Revisiting two of Studio Ghibli’s great – and most overlooked – films

The beloved Japanese production company Studio Ghibli has created many famous classics. Critic Luke Buckmaster revisits two of Ghibli’s lesser known efforts – Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Pom Poko – and finds them highly relevant to the present era.

The concept of a dystopian world feels achingly plausible at the present moment. The vague scent of its terrible possibilities has transformed from a Mad Maxian idea, the stuff of apocalyptic fiction, into something infusing the very air we breathe, during this horrific summer of climate change-exacerbated Australian bushfires. The fact that the Bunnings Warehouse closest to my apartment, according to one of my neighbours, ran out of gas masks last week is a sign of the immediate moment, and a taste of what may be to come: a future “new normal” where such masks might be as commonly used as hats or umbrellas.

But how far off into the future? Stan’s futuristic drama The Commons suggests acid rain will fall from the sky in 10-20 years, along with the dawning of a range of other new “normals.”

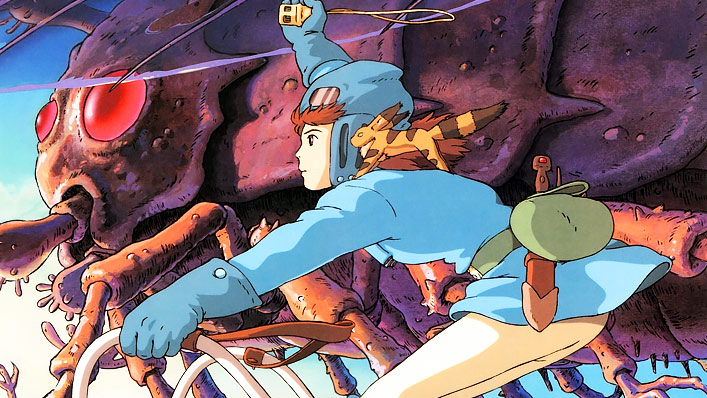

Hayao Miyazaki’s 1984 film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind proposes a more generous timeline – it is based 1000 years after the collapse of industrialised civilisation – but also a much more horrific vision. Civilisation as we know it has gone the way of the Dodo, the planet stained by a terrible “toxic jungle” from which massive, slug-like insect creatures germinate, slithering their awful selves across a ravaged apocalyptic landscape.

It is one of two great Studio Ghibli films that feel, to me, somewhat neglected nowadays, bereft of the cultural cachet they deserve. I arrived at this conclusion after revisiting all the highly influential production company’s films on its ‘The Great Collection’ DVD box set – worth every penny of the $60 I shelled out for it on eBay.

Perhaps their neglected, or semi-neglected status is simply a matter of being overshadowed by other classic Ghibli pictures, which stand and shine like giant totems on the cultural horizon – big names such as My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle.

Nausicaä is an apocalyptic western

Nausicaä actually arrived a year before the formation of the studio, though Ghibli retrospectively claimed the film as one of its own and it is widely considered part of the canon. It was poorly received in countries outside Japan largely because, as this article from critic Bryant Frazer notes, the film was edited down by about half an hour without the director’s approval, removing subplots and even entire characters.

Nausicaä opens dramatically and weirdly: a western by way of an anime by way of a proto-Roland Emmerich disaster movie. A man in a gas mask arrives in a far-flung village covered with ice, the wind a-howling and beastly things the size of small dragons flapping around in the sky above. He enters a hut and picks up a rag doll that crumbles to dust in his hands, before delivering the first line of dialogue, which sets a rather grim tone: “Yet another village is dead.” The man’s gas mask is no cheap number from Bunnings, but rather a heavy duty respirator – the kind wheezed into by Bane or Darth Vader.

Based on a manga book written by Miyazaki, Nausicaä is a film about fighting valiantly, in difficult wars and in terrible circumstances, while maintaining moral integrity and a deep connection with the natural world. Even – and in this case especially – when Mother Nature conjures hideous mutations and extreme weather conditions, as if vomiting up all the terrible stuff humans have pumped into its bowels.

The titular protagonist is the sort of princess you only get in the movies: the kind that never gives up nor loses the common touch. That touch involves horse whispering-like abilities to communicate with the Ohm, the aforementioned slug-like creatures.

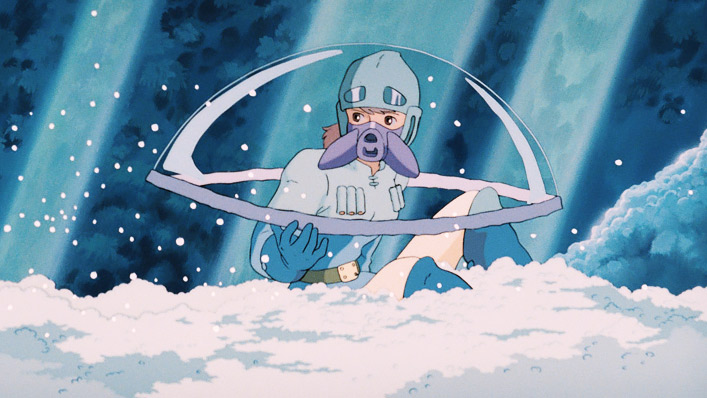

Miyazaki contrasts extreme beauty with extreme danger, the sight of wonder inseparable from a gloomy underpinning reality. In one bittersweet sequence the princess gets covered with a snowflake-like substance that showers out of a huge creature’s pores; she notes that these gorgeous powder-like elements would kill her if she wasn’t wearing a mask.

Like several of the great auteur’s films (i.e. Kiki’s Delivery Service, Howl’s Moving Castle and Castle in the Sky) when it takes to the skies it soars. There are beautiful horizons in the background and kooky flying machines in the foreground: visions of natural wonder versus cartoon contraptions.

The zany Pom Poko is once seen, never forgotten

The other Studio Ghibli production I want to draw your attention to is less well-known than Nausicaä. It seems – at least in terms of its influence in the western world – to have left virtually no cultural footprint at all. I wonder how it is viewed and remembered in Japan.

That film is Pom Poko, which arrived in 1994 and was directed by Isao Takahata, one of Miyazaki’s long-time collaborators. My oh my, where to start with this cheerfully busy and ridiculously interesting film? It is political and mystical and weird and fussy and colourful; it is Animal Farm crossed with Japanese folklore and ‘direct action’ environmentalism, reflected in the glaze of a pachinko machine.

The narrative revolves around warring tribes of racoon-like creatures called tanuki. They stop fighting each other to come together for a more important challenge: to try to prevent the complete destruction of their natural environment, by the hand of urban developers.

These days the tanuki’s pledge to take direct action against environmentally reckless governments and corporations can be reinterpreted as a call for unity for the people of this world – ours, that is, which is in a spot of bother at the moment – to fight governments and their deep-pocketed pals, such as those in the fossil fuel industry.

It’s difficult to separate these two films from the present moment

The tanuki are unified in purpose, more or less, though factions and infighting causes constant distractions. As does the changing nature of their external reality, influenced by how humans and various vested interests respond. Pom Poko explores the politics of the creatures’ plight in fastidious detail. Its themes revolve around two intertwined things: war and politics. There’s lots of infighting and personality clashes; lots of winning and losing support; lots of planning and doing the numbers.

Oh yes: and these racoon-like characters also love energy drinks and can transform into humans. Because why not?

Pom Poko is packed full of zany subplots and diversions, though there is nuance in the way it explores the ethics of direct action; the questions one must ask themselves when stepping outside the parameters of the law to perform deliberately drastic actions. Overarching societal and environmental catastrophe has a way, or should have a way, as the point is made here, of breaking people out of the safe routines of their ordinary lives to fight for a just cause.

In that sense, with the air and the planet being the way it is today, it is difficult to separate Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Pom Poko – two fascinating and very memorable films – from the current moment. They are worth watching for many reasons. The terrible but compelling correlation between their core messages and the present reality is one of them.