Two-parters are back for round two – and the same fate as last time?

Hollywood clearly has a short-term memory problem. Rory Doherty looks at how studios revived the dormant trend of the two-parter – and the risks that come with it.

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One

If you went to see Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse in the past month (and looking at the numbers, a few of you did), you may have spent the last 20 minutes wondering how they were going to wrap up a story that, so far, had focused on setups and introductions. Miles Morales’ multiversal adventure was dazzling, entrancing, and according to some animator whistleblowers, utterly exhausting, but for those unfamiliar with the studio’s franchise plans, it also felt suspiciously like the first half of a story. Many were surprised, even frustrated, when the film ended on a cliffhanging ‘TO BE CONTINUED’, with Beyond the Spider-Verse to wrap up Miles’ story next March.

This year, we’re treated to another double whammy of two-parters, with Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One followed by the next chapter in Denis Villeneuve’s desert epic with Dune: Part Two. Like Across the Spider-Verse, some fans were unaware they had bought a ticket to 50% of Dune in 2021, with the subtitle Part One appearing on-screen but not on any marketing materials. When Spider-Verse and Dead Reckoning conclude next year, they’ll be followed by the Broadway smash hit Wicked kicking off its own two-part adaptation, with the first film ending at the play’s interval. But will studio confidence that audiences will keep turning up for fragmented stories have faltered by then?

Two-parters are nothing new in cinema; producing two connected films back-to-back to save costs is a tradition that dates back internationally to the 30s. (Alexander Salkind was a modern pioneer of the trend, producing two Three Musketeers films and the Richard Donner Superman films both back-to-back in the 70s.) But less common is breaking one elongated story into multiple parts, as studios are cautious about anticipating lasting audience investment in a series. Before Fellowship of the Ring dropped in 2001, Hollywood was convinced the legendary Lord of the Rings production would go down as a costly disaster.

Even the LOTR, Matrix, and Back to the Future trilogies have relatively distinct stories in each film, and by the time Harry Potter closed with Deathly Hallows Part 1 and 2, some audiences had started grumbling that they were only getting half a story, or that the first half was filled with only the boring bits. But that duology was a huge hit, so every in-progress young adult franchise split their finales into two parts. Sure, The Hobbit trilogy came out at this point, but with the success of LOTR behind them, a prequel trilogy was a no-brainer. (Seeing how they came out, maybe it shouldn’t have been…)

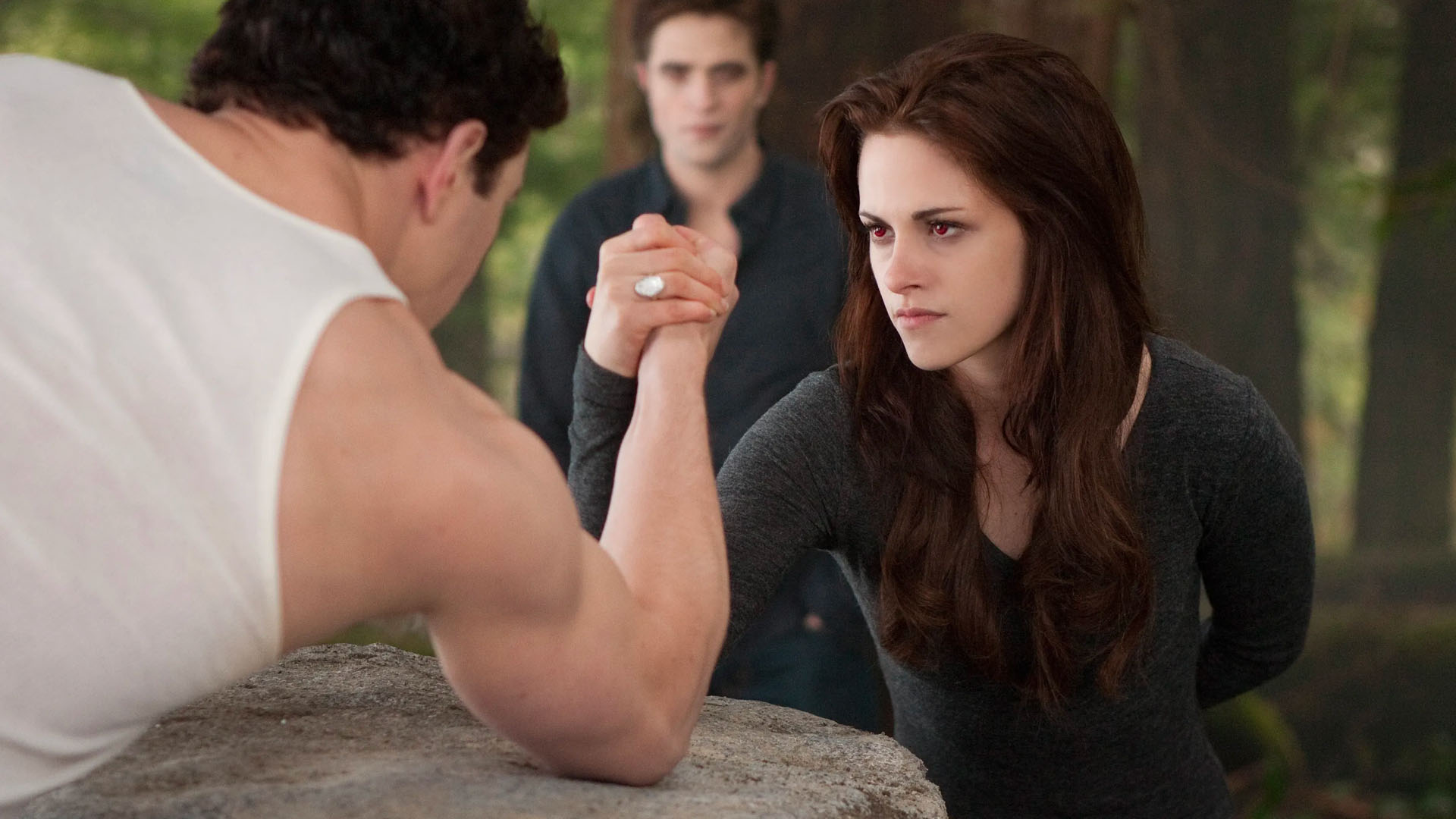

The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn films were financial hits, but the disappointing box office of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 hit the brakes on bankrolling any future oversized productions, meaning The Divergent Series never actually greenlit its final instalment. That’s right, the series ends on a cliffhanger and has never been resolved.

After the YA debacle, two-parters died down… before being revamped two years later with Stephen King’s horror epic IT, with the first film telling the portion of the novel set in the past. It was followed up with the MCU concluding their “Infinity Saga” with Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame. Those superhero blockbusters ended up as two of the highest grossing movies of all time and wrapped up in 2019, so you can trace pretty directly from there why two-to-three years later, we’re inundated with new two-parters. (The outliers in this trend? Dune and IT, which didn’t film their sequels back-to-back and had to wait until opening weekend to see if they’d be able to finish their story.)

Films are not TV shows, and audiences will inevitably grow tired of the big-screen experience being increasingly serialised. The success stories of the recent two-parter trend will inevitably be the films that tell a succinct, self-contained story that doesn’t shortchange audiences who still need to be fully coaxed back into the rhythm of regular cinema visits post-pandemic.

Still, two-parters could be welcomed in today’s franchise-focused climate; Marvel’s Phase Five opener Ant-Man and The Wasp: Quantumania was basically an open-ended promise that somewhere in the future good storytelling would happen, and it was swiftly rejected by critics and audiences ready to hop off the MCU train. Maybe the guarantee that there’s only one more chapter is a sign of refreshing restraint?

Hollywood clearly has a short-term memory problem, more likely to jump on bandwagons than take risks on innovative storytelling, so it’s maybe no surprise at how quickly they revived a dormant trend. But having to wait the best part of a year to see a complete story (Matrix and Deathly Hallows took only a six month break) is unlikely to always build up anticipation, it might kill off interest. We should pay attention to see when studios learn this lesson for the second time in ten years.