The twisted genius and razor sharp social commentary of Child’s Play

The murderous toy doll Chucky is back, and more political than ever. The villain has been modernised for a ferociously smart, interesting and forward-thinking film that provides a model for what remakes should be, says Luke Buckmaster.

Ordinarily the idea of a film director remaking Hitchcock would appeal to my cinematic tastes the way a glass of vinegar chased by a shot of battery acid appeals to my wine palette. But I came out of the the ferociously imaginative Child’s Play excited by the prospect that The Birds could be remade – with drones as the flying things that swoop from the sky and attack hapless humans. That change would shift the story’s emphasis away from nature as an enigmatic force targeting us for mysterious reasons, and onto humans as the architects of our own demise, unable to control self-created forces of utter devastation (a particularly salient message in the era of climate crisis).

The same kind of shift is echoed in Tyler Burton Smith’s script for his remake of the schlocky 1988 horror film, which spawned a franchise of outré midnight movies. My memories of them are foggy, having seen several while half-baked during my university years, which I assume is a cineaste rite of passage. I do recall that in the original the villain, Chucky, is a murderous doll possessed by the spirit of a serial killer, who, when cornered by the cops, does what any quick-thinking thug would do and uses a voodoo spell to transfer his soul into the cherub-faced toy.

In the new one Smith transforms Chucky into a robot compatible with a wide range of smart devices, which he can summon and deploy in the manner of the Wicked Witch and her flying monkeys. Thus that hokey voodoo stuff is swapped out for real-world technology. With this comes the exciting potential for sharp-fanged social commentary, which Norweigan director Lars Klevberg rather manically embraces.

Sign up for Flicks updates

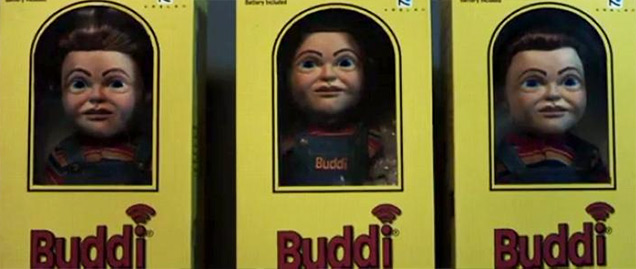

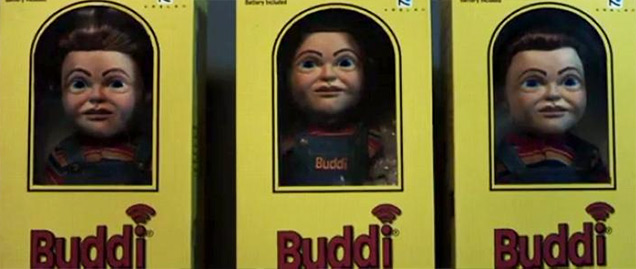

The original Child’s Play attacked and satirized Reagan-era consumerism in America. The remake extends the satire for a world further down the track of neoliberalism and corporate malfeasance. The opening scene is an advertisement for the brand of toys Chucky (now voiced by Mark Hamill) belongs to, called Buddi. This scene coyly doubles as a way of explaining the villain’s key features and abilities. Klevberg then whisks us over to a Vietnamese sweatshop, where an overworked employee, humiliated by his superior, performs one final act of protest – against his boss, the company, society, an unjust world – before throwing himself off the building.

This poor but vengeful sod removes the safety restrictions from one of the assembly line’s highly intelligent robo-toys, creating Chucky, who ends up in the hands of the protagonist Andy (Gabriel Bateman). Chucky gets possessive of Andy, with whom he shares a complicated relationship. Various gruesome deaths follow.

The film is smart, playful and visually interesting, with an entertaining ability to conjure unexpected thought bubbles. In one scene for instance, we catch a glimpse of another young boy’s relationship with his Buddi, which is also problematic but for different reasons. The kid instructs his toy to “salute your master!” and the robot dutifully obeys; it is a weird moment of despotism and cruelty, right out of the George Romero playbook. Like the final scene in Romero’s original Night of the Living Dead, the audience feel, if not sympathy for the monster, then definitely a moral queasiness about the appropriateness of human behaviour towards them.

The idea that tech doodads operating on compatible frequencies might be pulled together and tapped into by someone or something, in pursuit of nefarious purposes, is not just a plausible premise but arguably, in fact, already a reality – depending on a few considerations including how one defines “nefarious.” Companies such as Facebook and Google might not yet have, say, seized control of a person’s smart toothbrush then used it to gauge their eyes out, which is the sort of scene that you should expect from Child’s Play. But just as scholars have long ruminated about the power of poetic truth to transcend factual statements, so too is the horror genre capable of exploring social issues with a unique kind of truthfulness – in the case of Klevberg’s socially conscientious horror pic, the ‘balls to the wall’ kind, tapping into collective fears and inhibitions.

In one scene Chucky commands a self-driving car, reflecting a current unease about what lies ahead when humans give up their place behind the wheel (in case you were wondering: things don’t go well for the passenger). This film has a lot on its mind; a lot to mull over. If Hollywood insists on continuing to harvest crops of remakes, and of course it will, Child’s Play is an example of what should be a modus operandi: that remakes ought to provide a means of exploring contemporary mood and sensibility, reinvigorating old texts with modern attitudes.

That is why a rebooted version of The Birds is an appealing proposition. The rejigged message would be that it’s not the natural things in the sky we need to worry about, but all the other crap we put there. This idea came to my mind during a scene when Chucky commands, flying monkey style, a small number of drones inside a store called Zed Mart. But the moment is brief and begs to be extrapolated. So Lars Klevberg, if you’re reading this, take heed, as I may never say these words again, and nor is any other critic like to: please, please remake Hitchcock.

More

See All