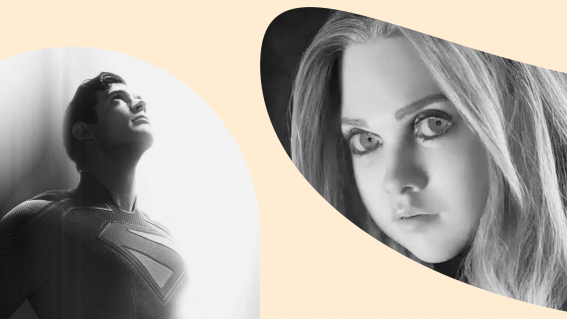

Revisiting Ridley Scott’s stunning 1977 debut The Duellists

As Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel makes its way to cinemas, Tony Stamp reexamines Scott’s similarly-titled, incredibly strong 1977 debut The Duellists.

Ridley Scott is 83 years old. He’s also a workaholic. It’s tempting to apply a sense of finality to the release of his upcoming film The Last Duel: his first, released in 1977, was called The Duellists. Both films are set in France. Both involve duels. This new one has the word ‘last’ in the title. But while it would be a poetic way to bow out, Scott being Scott, he has another one (House of Gucci) coming out in *checks notes* just over a month?!

The Last Duel had a reported budget of $100 million US (not counting marketing), and sports a handful of big stars, but The Duellists was a much more humble affair—not that you’d necessarily know that to look at it. Scott made his name as a sumptuous visual stylist, a descriptor that’s remained true through his career, and while his debut had a mere US$900,000 budget, he clearly made the most of every penny, delivering a film full of sweeping vistas, morning mists and setting suns, employing camera angles to turn a dozen extras into something that feels much grander, and making the most of existing structures. I’m sure this ingenuity didn’t hurt him booking Alien and Blade Runner in the years to come.

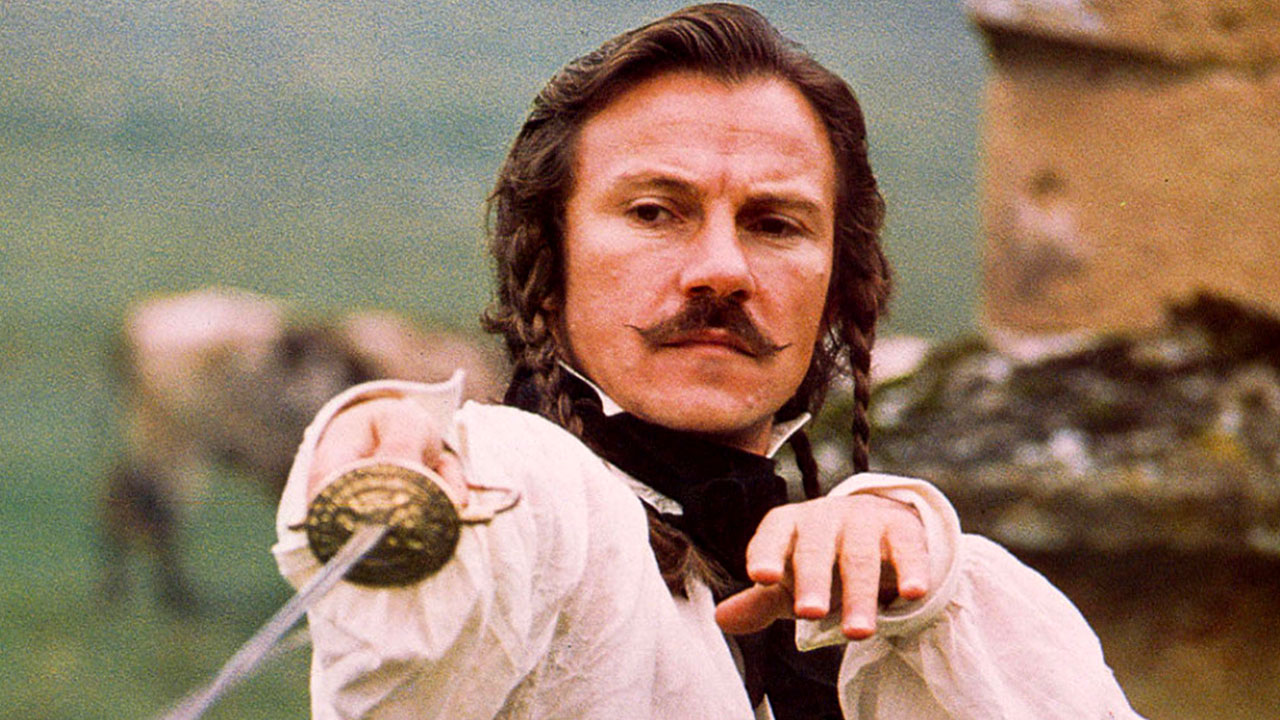

The Duellists is based on a short story by Joseph Conrad, itself a version of a true tale. Gabriel Feraud, a lieutenant in the French Army, is placed under house arrest for wounding the mayor of Strasbourg’s nephew. The officer sent to do the honours, Armand d’Hubert, inadvertently insults Feraud’s honour, and this sets into motion a series of duels between the men that will last for fifteen years (in reality the first happened in 1794 – Scott and his team adjusted the timeline to fit alongside the Napoleonic Wars).

Paramount Pictures gave Scott four choices for his lead actors in exchange for financing. He chose Keith Carradine, who a few years prior had won both the Oscar and Golden Globe for his original song ‘I’m Easy’ from Robert Altman’s Nashville, and Harvey Keitel, who’d recently spent a week acting in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now before his part was recast with Martin Sheen.

Carradine’s d’Hubert is a man whose pride is constantly being wounded, even in the moments he bests Keitel. Sometimes he seems terrified of Feraud, sometimes comedically annoyed. This is conveyed in the moments expression bursts through an otherwise buttoned-down facade. He’s the butt of the film’s joke in some ways, and I think Scott considers him something of a prig, but he’s also granted romance and a happy ending of sorts at the film’s conclusion.

Keitel, meanwhile, is a force to be reckoned with, Feraud’s inferiority complex and bloodlust making itself known through his frequently wide and wild eyes. He’s referred to as insane, and a brute, but it’s hard not to feel some sympathy for him as a man of lesser stock, a former peasant who fought to get where he is and who constantly feels the need to prove himself—when we meet him he’s literally mid-duel, and seems to regard this highly formalised system of stabbing or shooting another man as appropriate recourse to the slightest insult.

This is the film’s great irony. The two men slice and fire and cut, wounding each other to varying degrees each time, but their fights are constantly stymied by the conduct of the era; the ritual and rules of the duel. Their encounters become a self-sustaining engine of grievance as they literally take chunks off each other year by year. At one point they’re forced to march side by side as Napoleon attempts to invade Russia. Covered in furs and frost the two men fend off a handful of attacking forces, before d’Hubert turns to Feraud and simply says “Pistols next time”. Scott presents all this in his usual po-faced manner, and lets the absurdity speak for itself.

A few years prior, Stanley Kubrick had made Barry Lyndon, a film also set in the 1700s that used a similarly removed perspective to highlight the period’s silliness. Scott has spoken about the influence it had on him, and how he attempted to mimic its photography (styled to resemble paintings of the era), using natural light and composing long intricate takes. He did this for a tenth of Kubrick’s budget, and the results are stunning. The two men face off in front of rolling fields and distant herds of animals. The camera drifts out a window to reveal the inhabitants of a castle going about their business in adjacent rooms. Candlelit interiors are burnished and muted.

On its release the film was reviewed in the New York Times, who said it “may well remain one of the most dazzling visual experiences throughout all of 1978”, going on to rave “what one carries away from the film is a memory of almost indescribable beauty”.

At this point Scott had made thousands of commercials, and his gorgeous images are what has defined his career . A frequent criticism is that he allows them to overpower the substance of his stories, and The Duellists is clearly made by the same guy who helmed Legend and Blade Runner, content to let the pace sag as we soak up all the eye candy on offer. That said, it only runs for one hour forty, and is helped by its structure, essentially cutting from one duel to the next.

The film’s conclusion is beautiful not just visually, but also poetically. The final duel takes place atop a hill in the ruins of a castle, and eventually mirrors Napoleon’s downfall with Feraud’s as he’s left to simmer, stymied by the same societal rules that allowed him his ongoing vengeance. Scott makes this clear by mirroring an 1830 picture of Napoleon by British painter Benjamin Robert Haydon. The sun emerges from the clouds, shining down on Feraud as he’s left with no choice but to accept his defeat.

I watched The Duellists relatively recently, and I wish I’d gotten to it sooner. I don’t think it quite meets the titanic standards of Scott’s twin pillars of Alien and Blade Runner… but it’s pretty close. The substance he’s sometimes accused of lacking is plentiful here, and when he doesn’t interrogate his characters, it’s an asset. In that way it reminded me of his 2013 film The Counselor, which was similarly happy to follow doomed people inside an absurd system, like bugs in a jar.

The Last Duel arrives forty four years after Scott’s debut, and looks just as austere as you’d expect. He’s had his triumphs over the years, and a good deal of failures, and while I don’t yet know how his latest stacks up, I guarantee it’s going to look incredible.