Stateless should restart a discussion about how Australia treats asylum seekers

ABC’s detention centre-themed Australian series Stateless is a hugely gripping drama. George Newhouse from Macquarie University wonders whether it will restart the discussion about how Australia treats asylum seekers.

Most of Cornelia Rau’s family and friends have regarded the screening of Stateless with trepidation because the television series is loosely based on her troubled life.

In 2004-05, Cornelia Rau was wrongfully detained for 10 months at a Brisbane’s women’s prison and later Baxter immigration centre after authorities assumed she was an illegal immigrant. Yvonne Strahovski plays flight attendant Sophie Werner, who is based on Rau, in Stateless.

The Rau family’s primary concern is to mitigate any adverse impact it might have on Cornelia’s well-being, but there has been undeniable curiosity in the community about how Cate Blanchett and her team would handle one of the darkest episodes of our nation’s modern history.

Human stories

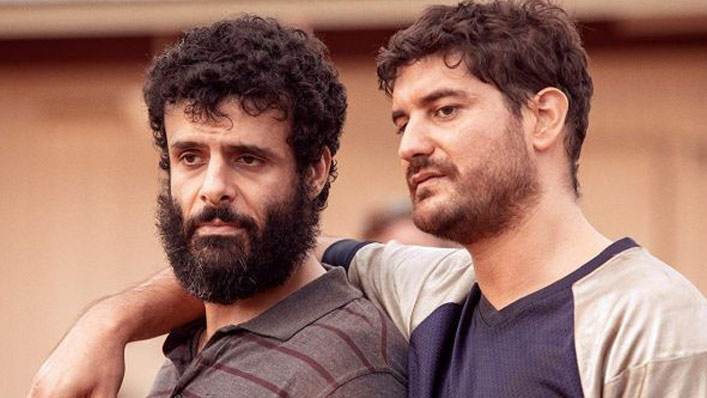

Stateless packs a lot into six episodes. It follows the lives of four characters: a detention centre guard and a bureaucrat who are engaged in running a remote immigration detention centre, and an Afghan refugee and the Rau character, Sophie, who are their prisoners.

Careful character development helps us to understand the complexities of each of their lives. Everyone at the detention centre is running away from something or someone. Sophie is running from a manipulative cult; the Afghan refugee is escaping from the violence of his homeland. We also learn that the guards and the Department of Immigration staff are running away from something, too.

While that theme is used to humanise the individuals, at times it trivialises the prison experience. However, the real power of the series is the way it uses people “just like us” as a Trojan Horse to expose the racism, sexism, misogyny, dysfunction and violence of a privatised prison system implementing a policy of institutional cruelty.

Sophie’s suffering provides us with a window into a dystopian world inhabited by “outcasts”, like asylum seekers, that our government goes to great lengths to stop us from seeing. Mental illness is a taboo that is difficult to air publicly, but Stateless deals sensitively with the exploitation of Sophie by a rapacious cult leader who broke her soul. The series also exposes the callousness of officials who did not care.

Midway through the series the message that everyone is compromised and that no one is unblemished becomes clear. Everyone appears to be lying at some level, even if it is only to themselves. The lies are compounded by the state-sanctioned violence and spin that damages and corrupts everyone that comes within its orbit.

As we watch the systemic dehumanisation of individuals in the camp and the corrosive impact on those in charge of them, one begins to understand how the German people could became Hitler’s willing executioners.

But Stateless doesn’t harangue, its power comes from drawing together the common humanity of those who are damaged by a brutal policy of violence and indefinite detention.

Remember when we cared

The series made me nostalgic for a time when Australians were united in their horror at what our government had done to Cornelia Rau.

After Mick Palmer published his report on Rau’s experience, the Howard government took immediate steps to improve transparency and institute independent medical oversight of the detainees. But 12 years after Rau’s torture was revealed, Tony Abbott reversed those protections and Australia’s immigration detention system quickly spiralled into another crisis.

In my work with the National Justice Project (NJP) – a not for profit legal service – I know of cases of adults with mental health problems lost in the detention system for a decade. I saw children who had been detained on Nauru for five years, witnessing untold horrors including assaults, lip-sewing and self-harm and, as a result, attempted suicide. My legal team had to take the Minister for Home affairs to court to force him to provide sick children with desperately needed mental health treatment.

I have dealt with every Immigration Minister since Philip Ruddock and I have never seen things so dire. Having fought for better health care in detention for well over a decade, I am fed up with politicians destroying the lives of men, women and children as a deterrence to others.

Now we know … and don’t care

Watching Stateless makes me realise how much worse things are today than in 2005, because today the damage is being done knowingly.

Under Peter Dutton’s term as minister we have seen a militarisation of the Department of Immigration through the establishment of the Border Force. Under his watch, increasingly tougher Border Force policies and practices have been used as a weapon to deter boat arrivals. Conditions for the men, women and children transferred to offshore detention have deteriorated to the point that a prosecutor of the International Criminal Court described the duration, the extent and the conditions of detention as a crime against humanity.

Stateless is one of the best Australian dramas I have seen in a long time. I hope it will restart the discussion about who we are as a nation and whether we are comfortable with the crimes against humanity being done in our name.

Stateless airs on the ABC on Sunday nights until 5 April. It will then screen globally on Netflix.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Harry Freedman who worked tirelessly for Cornelia Rau and Vivian Solon.![]()

George Newhouse, Adjunct Professor of Law, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.