The Science Behind Movie Time Travel

I’m sure any reasonable person with access to a time machine would use it for pure-of-heart actions, like warning the world of an economic collapse or telling the Rena captain to take a slight left.

Not me though, I’m hopelessly impulsive towards my own pointless agendas.

When I was a kid on February the 19th 1997 at precisely 1:34pm, I made a promise to myself: if I were to ever invent a time machine, I’d travel back to that exact moment and hand my seven-year-old self the deed to the Poppa Jacks factory.

Two things happened:

1) I didn’t get that deed.

2) I realised my future self never invented the time machine.

So, I did what any wannabe temporal venturer did, ate a crap-load of Poppa Jacks, became a film geek and indulged in every time travelling film I could target.

With years of uncredited knowledge under my fez* (along with a quick visit to www.timetravelinstitute.com/theory), let us try to apply the four main theories of time travel to every single 4D-crossing film ever made.

Or the ones I feel like.

*fezzes are cool

Theory A: Fate (Circular Causation)

We’re all aware of the social idea of fate: every moment in everyone’s lives is on a fixed track, with any change being an impossibility. This runs true for our first theory in time travel. The universe is linear, completely immune to change in either the past or the future. Any event caused by a jump from present to past (or future) has already occurred (hence the alternate title “Circular Causation”).

Have a gander at my stupefied diagram of the theory:

So, if a bold traveller were to voyage back in time to prevent Stephenie Meyers from ever being an author, they’re destined to fail, perhaps even winding up being the one who inspired her to write blood-sucking-hickey fiction in the first place.

It’s often a device used to sprinkle on clever plot twists that feel organic to the story (when done right, of course). It’s part of what made Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azkaban so awesome (spoilers, BTW). Nearing the climax of the film, Harry and Hermione travel back to, essentially, save themselves. It all fits in context to what happened during the scenes they revisit. Why they chose to never use the device again throughout the rest of the saga is beyond me.

However, the most complex and most satisfying to witness example of circular causation is Triangle. If you haven’t seen it, check it out. If you have, enjoy my incredibly basic temporal diagram that does not do the movie any justice.

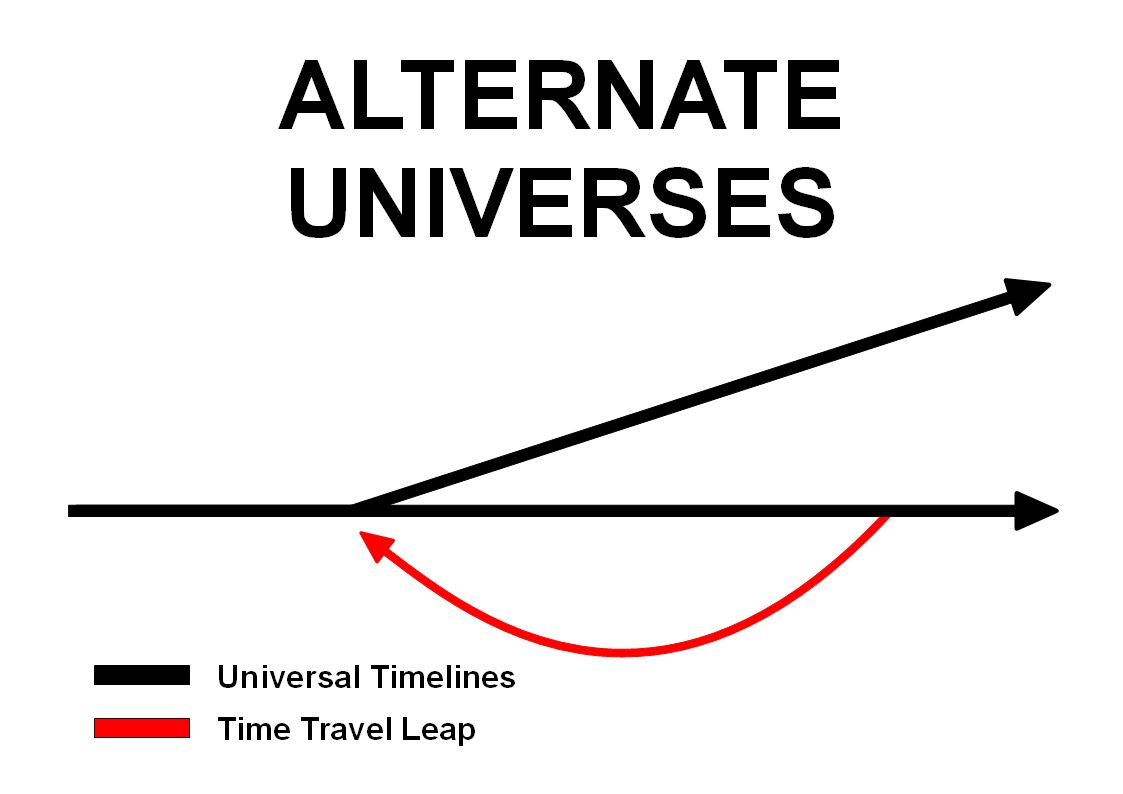

Theory B: Alternate Universes

The second theory I plan to butcher is definitely the most scriptwriter-friendly. It runs off the idea of parallel dimensions, that every alternate action creates an alternate universe. So, I could choose to either continue writing this article or get the sleep I so desperately need. In that split instant, two universes are created: the first, which sees an eyelid-sagging writer hopelessly devoted to his 12 readers completing a blog post which will most likely be riddled with typos, and the second, which sees a very happy Liam awaking gloriously in the morning only to read the headline: 12-member movie cult cause mass suicide.

Was that a little convoluted? Well, here’s another diagram:

A shift in time allows a change to be made. The most prominent example lies in 2009’s Star Trek. In order to preserve the continuity of the TV series (alongside the sensitive respect of Trekkies), J.J. Abrams pulled out his loophole of awesomeness, using time travel as a device to start a whole new universe within a whole new continuity. Pretty sneaky, J.J.

Theory C: Success

This theory is kind of like the unlovable inbred pug baby of Circular Causation and Alternate Universes. Success reverts to the idea that the universe is linear (no alternates here). However, a leap back through time can cause a permanent change to that linear universe, meaning the events that were suppose to happen before the change become non-existent.

What makes this theory so damn unappealing is its allowance for paradoxes (…paradoxi? …paradeuce?). Let’s say I were to go back to when I was a baby in the womb. I grab the umbilical cord and strangle myself to death. This would not have occurred if I didn’t travel back in time in the first place. Of course, now that I’m a dead baby, I cannot grow up to travel back in time to make my suicide possible. Luckily, no movie that I’m aware of uses such a depressingly stupid scenario.

However, just because the theory is the least favoured doesn’t mean it should be shunned in the moviemaking world. Hell, one of the best time travel movies ever made followed Success to success. Back To The Future had Marty McFly on constant alert as he constantly faded in and out of existence depending on how successful he was at hooking his parents up (or not).

The timeline did change though. Marty’s Dad grew a backbone and The Twin Pine Mall was renamed The Lone Pine Mall (seriously, it was, check it out). However, Marty’s birth still occurred. That event remained in the timeline. Here’s my simple-minded attempt at understanding it.

The chances that the altered timeline would still show up with the event that Marty travels back in time is miniscule.

Theory D: Observer Effect

This last theory is much like Success but without the unattractive threat of a paradox. Any change due to time travel can occur. However, the travellers remain unaffected. It’s not really clear why this would be the case, but it’s assumed that it’s due to the travellers being “out of time” or being outliers in the dimension, I suppose. It’s kinda like this:

It’s a popular theory in film and television, partly due to its user-friendliness. However, it’s also a rather fluffy one. The idea of travellers being unaffected simply due to timey-travelly-quantum… stuff… never really seems to stick. It’s also ambiguous as to what effects the travellers undergo when being “beyond time.”

It’s a popular theory in film and television, partly due to its user-friendliness. However, it’s also a rather fluffy one. The idea of travellers being unaffected simply due to timey-travelly-quantum… stuff… never really seems to stick. It’s also ambiguous as to what effects the travellers undergo when being “beyond time.”

Nevertheless, the theory’s the basis of many a great flick, and it allows us to get around them nasty-looking paradoxes.

An example that probably wouldn’t’ve crossed your brain is Groundhog Day. As discovered by a writer more dedicated than I am, Phil Conners (Bill Murray) spends almost 34 years trapped in the reoccurrence. He never ages, however, for each day pays no physical toll on him due to the Observer Effect. Here’s my pathetic attempt at documenting it:

I gave up at 20-something

Not every film feels the need to strictly adhere to one theory, nor should they need to. Hell, what do we know? The universe is only going to expand to a point where all matter freezes. I doubt we’ll find a way to traverse the time-mensions by then, so we’ll never know which theory (if any) is the true victor.

Hot Tub Time Machine uses a combination of Success and Observer Effect to tell its largely tounge-in-cheek-and-other-nasty-places story. Back To The Future 2 takes it up a notch by smashing bits of the prior two with Alternate Universes.

To end, you’ve got the rare flick that gives the incompetent middle finger to quantum mechanics, favouring it’s own scientific rules of temporal bullshit. Such bullshittery can be found in the film The Sound Of Thunder, the adaptation of a book that deserved so much better.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XxhxmGHLQko&NR=1

I’m not going to degrade myself into unpacking its mentally handicapped understanding of time. Let me just say this: it’s like they took all four of my diagrams, placed them on top of each other on an HP projector, put points on every intersection, removed the diagrams and connected the dots to make a fucking unicorn.

I wish I could’ve mentioned all the great time travel movies out there, but time’s a bitch, and we love her so. Still, here’s an honourable mention to the films I wish I could’ve nodded to:

Terminator 2: Judgement Day

Austin Powers 2: The Spy Who Shagged Me

The Time Machine

Bill And Ted’s Excellent Adventure

Timecrimes

Superman

TimeCop

Click