The ‘gamble’ of Wonder Woman paid off. Now what?

Last year’s Wonder Woman tore up the rulebook – or at least Hollywood’s collective “wisdom” – when it comes to superhero films. Not long after Patty Jenkins’ film raced to over $821 million worldwide came the emergence of the #MeToo movement, seemingly unconnected but both speaking to the grim reality of gender bias in the world of commercial filmmaking. Katie Parker considers the film’s success through the lens of the events that followed, and looks towards the future.

For female audiences, enduring an endless stream of doomed girl power movies is just another part of being a woman. It’s kind of like a tradition: Hollywood, deciding it is time to once again fill a mysterious, unspoken quota, will generously allow a female character or female director (rarely both at the same time) the chance to lead a major big budget blockbuster all of their very own. Promoted in these terms, and met with equal measures of unrealistic hype and screwy, sexist backlash, the film, unable to meet expectations, will be panned: dismissed as yet another little experiment that tried hard but just didn’t work, an ill-advised gamble that would be treated with greater caution next time. A case in point: Lexi Alexander’s excessive, enjoyable, Punisher: War Zone which bombed off a $35 million budget in 2008, relegating her to sporadic TV work.

Perhaps this is why Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman, the first major comic book film of the current era to be helmed by a woman, was greeted with a collective sigh of relief. Opening to not only a warm critical reception but also record-breaking box office, word quickly spread: the film was actually good.

Following Diana, a warrior princess turned superhero who leaves her all-female utopian island paradise to help an American spy end World War One, Wonder Woman is radical in the quietest way. Rather than load it up with a wacky feminist agenda or subtext, Jenkins’ departure from the norm is simple: make a film about a woman through the lens of the female gaze. The result was transformative: imbued with the kind of empathy and warmth that male directors so often equate to weakness and frivolity, Diana’s strength comes not in spite of her femininity but because of it. Couple this with the fact that the film is totally entertaining and utterly charming and you wonder why it hadn’t happened sooner.

Five months later, news of the allegations against Harvey Weinstein broke. The legendary film producer and co-founder of Miramax Films and The Weinstein Company had, it was alleged, spent the great part of his career harassing, abusing and assaulting young actresses. Those who incurred his ire were silenced with settlements and legal threats, bestowed with ‘unstable’ reputations and blacklisted, never to be seen in mainstream movies again.

That Hollywood should be the birthplace of what is known now as the #MeToo movement seems more than just incidental and is telling of a number things: of the industry’s hypermasculine, domineering power; of the significance of representation both behind and in front of the camera; and of just why a cinematic moment like Wonder Woman has taken so long to arrive.

The primary reason Hollywood would have us believe, it seems, is that it was just too risky. In the lead up to its release, the oft-spun narrative around Wonder Woman told of the extraordinary move undertaken by the studio allowing a woman known primarily for her work in TV to helm a major blockbuster worth such a lot of money. In the words of a Hollywood Reporter profile of Jenkins: “Warner Bros. gambles $150 million on its first woman-centered comic book movie with a filmmaker whose only prior big-screen credit was an $8 million indie.” Never mind that the lil’ $8 million indie, was 2003’s acclaimed Monster which took in $60.4 million and won Charlize Theron an Oscar.

The idea that women or people of colour are somehow ‘riskier’ choices to lead major mainstream products is a myth that has long permeated Hollywood, and one that is intrinsically linked with what has been revealed by the #MeToo movement.

What we know now is that for women in Hollywood the obstacles have long been far greater than merely convincing studios to take a chance on them. By pushing women out of the industry, the behaviour of Weinstein and his ilk have systematically, deliberately ensured that films like Wonder Woman – and the female talent necessary to get them off the ground – are nearly impossible to get made. Wonder Woman stands as not only a testament to the specific value of female filmmaking, but as a reminder of the work that has been lost over the years.

The careers of actresses like Annabella Sciorra, Mira Sorvino, and Rose McGowan may not have faltered had they not been blacklisted by Harvey Weinstein; filmmaker Brenda Chapman might not have been removed from directing Brave, the story she created, were it not for Pixar’s John Lasseter’s alleged harassment and misconduct; even Jenkins herself would have beaten her own milestone as the first woman to direct a comic book movie way back in 2011 had she not been unceremoniously dropped as the director of Thor by Marvel in favour of Game of Thrones veteran Alan Taylor.

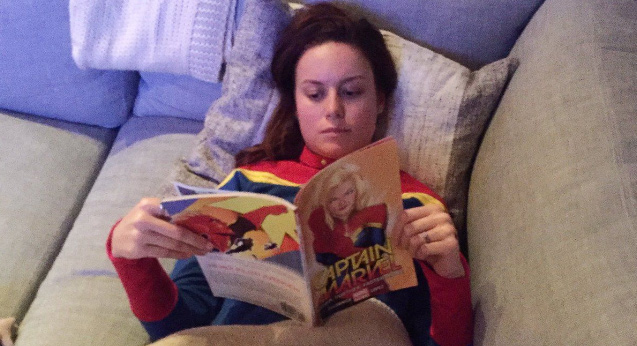

In the wake of the success of projects like Wonder Woman and Black Panther, Hollywood has, of late, sprung into action to jump aboard this progressive new bandwagon. Already the comic book world is working on three new female-led additions, in the form of DC’s New Gods (to be directed by Ava DuVernay), Marvel’s Captain Marvel (starring Brie Larson and co-directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck), and the Wonder Woman sequel which will see Jenkins return.

How long will it last? It remains to be seen. For Hollywood, it has long been convenient to use financial imperatives to explain away the lack of female representation in front of and behind the camera, and in an industry more concerned with protecting predators than amplifying diverse voices, it is no accident that the myth that female-helmed projects are “risky” has survived for so long. Yet with the changes that have taken place over the last year, it does not feel entirely naive to have hope that things are shifting.

Some critics in the current climate have argued that Wonder Woman did not go far enough. The subjugation Diana experiences is never reckoned with; there are nearly no other female characters; there’s a makeover scene; not to mention that few could argue former model Gal Gadot does not meet every unrealistic standard of beauty one could imagine.

Yet it would, I believe, be a mistake to undervalue or underestimate even the most incremental cultural shifts when they are done on such a massive scale. As an entry to the mainstream comic book movie canon, Wonder Woman is a triumph, not only for its entertainment value, but for what it’s global success proves. It’s true that female filmmakers bring a specific – and often alternative – perspective to what they create. What is not true is that audiences, in their droves, aren’t ready to embrace this in the mainstream. Wonder Woman is proof that female filmmakers are not a gamble – and if they are, it’s one that pays off.