The Tattooist’s Son adds a new, deeply moving chapter to a Holocaust experience

A personal pilgrimage from Melbourne to Auschwitz proves to be a moving journey in The Tattooist’s Son, writes Steve Newall.

As the world commemorates the 80th anniversary of German Nazi concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz’s liberation, one of the many horrific accounts of what took place there gets a new, deeply moving chapter.

Telling an unlikely love story set in a reprehensible place, last year’s The Tattooist of Auschwitz explored some perhaps unexpected dramatic terrain. Based on the bestselling novel by Heather Morris—part memoir, part historical fiction and based on the recollections of Slovakian survivor Lali Sokolov—the miniseries recounted the horrors of Sokolov’s Holocaust experiences as told to the author.

What Sokolov shares with Morris in the dramatised adaptation is a lifelong romance, forged within the concentration camp’s confines, and offering sparks of hope and humanity amid the horror. But as we learn in new documentary The Tattooist’s Son, this was a story that Sokolov never shared in detail with his only child Gary. It was only after the death of Lali’s wife Gita that he felt free to tell his story to Morris—but as Gary tells us regretfully here, people who read the book knew more about his parents than he did.

The moving documentary is a voyage of discovery for Gary, as he travels from his parents’ post-war adopted home of Melbourne to the notorious site of mass extermination in Poland. It’s a journey Gary has been compelled to take, wanting to stand where his parents stood, and understand more about their experiences.

As you can imagine, these are not easy steps to take. “I’ve been avoiding doing it,” Gary tells us at one point: “I didn’t go four times before this trip—I don’t want to make it number five. This time I’m going.” A big motivator is being able to explain more about his parents to his own children, and what Gary discovers in his pilgrimage is both devastating and enriching.

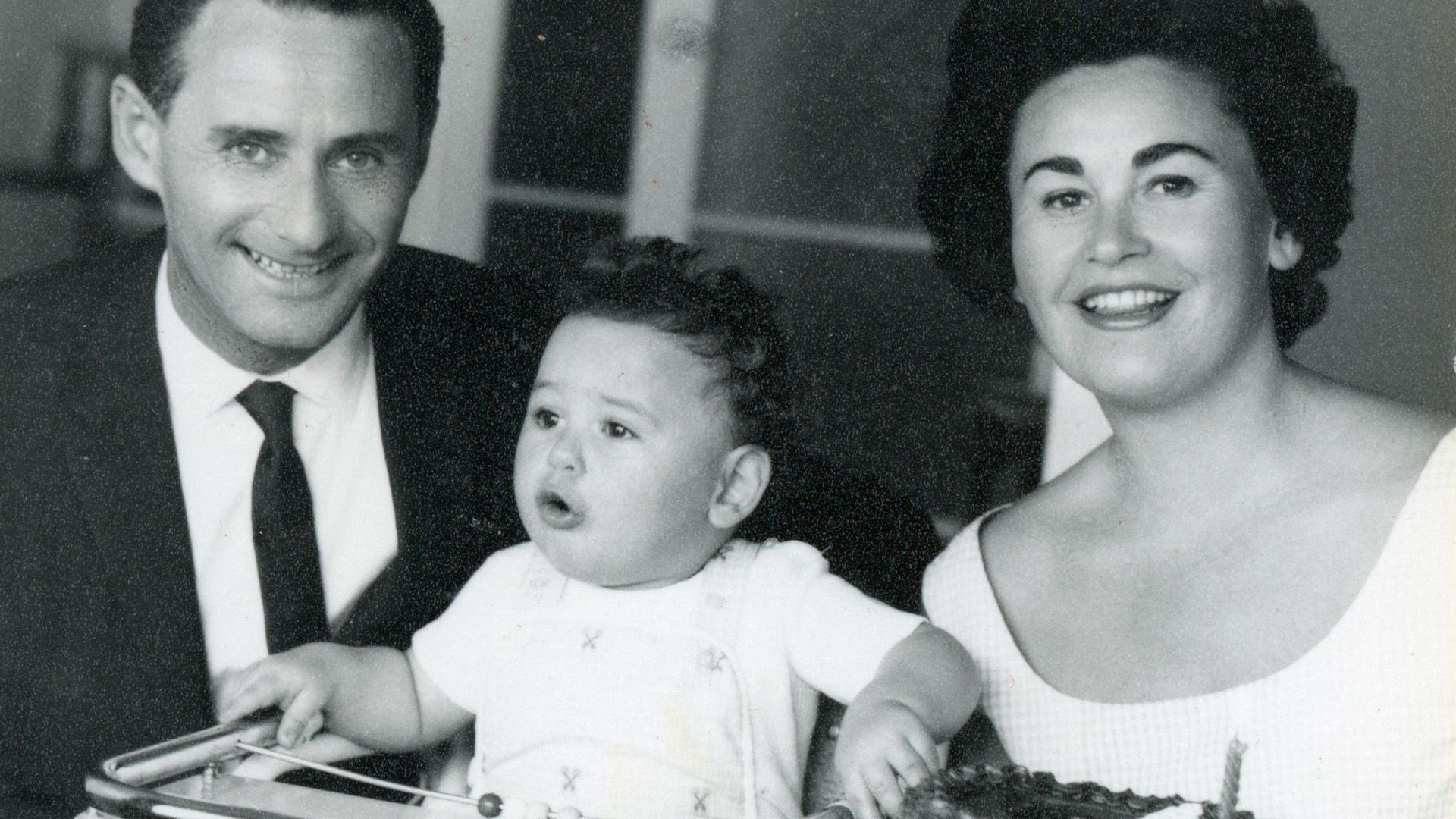

An early destination for Gary—the small town of Krompachy in Slovakia. It’s where Lali grew up, and Gary gets to understand a little about what his childhood must have been like, visiting his school and examining pictures of the kids who attended. As Gary begins to trace the journey from Lali’s hometown to the horrific concentration camp site, it’s with a new awareness. As we learn, he’s never seen a photo of his dad before the war until this moment.

Lali and Gita had wanted to get as far away from Europe after their liberation as they possibly could, which is how they ended up living in Australia. Although his wife visited Europe a number of times, Lali Sokolov never returned, leaving the innocence of his past quarantined in the same continent as the horror he wanted to put behind him. It’s as if the Nazis had reached back in time—not only were they inflicting unspeakable atrocities upon everyday people in their present, they were separating them from their past lives.

Erasure was the point—remembrance and sharing stories is how we can continue to combat this evil. That’s one of the many things that makes Gary’s journey so special to join him on. 80 years on from the camp’s liberation, the passing of time (and of Auschwitz’s survivors) makes it increasingly hard to comprehend the reality of what took place there.

At this one location alone, 1,100,000 people were murdered. One million Jews. One hundred thousand Poles, Roma and Sinti, Soviets and other groups. It’s nearly impossible to fathom the scale—personal accounts are vital to keeping the memory of these people and what they were subjected to alive. With his parents both deceased, it falls to Gary to understand more about their experiences, and in turn share this with future generations.

Gary’s journey of discovery is interspersed with archival interview footage with both Lali and Gita Sokolov. Their son also spends time with the actors who played young versions of his parents during their time in Auschwitz (Jonah Hauer-King and Anna Próchniak), author Heather Morris, Holocaust trauma psychiatrist George Halasz and the 100-year-old Holocaust and Auschwitz survivor Abram Goldberg.

But nothing can prepare him for what lies at his ultimate destination—Auschwitz itself. If anything, walking in has a different sense of reality for Gary, because he knows so much now. “I can’t stop my legs from shaking,” Gary says as he approaches the infamous gate with its three word lie “Arbeit macht frei” that’s seared onto humanity’s memory.

“I’m not ready to walk in yet, sorry” he admits while still summoning the strength to enter. Inside the preserved camp, the horror is confronting, all the more impactful through picturing his parents’ experience there.

There’d be something voyeuristic about joining Gary as he discovers what’s inside if it didn’t have such a transformative effect on him. We know of the piles of shoes and suitcases, the fences, the buildings, the rail lines—and the gas chambers and crematoria (visiting the first of which brings Gary to tears). But this means so much more to Gary than a historical horror. It’s moving to watch him as he moves through the first camp and through Auschwitz II-Birkenau, where extermination became the Nazis’ goal.

“Walking in my parents footsteps is very special,” he tells us, showing just how important a familial connection to the past is. And when he shares of feeling less “empty” upon returning home, we get a glimpse of just how the horrors should never be forgotten—and also how honouring those who lived and died is more than a duty, it can still help us heal and grow some 80 years on from the infliction of trauma.