The one question that makes Joker: Folie à Deux a fascinating movie

Joker: Folie à Deux is anything but ordinary. Love or loathe it, this is a bold and daring movie, centering one question it constantly asks but doesn’t want to answer, writes Luke Buckmaster.

Virtually everything about Todd Phillips’ Joker sequel is engineered to imply it’s totally bonkers—a case of the inmates running the asylum. First and most obviously, that absurdly hifalutin title—a French term for a psychiatric syndrome, which doesn’t exactly scream “box office juggernaut.” Then there’s its peculiar structure, the film’s second half being mostly a courtroom drama and the entire runtime interspersed with musical sequences, featuring a hoarse-sounding Joaquin Phoenix blurting show tunes. Phillips is careful not to make him sound either good or deliberately bad.

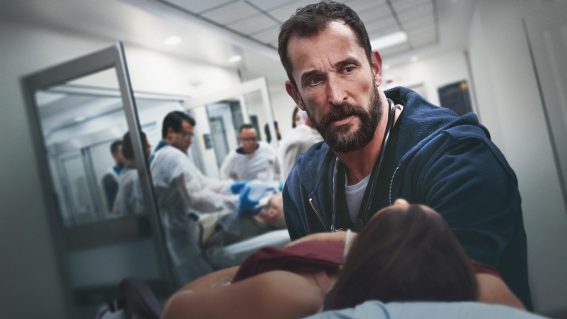

Behind the veneer of batshit crazy spectacle lies a deceptively complex and deep thinking film, obsessed with its own outréness but also intellectually daring and unquestionably original. Joaquin Phoenix returns as Arthur Fleck, aka the titular character, again bone-thin and sporting an odd hunch, cooped up for much of the runtime. First languishing in Arkham Asylum and then fronting judge and jury, on trial for brutally murdering a handful of people (as depicted in Folie à Deux’s spectacularly popular predecessor, Joker). But really it’s the very concept of the Joker that’s on trial.

Fleck’s lawyer, Catherine Keener’s Maryanne Stewart, wants to convince the jury that Fleck is insane, recruiting experts to establish connections between childhood trauma, mental illness and violent tendencies. Her biggest problem is that Fleck may not be complicit in the plan; saving himself is not a key priority. The writers (Phillips and Scott Silver) connect insanity to the very existence of the Joker, making a point that if Fleck insists the latter exists, he admits to the former. This might spare him from the electric chair but will strip away his agency, and his ability to regard his own actions as fundamentally his.

This conundrum is exacerbated when Fleck is seduced by an uber fan, Lady Gaga’s Harleen “Lee” Quinzel—aka Harley Quinn—who loves him less for who he is than what he did, and the world-burning nihilism he stands for, if he stands for anything at all. Even though Phillips constantly raises that central question—is Fleck crazy?—the director doesn’t want to answer it either. An answer in the affirmative—he’s sick—places the Joker in a diagnosable category, dangerously close to suggesting his villainy is not really, or at least not fully, his fault. Going in the other direction—implying he’s sane and rational—minimizes the Joker’s signature loopiness, suggesting it might all just be calculated spectacle.

Watching Folie à Deux constantly avoid the very question it’s constantly engaging with makes it fascinating—and helps explain why it’s a musical. Those musical sequences are essentially a series of daydreams, some frivolous and others violent, which may reflect the characters’ actual feelings and motivations, but also may not. Nobody can be judged for what they do in their dreams.

Making things even more interesting, while also draining the film of colour and life, is the manner with which Phillips downplays the obviously ostentatious qualities of these musical moments. Even when Gaga and Phoenix are literally singing and dancing in the rain, buildings burning behind them, the future pregnant with possibility, the tone is heavy-hearted, almost stolid. It’s not a celebration; the cork stays in the bottle.

If the aforementioned question (is Fleck insane?) is the core of the film, another one had me engaged in deep thought on the train home. Is there a difference between mythologising and demythologising? In other words, is the latter even possible? Both I and, I think, the film, believe the answer is no: you cannot demythologize the Joker, just as you cannot demythologize Marilyn Monroe or Jesus Christ. Any attempt to strip away their legend is just another extension of that legend, another motion in pop culture’s infinite cycle.

Folie à Deux’s ending makes this clear, for spoilerish reasons I mustn’t go into here. Suffice to say that Phillips et al seem to view the Joker as a Guy Fawkes by way of Banksy figure: anyone who wears the mask embodies the legend, and the mystique around the creator or perpetrator has a contagious effect, emboldening imitators. These ideas nudge the film towards the terrain of Joseph Campbell’s myth of origins, arguing there really was no original Joker, just as there is really no original anything. Le monde est une scène.