Tom Hardy finishes the Venom movies on an insane high

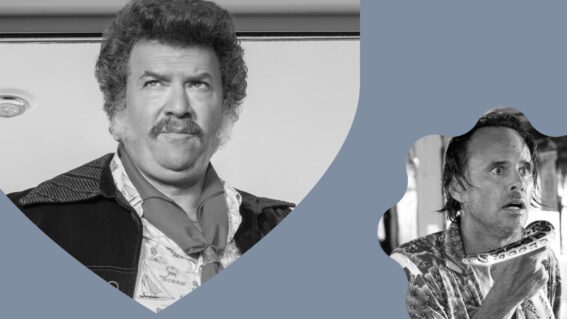

In the Venom movies, Tom Hardy achieved the seemingly impossible: making a CGI-slathered performance feel fundamentally his, writes Luke Buckmaster.

There was a point, somewhere between the first and second Venom movies, when the producers realised how silly the whole thing was and decided to turn the franchise into a black comedy. Thank god they did: while I didn’t care for the first film I dug the Andy Serkis-directed second: a silly, wily sequel sprinkled with outré moments that made me giggle. In one the titular symbiote, having decided to leave the body of Tom Hardy’s former journalist, Eddie, and slither away on his own, visits a nightclub and delivers a speech to a gakked crowd, deploring his human host and calling for an end to alien-directed hostilities.

“Eddie was wrong! He kept me hidden, because he was ashamed!” Venom, draped in glow in the dark silicone, bellows on stage. I compared this scene to Bad Boy Bubby—the animalistic eccentric lapping up attention from an audience he appreciates but will never understand, and vice versa. Here Hardy is verbally present, vocally portraying Venom in the style of (his words) a “James Brown lounge lizard,” but he doesn’t appear on screen, removing the franchise’s central appeal: a berserk Jekyll and Hyde routine. Eddie deals not just with the alien voice inside his head but its ability to take over or protrude from his body.

As for the second and reportedly final sequel, Venom: The Last Dance, I didn’t care for this film whenever Hardy wasn’t in it; thankfully he’s in it a lot. After a darkly lit prologue featuring a cranky villain from a far-flung otherworld, grumbling about being imprisoned for eternity, writer/director Kelly Marcel plunges into a bar in Mexico and returns the aforementioned routine. Eddie is happy with water but Venom wants a strawberry margarita; the bartender watches in horror as the symbiote (a liquid-like life form that survives by bonding with a host) wins the argument and serves up a drink.

This moment might be simple on paper, but requires some shrewd comedy from Hardy. Conceptually it’s similar to Beetlejuice‘s famous Banana Boat scene, in which a bunch of characters were forced to dance and mime by ghosts, the actors directed to project the bemusement, rather than horror, of limbs moving independently of their brains. But by this point in the Venom franchise Eddie is well accustomed to being maneuvered by an impetuous puppeteer, accepting the loss of an autonomous self with a resigned look on his face, more exasperated than bothered. This is difficult to portray, but Hardy makes it look easy.

Marcel (one of the writers of the previous two installments) trusts the actor to carry the scene, or at least his part of it; there’s of course fandangled CGI assistance. This moment, like many others, merges the physical and the fake, the real and unreal, Hardy’s actual voice and his monstrously cartoonish one, the actor in a tussle or dance between his own body and its virtual extensions. Being able to make this spectacularly altered, inherently schismatic character still feel fundamentally his is quite the achievement. Holding your own in an Oscar-baiting period drama is much easier than subverting a comic book blockbuster.

The Venom franchise retrospectively highlights the biggest mistake committed by the Ghost Rider movies, of which there were two—released in 2007 and 2011 respectively—starring Nicolas Cage as Evil Knievel-esque protagonist Johnny Blaze. After making a deal with a demon he’s transformed into a “spirit of vengeance” whose skeletal body is literally on fire, his face a flaming skull. It wasn’t a fair deal for Blaze, or for the audience, the fabulously eccentric Cage disappearing whenever the protagonist transforms, replaced by CGI and a stunt double. The producers didn’t realise their greatest special effect was a human.

While The Last Dance, like the other two movies, leans too heavily into CGI-slathered hokum, at least it puts Hardy at the centre of the spectacle. When Eddie/Venom arrive in Las Vegas in the film’s second half, heading for the slot machines, I realised I could’ve happily watched a whole hour of them stumbling up and down the strip, channeling the ghost of Hunter S. Thompson, no need for recreational drugs to fuel the fear and loathing, given the symbiote beast’s ability to conjure a nightmarish trip any time, anywhere.

But Marcel does that very comic book movie thing, transitioning to a giant showdown and a paroxysm of special effects. These movies are cinema’s amusement park rides, maximizing sensory overload and minimizing human performance. It’s very hard for a leading actor to bring any kind of ingenuity or experimentation, which makes Hardy’s performance a rare treat and a career highlight.