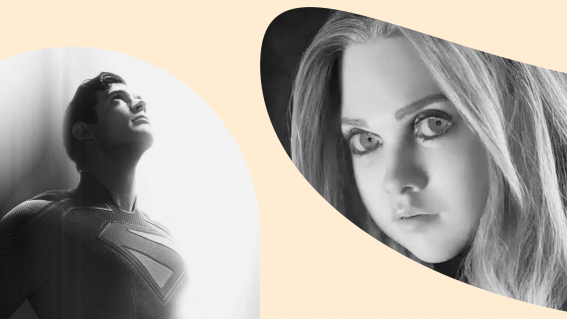

Retrospective: Peeping Tom probes the relationship between audiences, filmmakers and subjects

63 years after its controversial release, Michael Powell’s classic psychosexual thriller Peeping Tom has been restored in 4K for a new generation of cinema lovers to discover. Enter if you dare, says Lillian Crawford.

In her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws (1992), theorist Carol J. Clover defines the ‘assaultive gaze’ in horror films as masculine, while the ‘reactive gaze’ is feminine. That is to say that when we look with the villain, like in the opening sequence of Halloween (1978), we are attacking someone, usually a woman, whereas when the camera is positioned with a female character, we are the ones being attacked. This shifting dynamic is central to Peeping Tom, Michael Powell’s 1960 psychosexual thriller which pushed the limits of British taste so far that it effectively saw him exiled from the UK film industry. While Clover’s idea of an ‘assaultive gaze’ in most films refers to the human eye, in Peeping Tom the assaults are literally carried out by the camera itself, owned by Mark (Karlheinz Böhm).

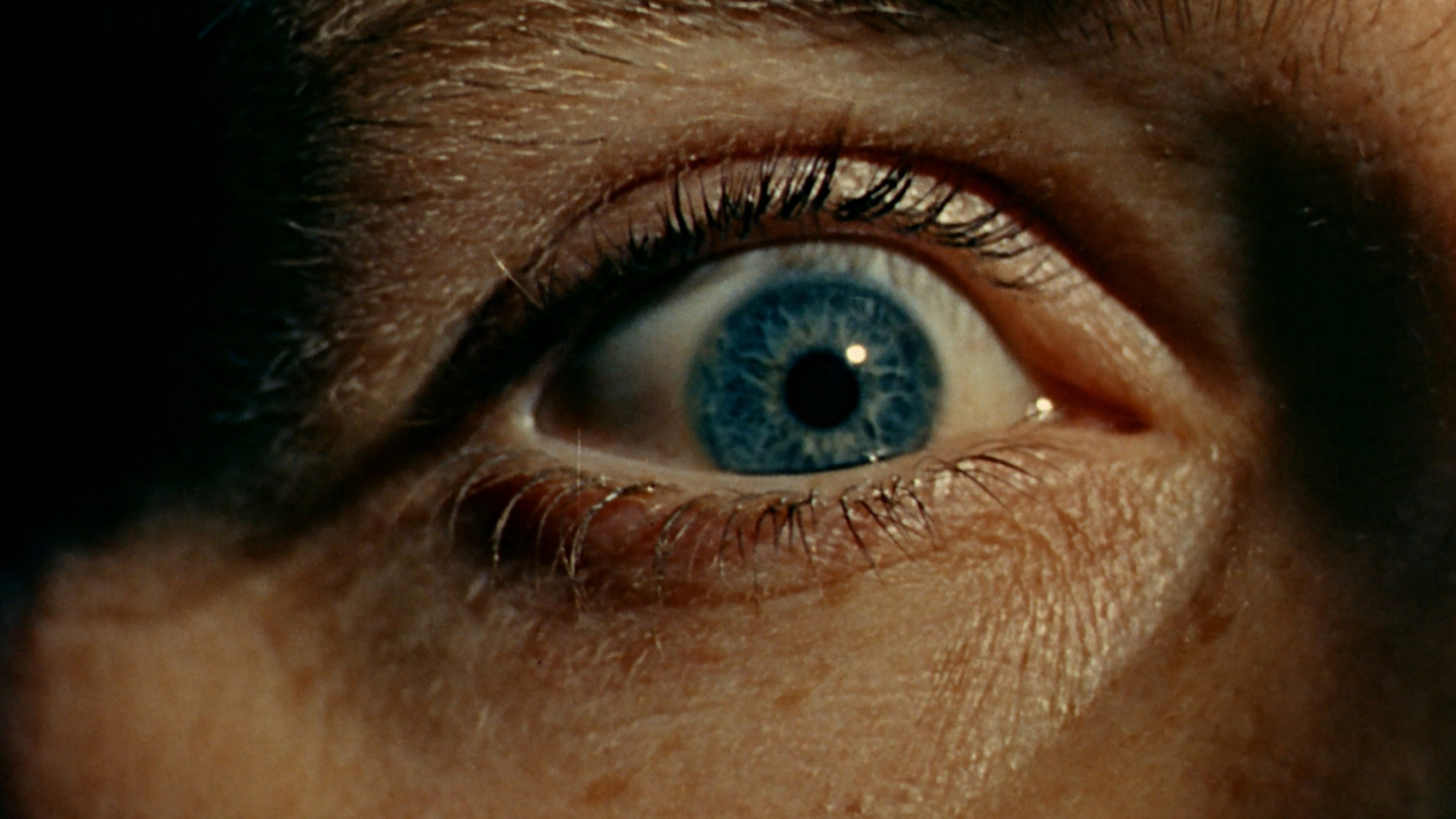

The opening scene moves from the famous bullseye of The Archers’ logo to an extreme close-up of Mark’s eye. We then watch a sex worker standing in front of a shop window filled with parts of female mannequins—dissected fetish objects. Mark follows the woman to her room, all the while shot from the camera’s perspective without ever looking from that of the woman. As she undresses, the camera gets closer, and the woman’s face becomes horrified, as the sound of celluloid running through a projector thrums into life. As we learn later in the film, the camera was given to Mark by his father, seen in footage shot during Mark’s childhood… a father played by Michael Powell himself.

Powell was obsessed with red-haired women. There’s Deborah Kerr in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and Black Narcissus (1947), and Moira Shearer in The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951). Even dark-haired Ludmilla Tchèrina dyes her hair red for the ball scene in Oh… Rosalinda!! (1955).

The visual motif of flaming locks parallels Hitchcock’s interchangeable stream of blondes. Theorist Laura Mulvey writes in Afterimages that Kim Novak’s icy hair in Vertigo (1958) “effectively deflects the gaze from the site of castration anxiety” and hides “the uncanny body of the mother”, thus the male voyeur constructs “the fabricated woman who originated in the myth of Pandora and leads to fantasies of, and experiments with, automata.”

In other words, it is the Freudian obsession with hair as a fetish object which drives men like Hitchcock and Powell to making films, to capturing women on camera and thereby being able to hold them in their hands like automata, mechanical dolls, and control them.

In Vertigo, when Scottie (James Stewart) believes the woman he loves, Madeleine (Kim Novak), is dead, he alters the appearance of Judy (also Novak) to reconstruct his ideal woman. He treats Judy as a doll, or fetish object, which he dresses and dyes blonde until Madeleine appears before him, spectral in the green light of her bedroom.

After working with Moira Shearer on The Red Shoes, Powell cast her again in Peeping Tom as a dancing redhead who is murdered by Mark with his phallic camera tripod leg. The film’s music, a piano motif consisting of rising and falling staccato notes written by Brian Easdale is reminiscent of his own ‘Dance of the Red Shoes’, heard whenever the camera or the projector is in motion. Powell, like Scottie, reconstructs his ideal film with its female lead in Peeping Tom which, like Scottie’s obsession with Judy, drives her to death yet again.

Mark sets up his camera to do a test, and Shearer starts to dance across the studio floor as he watches her through the camera. We watch her, caught in the cross section of the viewfinder not dissimilar to that of a sniper rifle. We are struck by the dual desire of Mark, as Powell’s double—both to kill and to fuck her. The relationship between Powell and Shearer when they made The Red Shoes had been fraught, with both going on to talk about the difficulties they faced during production. There is a sinister air of wish fulfillment as Mark murders Shearer, albeit with a knowing self-criticism which runs throughout Peeping Tom.

The other important redhead in Peeping Tom is Anna Massey as Mark’s tenant, Helen. When Mark first talks to her, she comes up to his room and knocks on the door, offering a slice of birthday cake with a candle as a peace offering. She convinces him to allow her into his inner sanctum, his development room and personal cinema, all the while Mark is anxious of how she will react when she sees the contents of the films—his father’s experiments on him as a child, and Mark’s own footage of murdered women.

It is structured like a macabre fairytale, specifically Charles Perrault’s Bluebeard in which the terrible duke marries a woman named Judith. He warns her not to enter a door in his castle, and when she does she discovers the bodies of Bluebeard’s dead ex-wives and is also killed. In 1963 Powell himself directed a film of the opera Bluebeard’s Castle in Germany, an adaption of the opera by Béla Bartók and Béla Balázs. There is a direct parallel between Helen standing in Mark’s doorway and Judith entering Bluebeard’s domain, where in Peeping Tom Mark’s celluloid corpses replicate Bluebeard’s dead wives.

Mark only ever touches the camera, and never Helen, or any other woman. He acknowledges that he has a problem, and at one point discusses the nature of voyeurism, or scopophilia, or being a ‘peeping tom’ with a Freudian psychiatrist. His own reckoning with his fetishism and desires, and how they intersect with his love of cinema, are aligned deliberately by Powell as a form of self-reflection. Not that, we hope, Powell was murdering his lead actresses.

But as obvious as the phallic metaphor of the camera might be, it is extraordinary to see a director confront his perspective and interests so directly, just as Hitchock did in Vertigo, and inspired filmmakers including Brian de Palma in films like Body Double (1984). 63 years later, and with a new 4K restoration just released, it continues to probe the relationship between audiences, filmmakers, and their subjects. Enter if you dare.