Retrospective: 25 years ago, Event Horizon made space exploration look like a terrible idea

The poster for 1997 sci-fi horror Event Horizon promised “infinite space, infinite terror”. It still conjures those cosmic ideas today, with creepy eyeless ghosts and religious themes, writes Eliza Janssen.

I got into an argument with my partner while watching Event Horizon. It was all about whether humanity’s exploration of outer space was a necessary mission to enrich and explain our existence, or just dick-measuring anthropocentric arrogance. I can’t really explain why I fall into the cynical latter category these days. Perhaps too many years of boring billionaires trying to turn the vast possibilities of our universe and solar system into capital for the elite?

Or maybe Paul W.S. Anderson’s sci-fi horror Event Horizon just had a corrosive impact upon me at a young age. The 1997 film chews up Star Trek’s utopian themes of galactic progress and spits ‘em out into the unending void of space, suggesting humans will just discover nihilism and our own fleshy trauma wherever we venture.

Celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, the movie begins in typically optimistic sci-fi fashion, with title cards explaining that, amongst other milestones, the first moon colony was established in 2015 (I must’ve missed that, seems like kinda big news). In the “present day” of 2047, Laurence Fishburne captains a rescue vessel sent to Neptune’s orbit, where the titular spaceship has somehow reappeared after being totally off the radar for seven years.

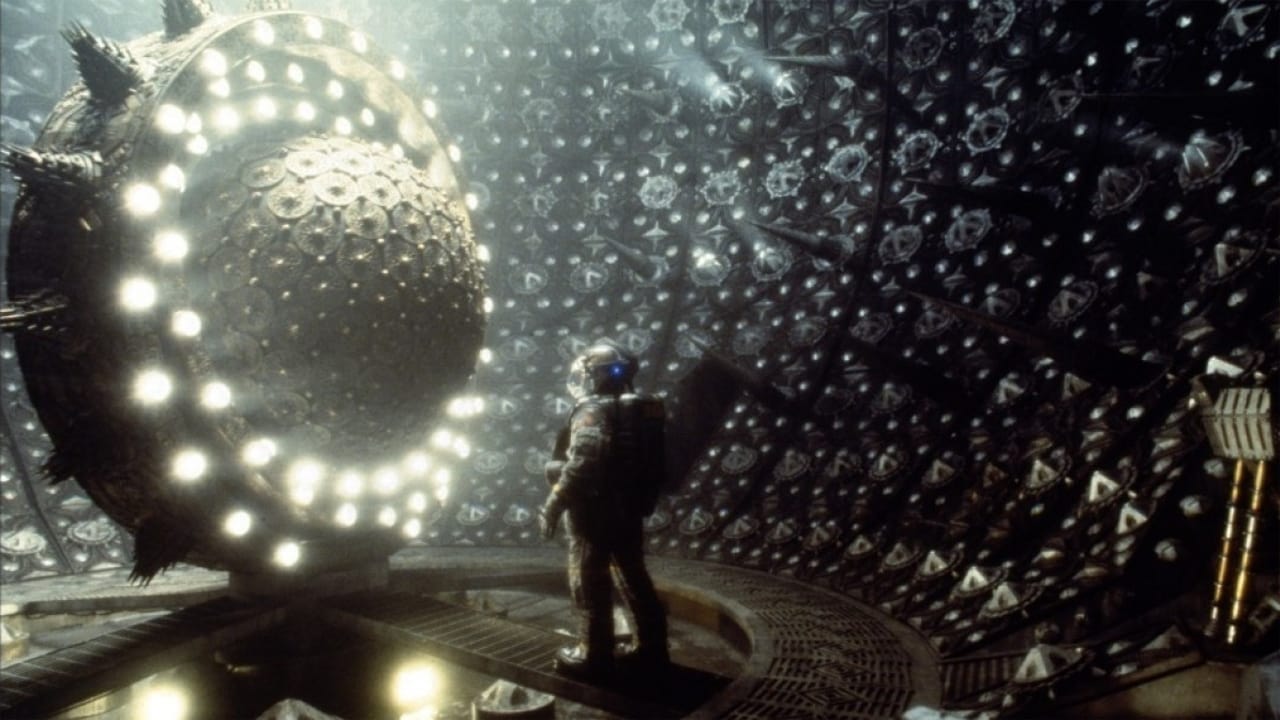

The Event Horizon itself looks like a big crucifix, and the gravity drive Sam Neill’s Doctor Weir designed for the ship’s bowels looks like some biblical angel wrought in studded iron—an ophanim, to be more precise. We don’t need to be well-versed in the events of Alien or Sunshine to know that the rescuers will soon be needing some salvation themselves, but these troubling production design decisions lay out early on that the evils of Event Horizon are far more spiritual than any hungry alien baddie lying in wait.

The first dread-inducing decision of the film is to never give us any sense of status quo on earth: it’s only seen in one quick video Peters (Kathleen Quinlan) watches of her sick son back home, who is destined to show up as a ghostly vision onboard. We begin and end in the dark canvas of deep space, where it’s always night, and our sole, weak comic relief comes from Richard T. Jones’ poorly-written goofball technician. Throw in some ominous screamed Latin in the abandoned vessel’s log, translated by Jason Isaac’s trauma doc in one trembling close-up scene, and you know these characters don’t have a chance in Space Hell.

The small crew is so doomed, in fact, that the driving action of the movie’s plot can feel unnecessary at times. There’s a lot of rushing back and forth on both ships, opening doors, closing doors, setting countdown timers…but it’s worthwhile for scenes such as the corrupted engineer Justin’s (Jack Noseworthy) attempted suicide via airlock decompression. He’s not doing so hot after looking deep into the void of Neill’s black hole drive, murmuring about “the dark inside me from the other place” before his veins become embossed deep on his arms and blood pours out of his eyes and through his fingers, droplets spinning in glorious zero-G.

Most horrifyingly of all, Justin seemingly snaps back to cruel clarity before experiencing the effects of his own actions. He’s been animated and cursed by the autonomy to end himself while understanding exactly how much it’s going to hurt—a scene that’s so agonising since it exploits “the dark inside”. Same goes for the guilty hallucinations our main characters see of the people they’ve wronged in life. Wherever we go and whatever technological marvels we try to shield ourselves behind, our fleshy, fearful insides are always vulnerable, and they’re simply not meant to handle the sheer nihilism of oblivion.

The fact that there’s missing footage of the film’s gory “hell scenes”, removed after it disgusted censors and test screenings, only furthers the cosmic horror ideas at play in Event Horizon. Seeing is believing, as any Disney movie will tell you, and the crew of Anderson’s “haunted house in space” are seeing a psyche-destroying blend of science and religion’s most troubling concepts. There’s a lot of mentions of hell in the film’s dialogue, but the film never specifies whether the Event Horizon has indeed returned from our ancient, biblical conception of a dark afterlife or just some dimension that looks pretty dang hellish.

While not a perfect horror or sci-fi movie by any means, Event Horizon nails the big scary perspective it brings to both genres. It takes a page outta Lovecraft’s book by making a monster that’s all the more awful because it doesn’t destroy us for any particular reason—for shits and gigs, maybe?

For me it’s that nothingness, the infinity that gets ya—both a believer’s worst fear that there’s no god or order waiting for us, and an astronaut’s anxiety of losing grip and spinning out into an endless void of terror. No rescue, no meaning: just eternal damnation. On second thoughts, maybe Elon Musk should invest in a black hole vacation sometime soon…