The exhilarating spectacle of Beyoncé’s Homecoming

Beyoncé’s Netflix documentary Homecoming is destined to be the concert movie of the year, if not the decade. Luke Buckmaster explores this dazzling experience and its cinematic precedents.

What a spectacle! Beyoncé’s new Netflix documentary Homecoming, which captures the superstar’s watershed concert at last year’s Coachella music festival in California, was described by The New Yorker as “an education in black expression.” After watching the film – an all-singing, all-dancing, all jiggling and jiving celebration of music, feminism, black culture, performance power – and reading that New Yorker piece, one naturally wonders what other texts could be on the curriculum, and what other homework assignments (more, more!) might be required to study at this booty-shaking school of ostentation.

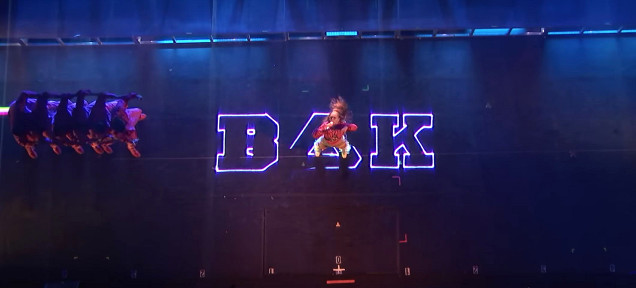

Homecoming is a concert extravaganza with enough lashings of lights to awaken a nation of somnambulant cave dwellers, and enough machine-generated smoke to clog the lungs of every bedazzled attendee. Or so it seems. The event marked the first time the festival has been headlined by a black woman since its inception in 1999. It is long overdue, to say the least, and Beyoncé relishes the spotlight with commensurate verve.

Actually, let me rephrase: she doesn’t so much relish the spotlight as transform it into a blazing ball of awesomeness. Sparks literally and symbolically fly. The famously multi-hyphenate artist is clearly the god of this universe, commencing her show descending from the top of a pyramid of industrial metal bleachers to command her dynasty and its many slack-jawed, starstruck disciples. This hyper-choreographed pageant comes across in essence as both ancient and contemporary. Especially when Beyoncé, at just past the twenty minute mark, starts stomping on the ground, as if performing a fierce tribal warrior dance, before crying out for the audience to “ssssuucccckkk on my baaaallllsss!”

It’s a lot more than just spectacle. Threaded throughout the show are bite-sized narratives immaculately performed by Beyoncé and her dancers (sometimes self-contained but usually threaded together in service of a larger picture) and imagery connecting to black history in America, such as the culture of historically black colleges and universities. Writing on this subject for Salon, Aisha Harris described ‘Beychella’, as fans and the media have dubbed it, as “rich with subtext, littered with as many Easter eggs as Ready Player One.”

Co-directed by Beyoncé and Ed Burke, the key challenge faced by Homecoming – and the source of its greatest limitations – comes down to its dual purposes: as a live event for festival attendees and a spectacle for the cameras. ‘Beychella’ was live streamed to an online audience of 458,000 viewers. The Netflix documentary is a third iteration of the experience, combining concert footage shot on two weekends.

During an early performance of Crazy in Love, Beyoncé is surrounded by women in yellow costumes and yellow berets, and men also in yellow but with black berets. At one point the camera snakes down behind the star, then POW! – the film cuts to a front-on view of this colourful collective. But everybody is now dressed in pink rather than yellow: an impossible wardrobe change. These switches are present throughout, in moments such as this:

To achieve this the directors deployed one of the oldest and fundamental film editing techniques – called ‘cutting for continuity’. This is used to create cohesive sequences that remove a chunk of time between two visual points. The classic example is of a person ascending the stairs: we see them at the bottom of said stairs then – cut! – they are at the top. Usually that unnecessary bit in the middle consumes a small amount of time – let’s say, a minute or so of stair climbing.

But in Homecoming a week separates these moments, which are joined to create one continuous instant. It is a neat trick, which initially has the visual impact of a grand David Copperfield-like stage illusion; we blink our eyes and ask how did they do that? It becomes clear that the filmmakers are pogo-ing between timelines, flipping between two versions of reality. Throughout the experience the cameras are drawn back to the stage as if by magnetic force. It is, after all, a breathtakingly co-ordinated and vocally flawless performance, almost surpassing the inevitable limitations of capturing a stage event – where the camera’s ability to roam is fundamentally limited.

As the world revels in Homecoming, it’s worth exploring how filmed stage musical productions have evolved, especially those where the camera has been liberated from a live audience – that is, when the film audience are the ones being primarily performed to.

There are lots of examples strewn throughout movie history. Here’s a famous scene from 1943’s Stormy Weather, which was described by The Oprah Magazine as “one of the best showcases of 40’s Black excellence.”

I love how there are three tiers of reality: the audience and the band; Lena Horne up on the stage; and the world outside her window. Through this window we see small details that would not have been visible to the live audience inside the film’s world. This information is conveyed for the camera.

One of the rare examples in Homecoming of a moment specifically captured for the camera and not the live audience – where the camera dances, as well as the performers – occurs in the below shot, which arrives almost an hour in.

After watching this the work of Busby Berkeley leapt to my mind like spitting embers coming out of Beyoncé’s canons. The legendary Hollywood musical choreographer is famous for, among other things, highly distinctive overhead images, which he captured from hydraulic platforms (this was well before the days of drone photography). His work is still dizzyingly beautiful and hypnotic today.

There are few scenes in musical history as magical, and as exquisitely cinematic, as the Shadow Waltz sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, which was released during the titular year. If you don’t believe me here are 105 seconds that might change your mind:

As you can see: the camera dances, not just the performers. Berkeley’s signature shots turn groups of dancers into beautiful moving floral patterns, some almost Escher-like in their symmetry. A scene near the end of another of his films, Footlight Parade (also from 1933) has an incredible interior set full of waterfalls and women in bathing suits.

Berkeley’s arrangements are utterly spectacular. One potential downside is that these compositions dehumanize the dancers by turning them into abstractions, the emotional details conveyed by their faces and body language lost.

Beyoncé and Burke are more human-oriented in Homecoming. It is a quintessentially human story, after all, focusing on both individual and collective expression. This focus feeds into a broader point made in the famous quote by Audre Lord, which is displayed on screen late in the film: “Without community, there is no liberation.”