United against injustice: devastating doco No Other Land’s filmmakers speak

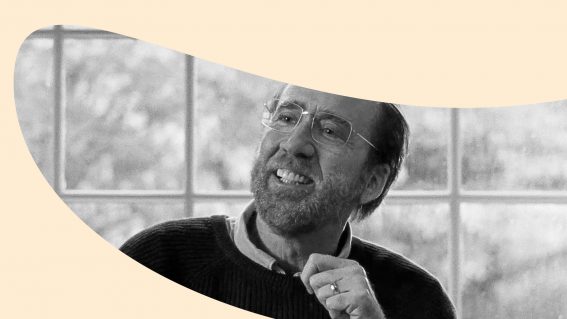

Award-winning documentary No Other Land depicts the destruction of Palestinian villages by Israel and the grim realities of life under illegal, armed occupation. Palestinian filmmaker Basel Adra and Israeli co-director Yuval Abraham discuss their essential, unforgettable film with Stephen A Russell.

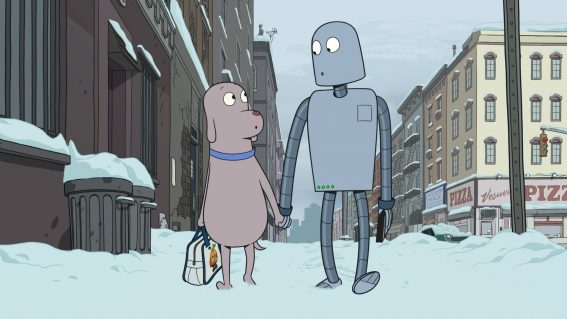

No Other Land

Alongside the severing of water pipes and wells filled in with cement, watching the Israeli army (IDF) destroy a school hand-built by the illegally occupied West Bank community of Masafer Yatta is the most distressing image in shattering documentary No Other Land. Combined, these inhuman acts are designed to erase the future.

“People must understand that this is unnormal, that this is insane and they should be against it,” Palestinian co-director Basel Adra says.

He was born in 1996. Masafer Yatta was declared a training zone by the IDF in 1980, with the locals forced to battle this unjust proclamation and resulting demolitions in the occupying force’s courts.

“It’s exhausting,” Adra says of this harsh reality. “You are born and raised, growing up living our entire life under the occupation, suffering every day.”

As hopeless as the cause can sometimes seem, there was no question of him following his staunch father’s tireless fight for justice. “When you live in this situation, you either choose to be silent or pay a price,” Adra says. “My father chose not to be silent. I am proud that they raised me this way.

“It’s the main reason I became an activist, filmmaker and journalist, because I wanted to take the stories from Masafer Yatta to the world.”

Shared values

Adra worked alongside fellow Palestinian filmmaker Hamdan Ballal and resolute Israeli colleagues Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor to get Masafer Yatta’s message out.

No Other Land, the unforgettable result, debuted at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) in February, winning the Documentary Award and audience prize, the first of many to follow. I speak to Adra and Abraham shortly after their return from representing No Other Land at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam.

“We are good friends and care about one another,” Abraham says of Adra. “We share the same values. What we want for the future of our two people is that we have equal rights. But that struggle is happening against a backdrop of total brutality, destroying schools and filling up water wells with cement. It’s the complete opposite of empathy.”

When Abraham called for a ceasefire, the release of all hostages and for Israelis and Palestinians to be treated equally while accepting the trophy alongside Adra at Berlinale’s closing gala, he was perversely accused of antisemitism.

“It was scary,” Abraham recalls of the aftermath. “A right-wing mob came to my mother’s house [in Jerusalem] and she had to leave for a few days.”

While he feared for his family, Abraham notes that the absurd response—not unlike that faced by also-Jewish The Zone of Interest director Jonathan Glazer after his Oscar acceptance speech—ironically boosted the film’s profile.

“While it was very difficult, unfortunately, sometimes it takes a backlash for people to hear about it,” Abraham says. “From the very beginning, it was how do we get people to hear about Masafer Yatta?”

When the pair first began documenting IDF home demolitions in the West Bank, they reached a few hundred folks through social media. “Now there are millions listening and seeing the community’s story,” Abraham says.

Eyes opened

The men first met when Abraham joined Szor to cover the demolition story. “I was interested in writing about house demolitions in Hebrew because I felt it was under-reported in the Israeli media and it was seen as some kind of legal dispute where you have people building illegally and the state enforcing the law,” Abraham says.

He was about to interview Basel when the latter got the call that a demolition was in progress. “So he had to run to film it, and I ran after him,” Abraham recalls.

“It was a very shocking experience, because I’d read about this happening, but it’s always different, emotionally, to witness something with your own eyes. It becomes very clear that this is a political act of displacement.”

The image of a sheep herder whose shelter was levelled has stuck with Abraham. “He was sitting down in the sun afterwards, with all of his sheep around him with no place to be. He seemed so exhausted, and I really felt the injustice at that moment.”

He hopes the film can encourage more Israelis to open their eyes, however difficult that may be. “A lot of people want to remain in this place where they don’t know,” Abraham says. “When you confront them with aspects of their life that make them feel uncomfortable, guilty or contradict their worldview, often the response is to attack you. To de-legitimise you as a way to disregard what you’re saying.”

Abraham has lost friends and family members, but it’s a price worth paying. “There is a strong community of Israelis who are like me, and while we are not many in number, we are very much connected to one another,” he says. “There’s a strong sense of community who oppose the occupation and understand that our future is directly linked to the freedom and security of Palestinians.”

Drive for justice

Different coloured registration plates on cars—yellow or green—are a simple but profoundly disturbing reflection of the unjust division highlighted by No Other Land.

The film stays in Masafer Yatta, from Basel’s perspective. “So you see my car leaving, but the camera doesn’t leave with me,” Abraham, who lives in Jerusalem an hour’s drive away, says. “That’s our attempt to mirror the boundaries controlling Basel’s life, as a Palestinian who cannot leave with me because he will be stopped at the checkpoint.”

Every time he leaves, Abraham keenly feels that injustice. “It’s something that I am ashamed of,” he says. “But for me, that guilt is not paralysing. I didn’t choose where I was born, but I can choose how to act in a way that best reflects my commitment to human rights and my belief that we are fundamentally equal.”

Pointing to northern Gaza, Abraham notes that the UN has warned the population is at risk of starvation. “They don’t have time to wait for change, which is why we urgently need, at this moment, some kind of international intervention and sanctions.”

Whether that will happen is another question. Adra is unconvinced that arrest warrants issued by the International Criminal Court for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his dismissed defence minister Yoav Gallant will be actioned.

“Western governments, who all the time call themselves the ones who are protecting international law, ignore it, especially the US who use their veto against recognising the Palestinian state or a ceasefire in Gaza,” Adra says. “There should be sanctions. It’s the turn of those governments to show up and to stand for this resolution.”

No Other Land will not be ignored. “The movie is our resistance,” Adra adds. “Despite all the darkness, especially with what’s going on in Gaza, I have hope that millions of people around the world will watch this movie and take action.”