ghost in the Shell not only specifically namechecked by the creators, but actually included in a Matrix-themed “Anime Classics” box set, along with Akira and Ninja Scroll, shortly after The Animatrix was released.

For another, the very idea of The Animatrix was an unusual prospect back before we got used to the idea of following a sprawling, interlinked saga across different platforms, ala the Marvel Cinematic Universe. When the first The Matrix film hit in 1999 it really blew the doors off film culture. You must remember, the big sci-fi movie that year was supposed to be Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. Then along comes this ballsy sci-fi actioner from an almost unknown sibling director team, starring walking punchline Keanu Reeves and Aussie character actor Hugo Weaving, and it was wilder, cooler, more of the moment and more straight-up audacious than the accepted canon.

It was groundbreaking, pure and simple. Not only were the Wachowskis building a whole, epic sci-fi trilogy, but their world was so big, their ideas so intricate, that they would spill the banks of cinema and need other forms to contain them. Of course, we hadn’t seen The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions then, so enthusiasm for the franchise hadn’t been tempered by the fact that the subsequent instalments weren’t all that.

And so, The Animatrix, which debuted less than a month after Reloaded’s theatrical bow. Like all anthology films, The Animatrix is a bit of a mixed bag. The centerpiece short, the CGI animated The Final Flight of the Osiris, has aged worse than any other segment, owing to the continually evolving nature of computer-generated effects. Set immediately before The Matrix Reloaded, the short sees two martial artists flirt-fighting in a virtual reality dojo, playfully slicing off each other’s clothes, before reverting to the real world for a desperate chase-fight against The Matrix franchises’ ubiquitous robo-squid sentinels.

At the time the animation quality was bleeding edge and the film knows it, lingering lovingly on different textures and reveling in fluid virtual camera moves. At this point, though, it’s on par with any number of computer game cut scenes, but the story conveyed, a lead-in to the feature sequel, seems forced. On first taste, however, this was really impressive stuff. Using complete CGI to render The Matrix’s signature arts fights and post-apocalyptic action was on point.

The other big ticket items, Second Renaissance parts 1 and 2, also suffer from the sense that they’re not all that essential, being basically animated lectures of the history of The Matrix universe, mapping out the early 21st century rise of artificial intelligence and dot-pointing the key events leading up to the current status quo (robots rule the world, people are asleep in pods, and cyberpunk rebels fight a running resistance in the virtual and real worlds, in case you’ve been napping. These two boast some striking animation from Mahiro Maeda (Kill Bill Volume One) that repurposes historical imagery from real world revolutions and riots to tell its tale of robot rebellion, but the cardinal rule of showing instead of telling is well and truly broken.

The Animatrix fares much better when it’s taking little side trips into the world of the films and exploring the edges of the setting. Kōji Morimoto’s Beyond follows a teenage girl looking for her missing cat who discovers a supposedly haunted house where the physical laws of The Matrix simulation are glitching, allowing for seemingly supernatural phenomena.

Meanwhile Takeshi Koike’s World Record sees an elite athlete push through the film’s simulated reality through the sheer effort he puts into running, and Shinichirō Watanabe’s (Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo) Kid’s Story melds the notion of teen angst with the film world’s idea of simulated reality to give us a lonely boy who discovers his youthful alienation is really him clueing into the false nature of the world. All three offer tantalizing glimpses of the sheer imaginative possibility inherent in the film’s series’ conceit but stop short of giving concrete answers.

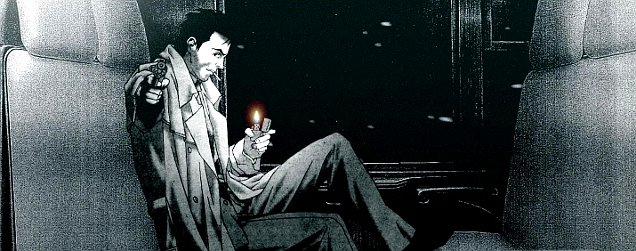

Of course, concrete answers aren’t necessarily The Matrix’s strongest suite (remember The Architect’s speech?), but it sure does have style. Out of a field of excellent and diverse animation styles, Yoshiaki Kawajiri (Ninja Scroll) delivers the most striking entry with Program, which largely takes place in a computer simulation of feudal Japan and gives us a beautifully colourful and kinetic horseback battle between a white-haired female warrior and her red demon-masked opponent/friend. Conversely, Shinichirō Watanabe takes us in a desaturated, monochrome direction for A Detective Story, which gives us a Sam Spade-ish P.I. whose world is turned upside down when he brushes up against The Matrix conspiracy.

Still, the best of the bunch is Matriculated, directed by Aeon Flux creator Peter Chung. Matriculated cleverly inverts The Matrix’s central conceit by having human operatives capture robot soldiers and insert them into a small simulation of their design, an attempt to win the robots to the human cause. Told with Chung’s trademark visual brio and exaggerated character designs, it’s a perfect melding of concept and style.

Sixteen years on, The Animatrix is a fascinating curate’s egg – an artefact from a time when its franchise forebear was shaping up to be a total world beater. That never quite happened, and the world is probably worse off for it, but the Wachowskis’ animated experiment remains, a missive from an alternate reality where The Matrix reigns supreme.