The Slums of the Future: the suburban static of 40-year-old horror Poltergeist

Celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, Poltergeist is just one of an eclectic selection of films and genres explored in new book We Are the Mutants: The Battle for Hollywood from Rosemary’s Baby to Lethal Weapon. In this exclusive extract, Richard McKenna explores what Tobe Hooper’s paranormal horror has to say about the ’burbs, peering through the static on screen to reveal a pronounced lack of spirit.

Poltergeist (1982)

Online magazine wearethemutants.com is a great destination for reading about Cold War-era popular and outsider culture, with a strong emphasis on speculative (sci-fi, fantasy, horror), genre, pulp, cult, occult, subculture, and anti-establishment media. Excitingly, it’s now manifested in physical form with new book We Are the Mutants: The Battle for Hollywood from Rosemary’s Baby to Lethal Weapon, published today (order a copy here or request at your local bookstore).

The book’s preface describes it as “a critical reassessment of what is arguably the most discussed and beloved stretch of movies in American history. Documenting the tumultuous and transformative years between the arrival of US combat troops in Vietnam and the end of President Ronald Reagan’s second term, we’ve chosen mostly to avoid the restrictive (and, if we’re being honest, overanalyzed) “auteur cinema” canon, focusing instead on an eclectic selection of films and filmmakers across multiple genres—horror, documentary, cinéma vérité, disaster, vigilante action, neo-noir, post- apocalyptic sci-fi—that together capture the push and pull of old and new Hollywood, New Deal and no deal America.”

With each chapter pairing seemingly unrelated films (The Exorcist and Manson; Alien and Sorcerer; Death Wish and Escape from New York, for example), We Are the Mutants finds they “ultimately intersect in meaningful and unexpected ways, both artistically and in the larger arenas of politics and culture”.

In a chapter titled The Slums of the Future, Richard McKenna examines 1982’s Poltergeist alongside 1983 Penelope Spheeris punk drama Suburbia (1983). In this exclusive extract from the book, McKenna explores what Tobe Hooper’s paranormal horror has to say about the ‘burbs, peering through the static on screen to reveal a pronounced lack of spirit.

What’s peculiar about 1982’s Poltergeist is that the thing advertised in its title never appears. The film presents plenty of noise and disruption, yes, but not much sign of anything resembling the unsettling but invisible “noisy spirits” that had increasingly roamed the supernatural-saturated media of the previous decade. This prudish reluctance to engage with the confusing and frightening “realities” of the supernatural captures something about the film—a literal and figurative lack of spirit at its heart that inevitably evokes its setting.

How do you speak about the suburbs without descending into cliché, given that an all-consuming, all-enveloping cliché is precisely what the suburbs were designed to be? One of the most pervasive tropes of postwar American life and popular culture, the ‘burbs taught the entire world an immediately recognizable iconography for sedate middle-class comfort: the wide streets flanked by large detached houses with double garages and immaculate lawns kept moist by the persistent hissing of sprinklers (persistent and catastrophic droughts be damned), children riding bikes and Big Wheels, joggers and dog-walkers, station wagons gliding back and forth, no shops, no litter, no crowds, no unpleasant surprises that can’t be averted by prudent planning.

The word “suburb” has its origins in suburbium, Latin for a peripheral part of a city, but the North American version, made possible, or necessary, by the real animating spirit of twentieth-century American culture—the automobile and 41,000 miles of a new Interstate Highway System—had developed into a new kind of autonomous settlement: one that explicitly rejected the city’s confusing accretion of humanity and unmediated spaces that purportedly made the country a melting pot of races, ethnicities, and beliefs. In short, middle-class whites built walls around themselves, and took their tax dollars with them. Black and non-white families, pointedly kept out of the suburbs for decades by “restrictive covenants” and a federal refusal to insure mortgages, inherited the suddenly disinvested cities, some of which stood in for future dystopias in films like Escape from New York.

The fact that Poltergeist was helmed by Tobe Hooper, whose gift for skewering a certain kind of curdled Americana had been evident since The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, suggested that Poltergeist would subvert the stereotypes and expose the inchoate fears lurking beneath the green belts and sunspangled swimming pools. If so, it wouldn’t be the first time: the suburbs had been trite shorthand for the various existential malaises plaguing the middle-class psyche in any given moment for decades, from 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause to the 1964 Twilight Zone episode The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street, 1968’s The Swimmer, 1975’s The Stepford Wives, 1978’s Halloween, and 1979’s Over the Edge, which took inspiration for its story of kids rebelling against the boredom of their planned community from real events in Foster City, California.

Famously, Poltergeist opens with the sound of “The Star-Spangled Banner” playing over a black screen, upon which the film’s title appears in stark white outline text—the implication being that the noisy spirit of the title might actually be America itself. It’s one of the film’s few genuinely inspired moments. The camera slowly pulls back from a close-up of a TV screen as the images of the US Marine Corps War Memorial signal the day’s close of broadcasting—when there still was a close of broadcasting—and give way to static. We glide past the body of Steve Freeling (Craig T. Nelson), slumped inert in an armchair, and take a tour of the bedrooms where the rest of the Freeling family are asleep: spunky housewife Diane (JoBeth Williams) and the three Freeling children, teenager Dana (Dominique Dunne), pre-teen Robbie (Oliver Robins), and little Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke).

The Freelings live in Cuesta Verde, a vast, anonymous, and seemingly entirely white suburb somewhere in California, built by the same real estate development company where Steve is a hotshot salesman. When one potential client protests that he can’t tell one house from another, Steve doesn’t argue but simply points out that “our construction standards are very liberal”: the chance to indulge yourself with an outdoor jacuzzi or swimming pool, it’s implied, is a worthwhile trade-off for the production-line uniformity and lack of character.

The origins of Poltergeist‘s story nominally lie in the 1958 events that plagued the Herrmann family of Long Island, who claimed they were being tormented in their recently built suburban home by an entity that confounded the efforts of an investigating team of scientists from Duke University’s Parapsychology Laboratory.

In the case of the Freelings, the problems begin when little Carol Anne descends the stairs to the living room in the middle of the night and begins to talk to the “TV people” she claims live inside the static, unnervingly responding to questions that only she can hear. Scored with nursery rhyme music that highlights the reassuring, family-friendly nature of the setting but also provides an unwitting critique of this infantile and reductive version of the world, a montage of scenes of suburban life follow that concludes with Steve and his friends yelling and jeering at a football game on the screen of the same TV we saw in the opening scene.

The boorish show of performative aggression is cut short when the game is interrupted by a children’s show, the soothing Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, triggering an argument between Steve and his next-door neighbor: their TV remotes are tuned to the same frequency. Encouraging seclusion and intensifying the suburbanites’ reluctance to share spaces, TV clearly sits at the heart of this unmoored existence, and the spat concludes with a mock gunfight—American men of a certain age always a hair’s breadth away from acting out the deathless archetype of the cowboy—to decide which of the images flying about like bullets will dominate the screens.

Meanwhile, Diane is stopped from flushing the corpse of the family’s pet canary down the toilet by Carol Anne—it’s left to the youngest Freeling, who has not yet been indoctrinated with the pain-free pragmatism of the suburban adult mindset, to insist on the need for ritual and a little respect for the dead. Before long, though, Tweety’s grave will be desecrated by the bulldozer digging the swimming pool that, naturally, the upwardly mobile Freelings want to add to their home.

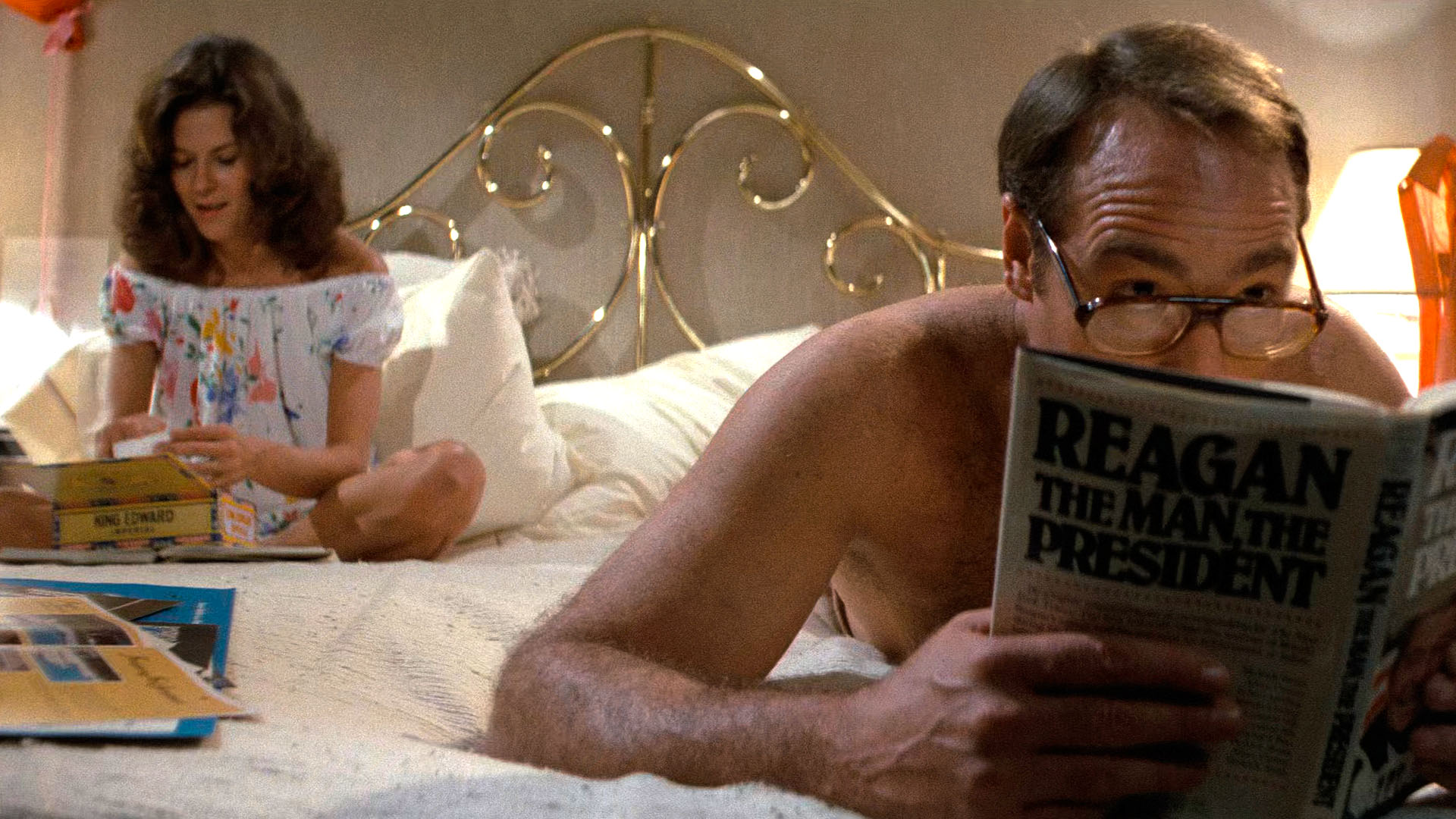

Despite their boomer lifestyle pretensions, Diane and Steve spend their evenings smoking pot in bed like a couple of college kids. She reads about Jung and he reads about Ronald Reagan, opposing ideologues with a common gift for engaging with their respective followers’ dreams. But the domestic idyll is shattered when Diane discovers a strange force manifesting in the kitchen that stacks the chairs and slides family members across the floor like a theme park ride.

Initially, she’s enthusiastic about the novelty, but after Robbie has been attacked by the tree outside his bedroom window and Carol Anne is sucked into the walk-in closet, her voice calling out from the TV set, she and Steve turn to the “Popular Beliefs, Superstitions and Para Psychology” department of the local university to investigate. The team of researchers, including the maternal Dr. Martha Lesh (Beatrice Straight) and Dr. Ryan Mitchell (Richard Lawson), are shocked at the supernatural chaos that now reigns in Carol Anne’s bedroom: a hurricane of special effects work that functions as a metaphor for the film as a whole—a meaningless storm of costly nonsense in a space devoid of any human presence.

Unaware of the paranormal events and worried that Steve’s absence from work might mean he’s thinking of changing companies, his boss Teague (James Karen) takes him for a stroll up in the nearby hills, offering him the chance of a “phase 5” home near the graveyard overlooking the already outdated original Cuesta Verde development. (In his 1964 book God’s Own Junkyard, architecture critic Peter Blake compared the suburbs to automobile graveyards and military cemeteries.) “We’ve already made arrangements for relocating the cemetery,” explains Teague when Steve expresses unease, adding, “It’s not ancient tribal burial grounds […] it’s just… people.” He pauses. “Besides… we’ve done it before.”

It’s one of the film’s more egregious sleights of hand, not only sidestepping the issue of whose cultural sites actually had been desecrated historically to make way for the American built environment, but also appropriating that frisson of feeling wronged and transplanting it onto the white population—which is admittedly less offensive than the original version of the screenplay, then called Night Time, where the source of the supernatural disturbances is a vast grave site resulting from a massacre of white settlers by Native Americans.

The baffled researchers call for backup in the shape of a medium called Tangina (Zelda Rubinstein). Unlike the conformist Freelings and the straight-laced researchers, Tangina, with her Southern accent, diminutive stature, rock’n’roll charisma, and unambiguous belief in a reality that transcends the kinds of materialism valued by suburbanites and academia, looks and acts like an outsider. Although in many ways as hackneyed as everything else in Poltergeist, she’s also by far the most engaging character in the film, her working-class cred unwittingly highlighted by the well-spoken Dr. Lesh when she tells a skeptical Steve that Tangina has “cleaned many houses.”

Tangina explains that Carol Anne has been abducted by something called “the Beast,” and a rescue effort ensues that involves sending Diane into the other dimension inside the closet, then pulling her and Carol Anne back out into the suburbs. (A little girl who disappears into another dimension inside her own house, unseen but clearly heard by her frantic parents, is the plot of 1962 Twilight Zone episode Little Girl Lost, whose writer Richard Matheson says Spielberg asked him for a video copy while developing Poltergeist.) In contrast to the haunted room scene earlier, the sequence dispenses with flashy effects and makes do with strobes, spotlights, and a smoke machine—a de-escalation of production values that results in some of the film’s most memorable imagery.

Once an ectoplasm-smeared Diane and Carol Anne have reemerged, Tangina announces that the “house is clean,” and, like the entrenched-in-denial boomers they are, Diane and Steve promptly go back to acting almost as if nothing has happened, the irruption of the irrational that only hours before threatened the lives of their children resolved by a psychic “cleaner” as decisively as an infestation of roaches might be resolved by an exterminator. After they decide to stay in the house one last night while preparing to move out, Steve absents himself to the office, naturally, and the children are sent back to their bedroom, which only hours before was the locus of hell. Diane, meanwhile, indulges in a long bath.

This nonchalant parenting approach might almost be a deliberate poke at boomer child-rearing if it weren’t so clearly of a tonal piece with the mindset of the rest of the film: whether it’s sending traumatized kids off alone in taxis, smirking indulgently as lecherous workmen catcall their teenage daughter, or, again, thoughtlessly putting their children to bed in the same room where they have narrowly escaped being killed by an evil ghost called the Beast, they aren’t callous, just completely, devastatingly oblivious to the potential effects of their decisions on their kids’ lives. At the same time, they themselves are profoundly infantile, as when they’re goofing around in the bedroom like a couple of teens, or when Steve duels with his neighbor over control of the TV, or in the scene where Diane sits on Dr. Lesh’s knee and puts her arms around her neck like a child seeking comfort.

Inevitably, as the parents are off attending to their own needs, the supernatural forces reappear to claim their kids. While Diane is drying her hair, oblivious to the fact that Robbie is being choked by a possessed toy clown, she is attacked by demonic forces that yank up her top to reveal her panties before throwing her around the room (even though the scene only lasts a moment, it’s a disconcerting tonal switch from childishness to something even more unpleasant). Diane rescues the kids from another attempt at dimensional-closet-sucking, and Steve returns home to find corpse-filled coffins blasting up through the ground. When Teague appears, Steve suddenly realizes what’s going on: “You moved the cemetery but you left the bodies, didn’t you? You son of a bitch, you left the bodies and you only moved the headstones!”

The film ends with the neighborhood hemorrhaging market value as water mains burst, gouts of flame erupt from the sidewalks, and the Freeling house is sucked into oblivion in a scene that echoes the finale of 1976’s Carrie: homes that have witnessed an injustice annihilated by supernatural forces; malignancies lopped off the perfect suburban body. Their home taken from them by forces beyond their control, the Freelings check into a motel, foreshadowing a reality that growing numbers of middle- and working-class families would experience over the decades to come as they paid the price for cheap mortgages and a lack of financial regulation. Steve’s one concession to the gravity of the events that nearly cost him his wife and children is to put the room’s TV set out onto the balcony—though we sense it probably won’t be out there for long.

An attempt to reconcile two profoundly disparate visions of America—with writer-producer Steven Spielberg’s bratty, cloying embrace prevailing over Tobe Hooper’s tense worrying at the scabrous underpinnings of the nation’s life and culture—Poltergeist is, then, a pretty accurate avatar of its setting: phony, unprincipled, and not what it claims to be. With its wearying atmosphere of Halloween phoniness, Poltergeist turns something that should be frightening into something by turns wheedling and hectoring: a detached postmodern freak show that wants you to both love it and fear it, and whose desire to be all things to all people means it ends up being nothing more than a safe, fundamentally reassuring ride through the greed and ruthlessness the film pretends to critique with its “ghosts as victims of capitalism” schtick.