The 20 most significant motion pictures of the decade

Reflecting on the tumultuous 2010s, critic Luke Buckmaster proposes a different kind of ‘best of the decade’ list – and picks the top 20 most significant motion pictures of the last ten years.

The acclaimed theatre production Mr Burns, A Post-Electric Play is set in a dystopian off-the-grid future where a travelling troupe of actors recreate an episode of The Simpsons. They don’t just recreate what they remember of the show, but also what they remember of advertisements and popular songs broadcast on television – which are performed in vibrant musical numbers.

The point is that on a long enough timeline, all artistic creations become artifacts of the historical period in which they were created. The art the Post-Electric troupe remember and celebrate did not cease when the commercial breaks began.

This line of thinking, emphasising the message over the medium, has arguably never been more important than today, in this strange and interesting age of disruption and media convergence. Old distinctions are becoming increasingly passé (the word “film,” for example, historically describes reels of plastic and gelatin emulsion) while “motion pictures” are everywhere, permeating virtually all forms of modern media.

With this in mind, I decided to take a broader look at the most significant motion pictures of the 2010s. The choices on this list encompass a range of manifestations – including feature films, television, commercials, apps, video games, and virtual and augmented reality – leaning heavily on the cultural relevance and/or impact of these productions. The list includes stand-alone titles, entire series and everything in between; in one instance a particular moment during a live TV broadcast.

The word “significant” has been carefully chosen: it’s not necessarily indicative of quality, like “best,” and is less authoritative than “important,” with more wiggle room to make connections. Did I miss some? Of course I did. Please tweet at me and share your additions.

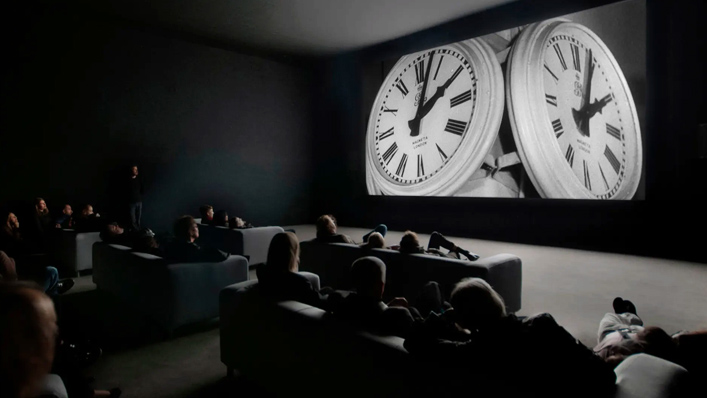

The Clock

In the era of remix culture and IP appropriation, one colossal beast of a film towers above them all. Christian Marclay’s The Clock premiered in 2010 and became the world’s most popular piece of concept art, entirely comprised of short snippets from hundreds of films. It runs for an arse-flattening 24 hours, what you see on screen always matching the time in real-life. Marclay’s extraordinary, narrative-less experience proves form always trumps content and signifies a different kind of meta storytelling, using assemblage to recreate meaning: what the two-artist collective Soda_Jerk describe as “a form of rogue historiography.”

The ‘I’m on a horse’ Old Spice ad

Who could forget Isaiah Mustafa taking a shower, standing on a boat then sitting on a horse? Director Tom Kuntz’s single shot commercial, which sparked one of the most successful marketing campaigns (‘The Man You’re Man Could Smell Like‘) in internet history, combines minimal frame movement with innovative use of space, aligning human physicality (what abs, Mustafa!) with real-world inventions tailored for the screen in very clever ways – like in a Buster Keaton film. Check behind the scenes videos such as this for a taste of how this (and subsequent) Old Spice ads were made.

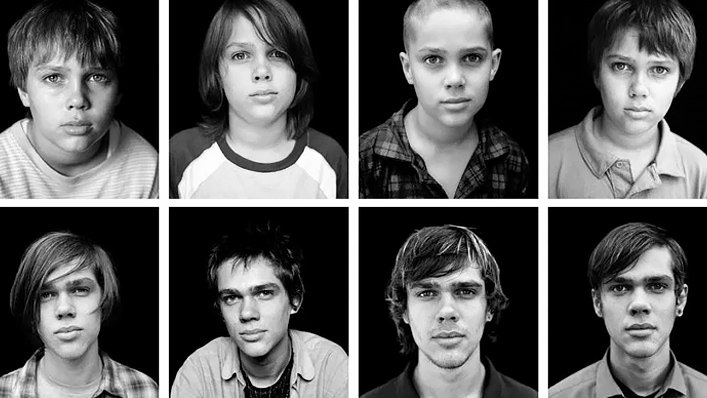

Boyhood

James Stewart once described film as “moments sculpted in time.” Director Richard Linklater’s heartwarming 2014 drama, which was shot over 12 years and follows Mason (Ellar Coltrane) from early childhood to college, feels more like a life sculpted in film. The director took the curse of ageing and turned it into a special effect, making a point that our lives are driven by narratives and narratives revolve around our lives – the tales we tell essential to making sense of the world. In the words of Jean Luc Godard: “Sometimes reality is too complex. Stories give it form.”

The La Land Land / Moonlight Oscars debacle

When La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz held up the Best Picture envelope at the 2017 Academy Awards, declaring Moonlight the real winner and his presence on stage a mistake, the ceremony’s producers brilliantly if unintentionally reflected feelings that had been festering in many of us for while. To wit: that we are living in times of great uncertainty and even unreality, where things that could not possibly happen are happening, including and especially the global climate and ecological crisis hanging over everything. Also that we could no longer trust any institution, from circlejerk awards ceremonies to the highest offices of the land.

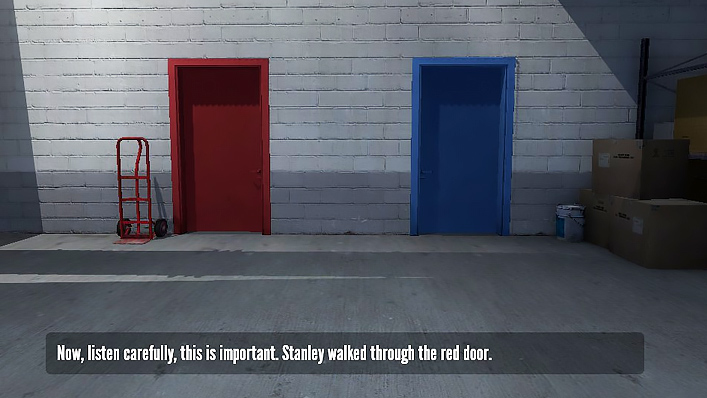

The Stanley Parable

In this experimental video game, released in 2013, players inhabit the body and first-person perspective of the titular office worker, whose colleagues have all mysteriously disappeared. A narrator extensively comments on everything he/we does or is about to do, including which entrance he/we will chose to walk through.

The twist is that the player gets to decide what to do after hearing the narrator. Do we obey this omnipotent being or prove him wrong? Game writers/designers Davey Wreden and William Pugh pose big questions about the nature of choice and predestination in interactive storytelling; where its liberties and limitations lie. Once experienced, never forgotten.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe

The extent of Donald Trump’s impact on politics can be measured only through the scale of its destruction. The pumpkin-coloured idiot obliterated any semblance of civility, dignity or integrity: the monster of backroom America finally laid bare. Similarly, in Hollywood, the dominance of the MCU throughout the 2010s marked the era in which the studios stopped pretending: that they were making art; that they were even making films.

The scariest thing was not that the bean counters had finally, resoundingly trounched the artistes, but how readily audiences ate it up and how few people mourned what was lost. Also how the vast majority of critics – afraid of being relegated to the outskirts of cultural oblivion – gave a new era of noxious nonsense their blessing. I wrote this essay in April, exploring the MCU-dominated state of multiplex cinema.

Doctor Who: Twice Upon a Time

Since its inception, the men in control of motion pictures have blocked women from key creative positions and protected the patriarchy. That did not change when Jodie Whittaker became the first female actor to play Doctor Who, after 12 men before her – an obscene scenario given the famous character is a Time Lord who can inhabit any kind of body in either gender. And yet, when Whittaker first appeared as Who in this 2017 Christmas special (she would properly inhabit the role in subsequent episodes) the moment was undeniably symbolic of a new and exciting era for women.

![]()

Avatar

James Cameron’s blockbuster – for a while the most successful film in box office history, until Avengers: Endgame beat it – opened in December 2009, but drew most of its success in the early moments of the new decade. Avatar makes this list not because it left a cultural footprint, but because it didn’t. Its insignificance is its significance. We all saw it then we all kind of forgot about it.

This was despite Cameron’s insistence on including issues of substance, which would prove highly relevant in coming years: i.e. protection of the natural world from destructive capitalism, and the need to embrace indigenous communities in times of ecological crisis. Avatar gave us a vision of how to achieve a better world, and we looked the other way. Audiences don’t remember the lessons learned on Pandora, but they do remember dancing Baby Groot.

Job Simulator and Alumette

2016 marked a major turning point for virtual reality: the first time VR headsets became commercially available on the mass market. Among this important period’s triumphs is the zany Job Simulator, which is set in a futuristic world where robots resembling Macintosh computers recreate situations from the bygone human era, resulting in a clever and funny satire about worker drone human life. The ability to pick up objects and physically walk through virtual space is connected to a satisfying narrative counter to the “once upon a time” paradigm that has been so prevalent for so long.

On the other hand, the dazzling Alumette suggests “once upon a time” might be alive and well in the era of VR. Director Eugene Chung remakes Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Match Girl, setting it in a futuristic city in the clouds. The viewer assumes the presence of a god, with the power to observe a poignant drama about a mother’s sacrifice for her young daughter but no ability to alter its outcome. Alumette is still a perfect gateway experience for newcomers to VR; they will get a whiff of the potential of this new and extremely exciting artistic medium.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

“Self-plagiarism is style,” said Alfred Hitchcock. Few directors are therefore as stylish – according to Hitch’s dictum – as the wonderfully self-plagiarising Wes Anderson, whose seductive visual identity has had a huge impact on popular culture. Anderson’s style was refined before the start of the decade but really took hold in the age of Instagram.

Some have even suggested that the rise of symmetrical colour-saturated food photos on social media is a result of Anderson aesthetic. I chose 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel for this list not because it is necessarily the most influential of his films, but because I think it is his best, and the greatest example of that highly distinctive style.

Pokémon Go

The “motion” was real – as in, real people in transit, literally moving the (also moving) pictures in their hands. Fusing the realities of an invented narrative world with the actual, physical one, using location and map-based technology, Pokémon Go delivered blockbuster AR in the form of a high-tech scavenger hunt. It highlighted the sort of ethical issues that can arise when multiple tiers of reality unite in a single physical space, which invariably has its own realities and histories. Pokemon characters came to Auschwitz and Hiroshima, for example, and numerous people were killed while the game was being played.

Breaking Bad

I’m showing my prejudices here, because I couldn’t bare to include a list of motion picture highlights from the 2010s and not include one of my all-time favourite TV shows, which premiered in 2008 but ran until 2013 (and is still running, if you count Better Call Saul and the recent El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie.

Vince Gilligan’s knuckle-gobbling series about a cancer-riddled teacher-cum-drug-lord (Bryan Cranston) and his student-cum-righthand-man (Aaron Paul) expresses the ongoing relevance of the writer’s room: an approach in many respects antithetical to the auteur theory. The dual questions (as Gilligan has stated) driving this brilliant drama are simple but crucial, and will never lose currency: 1) where’s a character’s head at? and 2) what happens next?

The Babadook

How do you continue to innovate, in an old school medium – in this instance feature films – strongly associated with a perception that we’ve seen it all before? One option, as the director Jennifer Kent demonstrated in her 2014 horror movie par excellence, is to take us to a place we cannot visit through any means other than images; somewhere in our dreams and nightmares. The Babadook, dook, DOOK’s many champions include The Exorcist director William Friedkin, who – not inaccurately – described it as one of the scariest films ever made.

Get Out

Also in the horror genre, director Jordan Peele deconstructed racism in Get Out, skewering the myth of a post-racial America by casting his villains as Obama-voting white liberals. It was a decade in which the power of horror as political commentary provided fascinating vantage points from which to view various social issues, from fear of ‘The Other’ (Us) to sexually transmitted diseases (It Follows). Some called it a golden age.

Grand Theft Auto V

GTA 5 (released in 2013) earned more than $6 billion in sales, becoming the best-selling entertainment product in history. With great success derived from great, provocative art (it is probably the most gripping video game I have ever played) comes great controversy. Players for instance were able to lure and murder sex workers. Does that make the game creators misogynistic, the players misogynistic, or both, or neither? To what extent should open-world experiences apply ethical limitations, and how should one determine what those limitations are? GTA 5 continued a debate also sparked in previous installments.

Top of the Lake

For a long time television has carried with it the stigma of a “lesser” medium than cinema. In the 2010s that pointless way of thinking (‘small screen bad, big screen good’) finally went out the window. Jane Campion was among the great, veteran directors who took their “cinematic” visions to the teev, with her masterfully made mystery-drama Top of the Lake – which she created, wrote and co-directed.

Face App

You could argue a process that simply changes one still image into another – creating a vision of what it thinks a person will look like in the future – is a push when it comes to fitting the definition of a “motion picture.” On the other hand you could argue that one image sequencing into another is the very bedrock of motion pictures. Meaning inferred in the space between two juxtaposed images is created by what’s sometimes called “the mind’s eye.” In the example of Face App, the mind’s eye is, in a sense, life itself: the ageing body escorting you from the first picture to the second.

Game of Thrones

The most popular TV show of the decade brought smut to the mainstream, big time. There has always been violent and controversial art – but not on this scale, with this size of audience, turned into such a global stadium spectacle. Incest, beheadings, blood and tits: I don’t need to remind you why Game of Thrones’ was risqué. That is not to say it was meaningless; for me the show is about the difference between pursuing destiny and suffering fate.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

This restlessly inventive visual cocktail from co-directors Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey and Rodney Rothman perfectly suited the mood of the times. Not because it presents a universe of countless realities – each harbouring a different version of the titular superhero – but because each reality brought a distinct aesthetic.

That is a mind-boggling view of subjective experience, the very shape and form of the world varying from eye to eye. Joining a trend of films I dubbed multidimensional modernism, Into the Spider-Verse considers art – and even the universe – as an infinite cycle of creations within creations. Not an origins film, but a film about the myth of origins.

The Ice Bucket Challenge

A seminal moment in social video filmmaking. The power of a single idea trumped everything – narrative, production values, etcetera – creating a work of uncontrollable elusiveness. Everybody saw it but nobody saw it; it stayed the same but it was different every time.

Your friends, your family, the guy down the street co-starred alongside the world’s most famous actors, democratising performance and transforming it, at the behest of the creators, into a form of embodied philanthropy. The Ice Bucket Challenge’s stunt-based concept harks back to the earliest days of the moving image: what the academic Tom Gunning famously called “the cinema of attractions.”