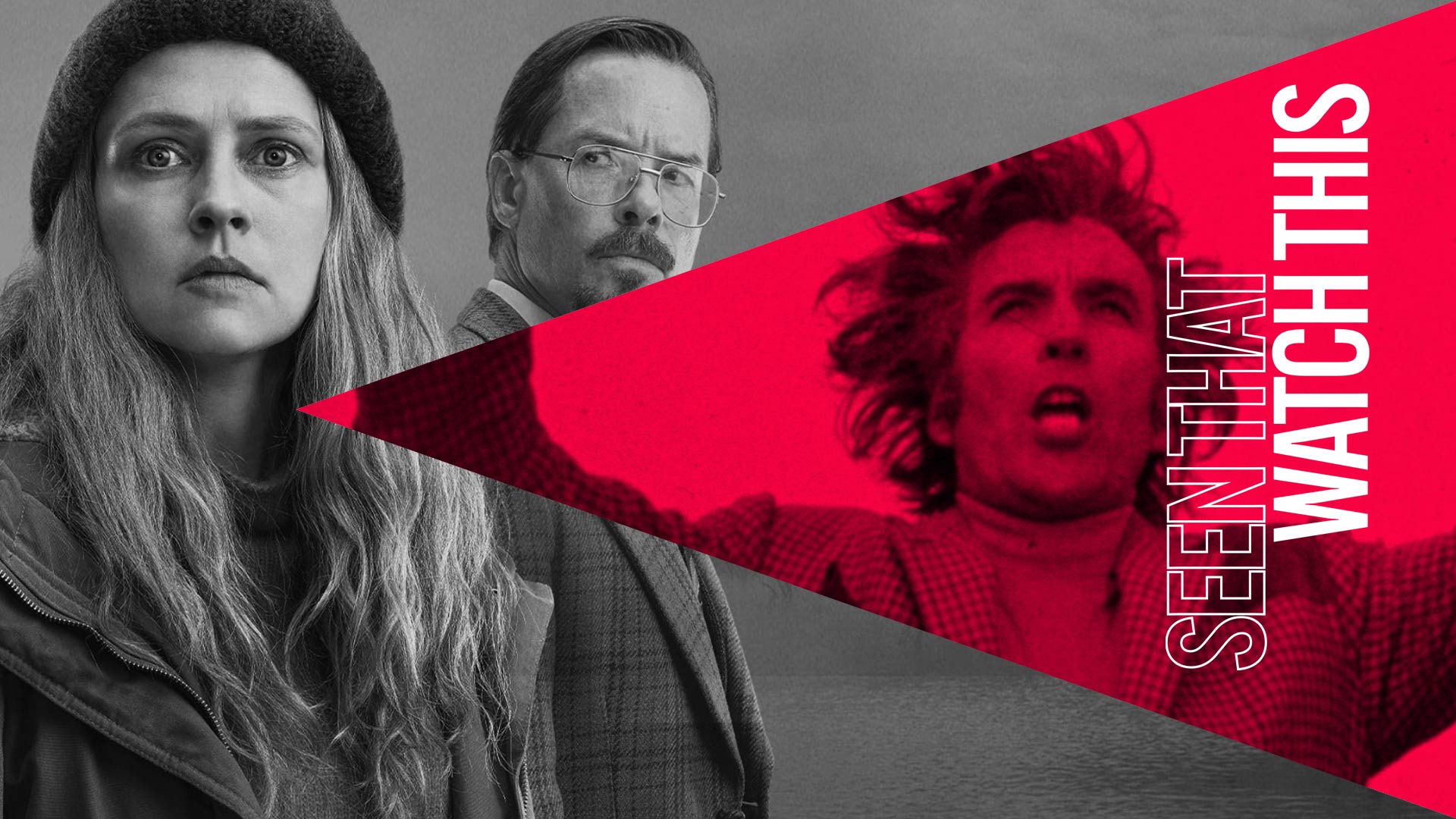

Three great movies about cults to watch after The Clearing

Seen That? Watch This is a column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, inspired by The Clearing, he revisits three of the best movies ever made about cults.

In Disney+’s Australian series The Clearing, Miranda Otto plays a charismatic woman named Adrienne, who dresses fancy and speaks in a slow, pretentious lilt. She’s just your average holier-than-thou churchgoer who likes a bit of yoga, believes herself to be Jesus Christ reincarnated, and runs a cult raising children to be “pure and untainted…away from the suffocating rules of society.” Which turns out to be another way of saying: she deprives them of food, doses them with LSD, and dresses these poor young things in identical clothes, with matching bleached-blonde hair.

This story was inspired by a real-life cult, The Family, and Adrienne by its leader Anne Hamilton-Byrne. The series is well-produced, with a moody wettish aesthetic that screams “cinematic” and includes the requisite shots of rural locations i.e. mist-covered lakes. It’s the kind of shot in which the day always feels a little like night, darkness and shadowy things encroaching at all hours. Narratively, however, The Clearing lacks oomph and struggles to identify an interesting hook with which to frame the drama. It partly gets there by integrating the story of a survivor of the cult, played by a high-impact Teresa Palmer, but doesn’t entrust her with protagonist status and dipsy-doodles in its structure.

For those who found it intriguing but a little wanting, as I did, here are three great films about cults that’ll give you a fuller, more satisfying experience. Trust me, everybody, for I am the reincarnated god of the whatchamacallit, lord of the thingymajigger, dojo of the dojigger. Anyway, here they are.

The Wicker Man (1973)

Still one of the greatest, strangest, wildest films about cults. I might’ve described Robin Hardy’s classic as “inimitable,” if director Neil LaBute and a bee-accosted Nicolas Cage hadn’t indeed imitated it in their 2006 remake, transforming a brilliantly eerie production into daft entertainment. In the original, Edward Woodward’s Sgt. Neil Howie arrives on a remote island, situated off the west coast of the Scottish mainland, to investigate the reported disappearance of a local girl.

It doesn’t take long for him to determine that something is a bit off about the singing, dancing, drinking yokels who live there, with their weird rituals, pagan beliefs and dislike of the word “death.” But what are they playing at? Music theoretically incongruent with the mood and setting (often light, fluffy, uplifting) only makes the atmosphere eerier. Hardy sustains tension exceptionally well, hitting the last act at about the one hour mark. Then things accelerate spectacularly—all the way to a brilliant (and very famous) twist finale.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Roman Polanski’s dread-dripping masterpiece opens with Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and her actor husband Guy (John Cassavetes) arriving at an upscale New York apartment building, where much of the film is based. Rosemary is happy, wide-eyed and optimistic, literally twirling at the thought of moving in. Suffice to say, the dream becomes a nightmare and over the next couple of hours her smile is replaced with angst and terror. Early in the runtime a friend tells her the building “has a high incident of unpleasant happenings” and boy, is he on the money.

Rosemary suspects something is off with her elderly neighbours: a rather understandable response to hearing strange chanting through the walls. Pregnancy is very difficult for every woman, but for Rosemary it’s unbearable and unimaginable pain. Is something wrong with her baby? One of Polanski’s three great apartment movies (the others are Repulsion and The Tenant), Rosemary’s Baby is a paranoia-scented slow burn, with a horrifically iconic ending. My favourite line: “He’s got his father’s eyes.”

Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011)

Martha Marcy May Marlene

Being in a cult is one thing; surviving a cult is another. Writer/director Sean Durkin’s gripping 2011 film Martha Marcy May Marlene oscillates between two timelines: one with Elizabeth Olsen’s titular character in the thick of cultishness, and the other after she’s escaped and is attempting to readjust to society. The latter thread, which follows Martha as she stays with her estranged older sister Lucy (Sarah Paulson), provides the scope to examine the psychological consequences of her involvement in said cult—in particular her long-lasting trauma.

This difficult terrain is made accessible by Durkin’s sensitively drawn writing and direction and Olsen’s wisely layered performance. She has this curiously vacant way of looking ahead—semi-detached from the moment, hauntingly absentminded. We care for her; we want the best for her. For those thinking “yeah yeah, what about the cult?” there’s plenty of that, with John Hawkes as a creepily charismatic leader whose gentle demeanour and skills on the gee-tar mask his wickedness.