The one great thing about the Insidious movies

Since premiering in 2011, the Insidious franchise has burrowed its way into horror cinema. The films can be a bit bumpy, but they share one excellent feature: a nightmarish world called the Further. Luke Buckmaster explains what makes it great.

Insidious: The Red Door

I appreciated one thing about Insidious: The Red Door before I’d even seen it: the idea of an entire film built around a visual motif. A tonne of horror iconography is spread throughout the Insidious franchise, from good ol’ fashioned creaking floorboards to rocking chairs that move by themselves. But a bolder and less genre-rified recurring image is that of a door, painted in bright fire engine red, dramatically contrasting the dense darkness around it. It’s always dark, in this land of the red door, because it’s located in the Further: a nightmarish purgatory or world between worlds where all sorts of hideous nasty pasties roam around.

Returning to the Further is, for me, the opposite of what it’s like for the characters: they’d prefer to be anywhere else and I love coming back. This space is what gives these (sometimes quite rote) films novelty factor and atmospheric zhuzh. Part of the Further’s appeal is that, rather introducing entirely different settings, it’s a kind of double or simulacra of the physical world that shares spatial properties, repurposed into a kind of hellish half-reality.

When Josh (Patrick Wilson) enters it in the first film, to retrieve his astral-projecting son Dalton (Ty Simpkins), he arrives not in a dramatically different place but in the same space, his house, albeit in a different and far less pleasant spot on the astral plane. The fourth (and worst) film in the series—Insidious: The Last Key—moves away from the idea of the Further as a double of the world, introducing unseen spaces in an attempt to expand lore and legend.

Thankfully, The Red Door reverses that trajectory and returns with a bang to the Further as a duplicate. It also brings back Josh, his now ex-wife Renai (Rose Byrne) and their children Dalton (Ty Simpkins) and Foster (Andrew Astor), who weren’t in the third and fourth outings. Set 10 years after the second film, Josh and Dalton have had their memories of the Further suppressed. But hideous apparitions start invading their waking life, and Dalton—now enrolled at university—realises he has the ability to astral project. That means we get two versions of campus locations: the “real” ones and the Further-ed ones.

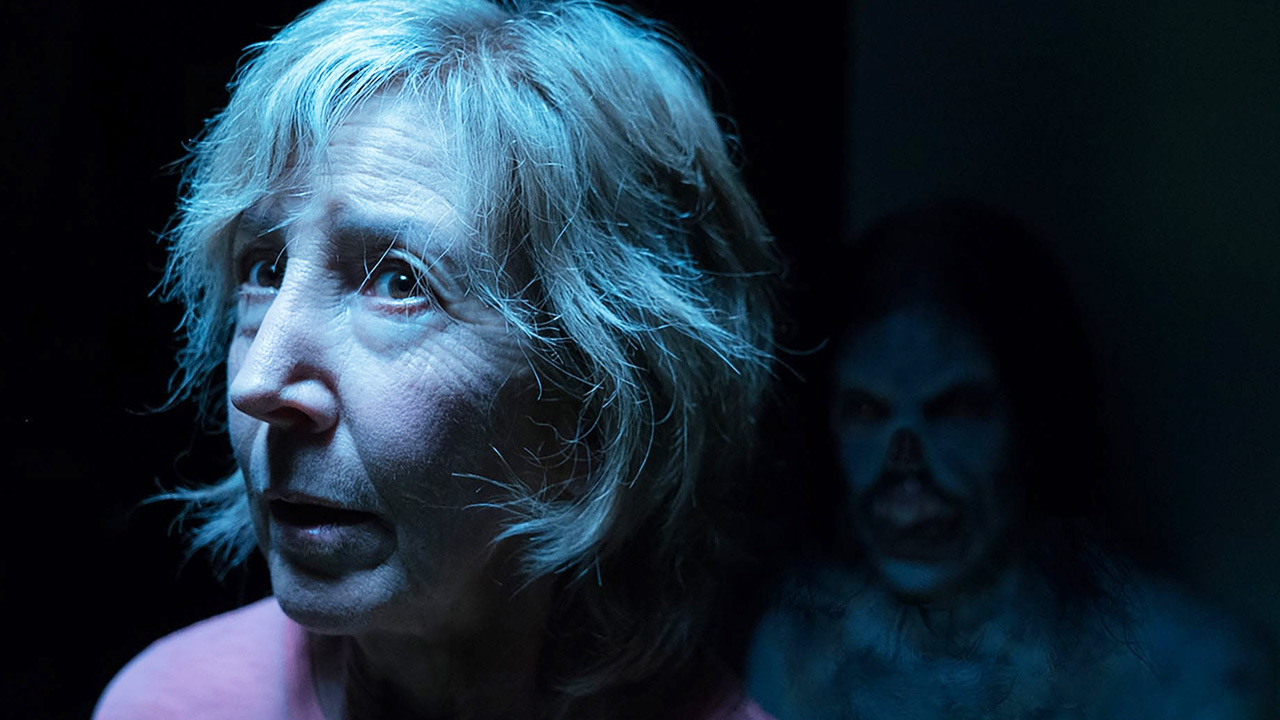

We’re never told that the Further is the work of the devil, or that the Insidious universe has a heaven and hell. Demonologist Elise Rainier (Lin Shaye) uses the terms “light and dark.” Whenever you have a tough day at work, by the way, think about poor old Elise, facing down ghouls in the spirit realm and literally dying on the job. Despite being killed in the first film (a move director James Wan and writer Leigh Whannell might regret, given the narrative sleight-of-hand necessary to keep bringing her back) she’s been in every sequel. Albeit with little more than a cameo in the latest one.

From a production perspective, the Further’s recalibration of pre-existing spaces is a clever way to keep costs down. The same sets are presented with starkly different—far dimmer—colour schemes dominated by cold midnight blues. Sometimes we watch characters enter the Further purely through palette changes. The Last Key and The Red Door each contain an elegant, unbroken shot visually expressing an arrival. A close-up of a person’s face (Caitlin Gerard’s Imogen in The Last Key, and Dalton in The Red Door) changes from full colour (the real world) to thick gluggy blue (the Further).

Switching realities allows for various atmospheric flourishes. In Insidious: Chapter 3, for instance, when Elise enters the Further and walks down a hallway, the film deploys the surreal vision of it raining inside.

The overlapping of spaces also allows for interesting interplay between the real world and its Halloweenish mirror. You never know how or when the two will connect. Take a climactic scene in Chapter 2 when Josh—situated outside of his house in the Further—knocks on the front door. Nothing happens in the real world: so close, yet so far away. But when Josh hears his baby scream from across the astral plane, he busts through the door in the Further, which forces ajar both versions of the door. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of logic here, but you don’t think about that in the heat of the moment, when all sorts of crazy crap starts flying around.

I was pleased to see The Red Door returning to the idea of the Further as a bizarro mirror universe. Combining real and other world spaces is a particularly compelling concept in a contemporary society increasingly overlaid by virtual and augmented realities. The emerging mediums of VR and AR shift away from sectioned off areas of representation, such as television and cinema screens, towards experiences that encroach on physical spaces, sometimes also (like in the Insidious movies) offering unexpected interplay.

Countless films embrace the idea of computers producing immoral or amoral things, from robots like HAL to the embodied software of Agent Smith. But what if danger came from a volumetric copy of the entire world (which isn’t the realm of fiction) with an ability to negatively influence, or even haunt, our own world? What if we struggled to know the difference between them?

Perhaps this mind-blowing concept is why I’m so fond of the Further. Josh, Dalton and the rest of the gang don’t enjoy creeping through mist-filled hallways filled with demonic monsters—but I’ll keep coming back for more.