Seen That? Watch This: The best cranky Jeff Bridges performances to watch after The Old Man

Seen That? Watch This is a new weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release—here, The Old Man—and matching it to other works, creating the ultimate cinephile homework assignment.

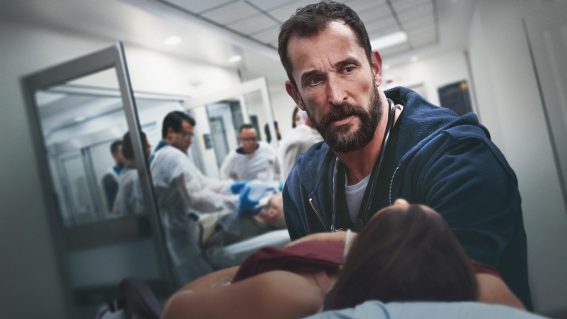

The Old Man begins as it damn well should, sonny Jim—with Jeff Bridges getting up three times in one night to take a pee. On the third visit Bridges’ Dan Chase, a former CIA operative of weak bladder and bedraggled countenance, experiences a vision of a creepy woman in a bathroom (“I sseeee yooouuu”, she hisses). But this seven-part series, developed by Jonathan E Steinberg and Robert Levine, isn’t a horror show. Rather it’s a meditative thriller about the pain of getting out of bed—and evading the occasional assassin.

When Chase speaks to his daughter and hangs out with his dog, he’s a sweetheart; other times he’s a cold-blooded killer. His quiet life in Connecticut is shot to pieces when a (soon disposed of) hitman arrives at his door, triggering an on-the-run narrative. The man “chasing” him—quotations used to indicate neither he nor Chase move very fast—is another ageing bloke: FBI Assistant Director Harold Harper (John Lithgow). In the first episode Harper tells Chase he has two options: go through door number one, which involves him fighting back and “will end badly”, or the preferred door number two—which involves him properly disappearing and severing all ties with his daughter.

The cranky but still dexterous and dangerous old-timer makes it clear he does not appreciate door-related metaphors. “Any more you send to me, I send them back in bags,” he grumbles. “Anyone you send to my kid, I’m sending back in pieces.” Bridges delivers his dialogue in a now-familiar style, speaking as if his lungs have been filled with gravel and a sock stuffed in his mouth. The show’s plot is nothing special but it’s executed stylishly, with moody ambience and low-key lighting.

It ain’t the first time Bridges has played a grumpy old bastard; in fact, the star seems considerably older than 72. When the series finishes—or as fans wait for new episodes, which arrive weekly—audiences may want an extra hit of cranky Jeff Bridges. These three films can help.

Hell or High Water (2016)

Hell or High Water

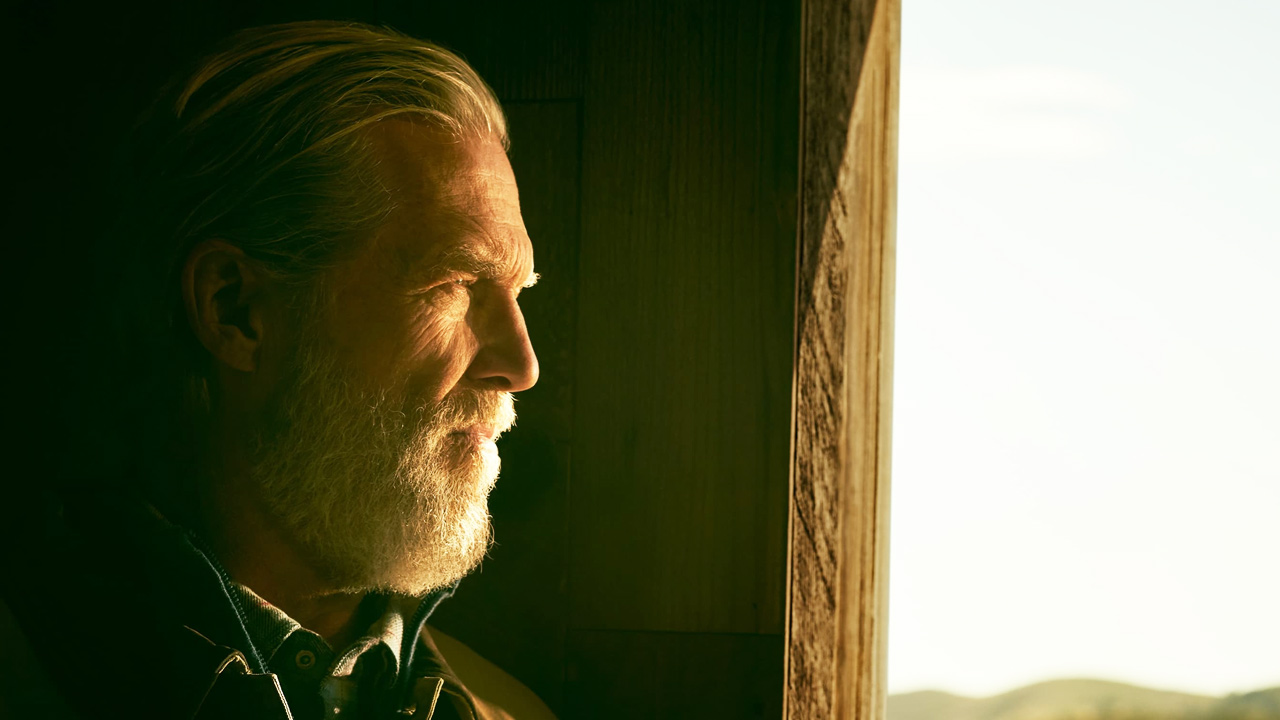

The first shot of Bridges in Hell or High Water shows him sitting at a desk reading a letter titled “Mandatory Retirement Notice.” This injects director David Mackenzie’s film about two bank robbers (Chris Pine and Ben Foster) with the old “last case before retirement” trope. Naturally, Bridges’ Texas Ranger, Marcus Hamilton, is none too happy about this, and also none-too-happy about virtually everything. He even has the temerity to accuse a fellow Texas Ranger, Alberto (Gil Birmingham), of copying his fashion style; his colleague reminds him they wear a mandated uniform.

Although the crux of the drama focuses on the robbers—which the pair pursue at their own, ambling pace—the sweetly bickering relationship between them is one of the film’s pleasures. Hamilton’s “ain’t rushin’ for nobody” attitude reflects the quieter pace of life down south, where people don’t show much respect for the law, or the banks, or gluten-free food options. Mackenzie cleverly frames the bank robbing narrative within the socio-political context of post-GFC America: a systemically and ideologically broken landscape festering with disillusionment, soon to be exploited by Donald Trump. Bridges, of course, was disillusioned way before it was cool.

True Grit (2010)

True Grit (2010)

Marcus Hamilton would appreciate the quote—from Proverbs—that opens the Coen brothers’ adaptation of Charles Portis’ 1968 novel of the same name: “The wicked flee when none persueth.” Like in Hell or High Water, Bridges plays the creaky-limbed man who persueth, rather than, as in The Old Man, the man who runeth or walketh awayeth. He is U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn, who is enlisted by 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) to apprehend the man who killed her father. Bitter and disheveled, because Bridges, and more than happy to send nogoodniks to the great beyond, because western, the star again does his slurring, sock-in-mouth thang—now with added floppy hat and eye patch.

When the pair first interact Cogburn is on the can, Mattie noting from outside that “you’ve been at it for quite some time” (he retorts: “there is no clock on my business!”). Told classily by the Coens, in an accessible but dignified style, True Grit belongs to a pantheon of road movies pairing a youngster with a much older cranky companion, whose softer side is eventually coaxed out of them. The weary Cogburn regularly disappoints the bright and plucky Mattie, inverting the traditional parent/child dynamic. At one point he describes himself as “a foolish old man who’s been drawn into a wild goose chase.”

Crazy Heart (2009)

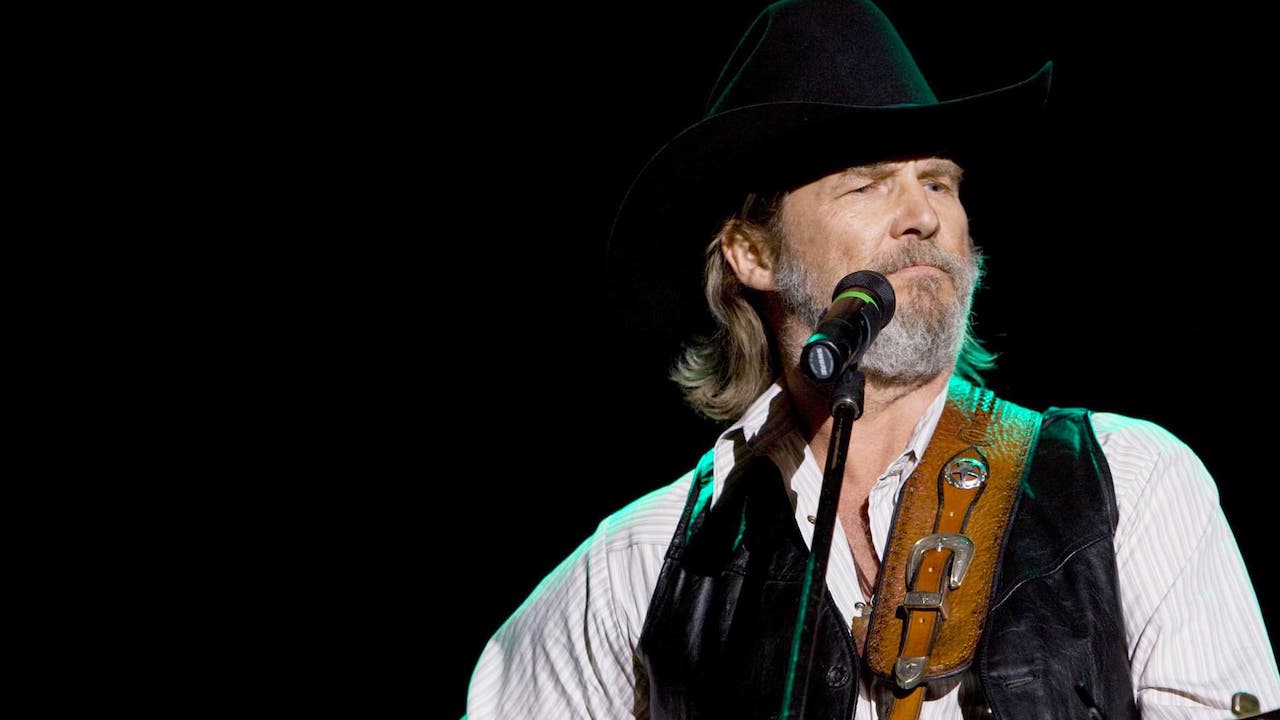

By now we have ascertained that the words “Jeff Bridges” and “over the hill” go together like a horse and cart, or a cowboy and a hat, or a bottle of moonshine at a hoedown. His characters age but the schtick never gets old. In Scott Cooper’s entertaining portrait of a fading country music legend, Bridges really is the movie, totally nailing the pathetic booze-addled Otis “Bad” Blake, who is nearly, but not quite, culturally irrelevant: an almost-has-been. The first time we see him on stage, he’s performing in a bowling alley, singing about how, “I used to be somebody, but now I’m somebody else.”

Proving the truism that no decent person has ever been named Otis, the protagonist ends the gig in true rock-n-roll style: going to a laneway and vomiting in a bucket, then returning to the stage covered in sweat and slime. Crazy Heart includes the familiar “negative prognosis” scene, whereby a doctor informs “Bad” that booze and ciggies don’t belong in the food pyramid, and implores him to change his ways. A new romance with a good-natured journalist (Maggie Gyllenhaal) gives the man with the crazy heart extra reason to clean up his act, but can he keep it all together? Cooper implies optimism but wisely avoids sentimentality.