See What You Made Me Do is vital viewing, examining the epidemic of male violence

SBS’s documentary series See What You Made Me Do examines the tragic epidemic of male violence that results in an average of one woman a week being killed by a current or former partner. Cat Woods explores the series and sits down with its host and writer, investigative journalist Jess Hill.

Domestic abuse has typically been a topic for news. In bite-size news reports, the entirety of a woman’s life has been narrowed down to the bleak, reportable facts of her violent death. SBS’s newly launched documentary series See What You Made Me Do seeks to shift the focus onto the lived experience of victims and survivors of abuse. It also proposes solutions that will ultimately provide safety for women and children, while ensuring perpetrators face meaningful consequences.

See also:

* All new movies & shows on SBS on Demand

* All new streaming movies & series

Jess Hill, author of the award-winning book See What You Made Me Do, has extensive experience as an investigative journalist. Her ability to ask difficult questions while providing empathy and astute observance enables crucial discussions around a way forward without getting muddled in political arguments and, vitally, without feeling like the series exploits women’s suffering for media gain.

Over three episodes, airing weekly from Wednesday May 5, Hill travels around Australia to speak to surviving victims who recount the abusive behaviour they endured, and to the families of murdered victims. Hill also talks to abusers and the experts working with them to address behavioural change.

Abuse comes in many forms

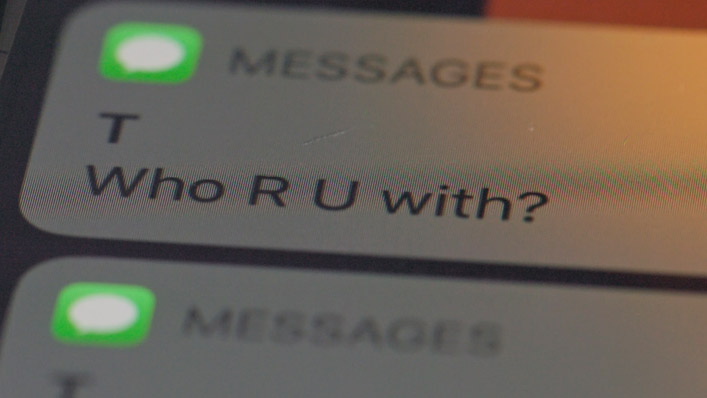

What is very clear from the first episode is that abuse is not purely physical assaults. Male perpetrators manipulate their victims, often through the use of technology, exerting coercive control over their partner or former partner. From tracking women via social media and their phones, to tracing their location with spyware and surveying them in their home and workplace, the toll on victims is—as Hill says—“outrageous.” With only three episodes, Hill admits that the topic can’t be fully and comprehensively covered, but that the stories will likely surprise and compel many viewers.

“The facts can be misleading,” she says. “Data doesn’t tell us everything. The most shocking situations are that the family law system too often forces children to see or live with people they’ve just escaped from and are openly terrified of. That’s what is most shocking and under-reported.”

Australian police attend a call to domestic abuse every two minutes in this country. In one refuge, 85% of the women were being tracked through their phones or through their cars. Hill meets Deb in the first episode, whose husband has planted cameras in every room of the house to watch her. When she meets Hill, she is planning her escape with her kids. Trying to strategise her escape while under surveillance is—understandably—exhausting and frightening.

“When you’re doing something for television like this, you’re just telling a small part of somebody’s story, like what happened in the relationship or what happened just after they left, whereas the full stories are like Hollywood epics or spy novels.”

How to identify coercive control

Over the last seven years, Hill has been contacted by hundreds of survivors who want to tell their stories, so her challenge was to decide which stories would tell the most important details for the public to understand, but equally, to provide potential solutions. It begins, says Hill, with understanding what coercive control is being able to take preventative measures rather than step in at the point where it’s a crisis.

“It’s vital for the victim’s family members and friends to be able to identify coercive control, because it’s often so gradual and subtle that you don’t understand it’s happening. The best protection is for women to know, or for their friends and family to know, so that they can see it for what it is and try to remain in the picture and in touch, to be there for them when they need it. Coercive control isn’t a crime yet, but the Queensland government has committed to criminalising [it], so I guess that will happen in the next couple of years. We will talk about how it’s been criminalised in Scotland in episode three and I hope that it will further inform debate in this nation.”

The use of technology is one of the most incendiary revelations in the series. “Sometimes it can be mundane, like dozens and dozens of text messages daily, or demanding that a partner send a photo every few hours to prove they are where they say they are,” Hill says.

“One woman I spoke to had to take a photo if she walked into another room of the house to prove she hadn’t left. Stalking apps are marketed as apps to let people keep an eye on their kids or employers on their employees. They can turn a phone into a listening device. They’re perfectly legal, they’re invisible on the phone and those GPS trackers can be as low as $9 and installed in the car. That car may be used to escape without the woman knowing there’s a GPS tracker… This is why we’re seeing former cops and private security getting involved.”

There are positive aspects to technology

But technology isn’t all bad. For women who feel isolated or abandoned, access to phones and technology can provide emergency help and access to social media communities.

“It’s essential for a woman’s independence for them to have a phone,” Hill says, adding: “There’s some amazing new technology. You can get a watch that, if you tap it twice, it directly connects to a call centre and it notifies the police if a code word is said.”

Hill refers to the model that is showing promise in Bourke, in New South Wales. “Justice reinvestment is a model of community ownership of this issue, so putting all the different sectors and agencies in close collaboration and getting clear data on what’s happening in particular communities, then treating it as something to be prevented rather than dealing with it once it reaches crisis point. Early intervention and a whole-of-community response—and agency collaboration—that’s the type of accountability that is needed.”

The series can’t come at a more urgent time, either. A man kills his partner or former partner every week in Australia.

“At the moment, perpetrators have the feeling that if they’re a bit careful, they’ll get away with it,” says Hill. “The answer isn’t to look just to the victim.”