What it’s like to rewatch 12 Monkeys during an actual pandemic

The 25th anniversary of Terry Gilliam’s time travelling classic, about a world struck by a deadly virus, arrives during a year marked by a real-life pandemic. Critic Luke Buckmaster revisits the film in this context, and also explores what it says about climate change.

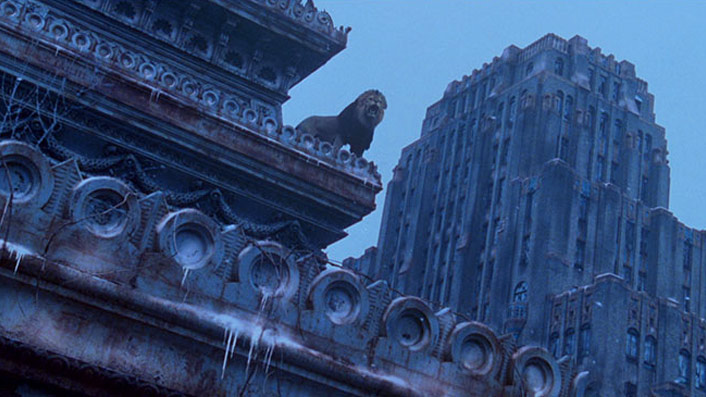

What’s watching 12 Monkeys like during a real-life pandemic? Terry Giliam’s 1995 time-travelling sci-fi is based, after all, in a world which has, or will have, or did have—depending on vantage points in the space/time continuum—a virus that wipes out a huge portion of the global population. More than COVID19: the death toll is some five billion people, and there are global warming-esque effects to boot: Philadelphia for instance gets covered in ice due to extreme changes in the climate. Humans are plagued good and proper but nature is coming back, lions and bears roaming the once-filled streets.

See also

* All new movies in cinemas

* All new streaming movies & series

The person—James Cole (Bruce Willis)—assigned the not insignificant task of whizzing back in time and saving the world is a violent thug and a prisoner. This probably should have raised some red flags, but the choice of candidate to rescue humanity from the brink of oblivion turns out to be far from the biggest mistake committed by the bureaucrats of the future. For starters they accidentally send Cole back to 1990, not 1996—the year the virus outbreak begins. Additionally (yes: there will be spoilers) they actually get the cause of the plague—the reason so much of humanity gets wiped out—completely wrong.

The bureaucrats believe our brush with extinction came about/will come about/is coming about due to the nefarious actions of a group called the Army of the 12 Monkeys. Yet Cole discovers these people, led by a bug-eyed Brad Pitt as the manic anti-corporatist Jeffrey Goines (a warm up act for Tyler Durden) are just a bunch of beatnik activists whose biggest crime is, was and will be freeing animals from the zoo.

Everything is in decay

That’s one pretty epic intelligence bungle. It remains more than plausible however given a) the real world—particularly America in recent years—hasn’t exactly been a source of inspiration when it comes to quality leadership. And b) everything in the future is in a state of decay, which is manifest in the characteristically Gilliam-esque junkyard settings (his films have such terrific lived-in qualities) but also applies to the very concept of knowledge.

What I found particularly compelling about rewatching the film from the perspective of somebody who lives in Melbourne—which has recently emerged from one of the world’s longest lockdowns, during which we practically eliminated coronavirus—is the psychological stickiness, the unease, the strange vibes baked into virtually every aspect of the experience. Gilliam films famously deploy hallucinogenic visions to explore matters of the mind (see also: Brazil, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, The Fisher King, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus) but 12 Monkeys relies more than most of his other work on a continual, unusual energy rather than individual scenes or images.

During the pandemic I have sometimes stopped and wondered: to what extent is everybody else feeling what I’m feeling? Or as Joaquin Phoenix put it in Joker: “Is it just me, or is it getting crazier out there?”

There is dread everywhere

Those sorts of questions mix up subjective and objective reality—even more than usual—when we sense, when we know, when we can see and feel something huge and unusual happening around us, turning even everyday sights into surreal visions. Walking down the street during a pandemic is not the same as walking down the street before one. Pushing aside the obvious visual indicators (i.e. people wearing marks) there are differences, some intangible, that change the energy and life on the street. But again the question beckons: how much is objectively there and how much is in our minds?

In 12 Monkeys a difficult-to-define sense of dread clouds the air, the frame, the timeline, even the characters’ impressions of themselves and each other. When Cole lands in 1990 he is thrown into a mental institution, where he is visited by Dr Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe). Our protagonist is not exactly in tip-top physical and mental shape: shackled and chained, rocking back and forth, drooling from the mouth, blood smeared on his body, gnashes and bruises on his head, he is talking about how the air is fresh—no germs!—and how he needs to go, needs to go, must go and gather information, because aren’t you listening he’s from the future…

After a while Cole entertains the thoroughly rational idea that he may indeed be crazy; that his experiences in the year 2035 (the date he is sent back from) were visions in his head. He is forced to scrap this line of thinking when he accurately predicts developments that haven’t happened yet.

Complicating Cole’s mindset is a recurring dream in which he is a boy who sees himself, as an adult, shot dead while wearing a disguise (the old fake mustache caper!) which turns out to be a memory, as we discover in one of the film’s final scenes. Cole’s temporal displacement and psychological confusion feeds into a message you don’t often get in films about the end of days, or end of days-ish scenarios: that every half-decent apocalypse is not just planetary but personal.

When there is still time, there is hope

On the subject of hope during apocalyptic times, Gilliam puts forward an interesting and grimly optimistic message. Rejecting the hackneyed view that one person has the power to save the universe—which is popular in superhero movies and described as “the guiding myth of neoliberalism” in this excellent essay on Salon—screenwriters David and Janet Peoples make it clear the future is rooted one way or the other.

“This already happened. I can’t save you. Nobody can,” Cole says at one point, hammering home that this is not one of those time travel movies in which consequences of the past can be conveniently reversed to save the future—a book or significant object to procure over here; a showdown with Biff Tannem over there.

But when there’s still time (even if, in this instance, time runs backwards) there is still hope. Not to entirely ‘solve’ things but to improve them; to save and salvage what’s left; to fight for a better future. Immediately after dropping the aforementioned line, Cole adds: “I am simply trying to gather information to help the people in the present trace the path of the virus.” In other words: we can’t wave a wand and get rid of this thing, time travel or no time travel, but we can learn, study, improve, work hard to make things better. The future is going to be difficult, but all hope is not lost.

Who is the true lunatic?

That message is particularly salient message in the era of the climate crisis. Prior to rewatching the film, which I hadn’t seen for years, I had completely forgotten the following words spoken to Railly by Dr. Peters (David Morse), a virologist who is ultimately responsible for the spread of the deadly virus and delivers this great little speech:

“I think, Dr. Railly, you have given your ‘alarmists’ a bad name. Surely there is very real and very convincing data that the planet cannot survive the excesses of the human race: proliferation of atomic devices, uncontrolled breeding habits, the rape of the environment, the pollution of land, sea, and air. In this context, isn’t it obvious that Chicken Little represents the sane vision and that Homo Sapiens’ motto, ‘Let’s go shopping!’ is the cry of the true lunatic?

That last line, about the cry of the true lunatic, reminded me of an article I wrote for The Guardian in September last year, reflecting on an Extinction Rebellion protest during which a large group of activists including myself blocked a bridge to demand action on the climate. I wrote: “What is crazier: dancing on a bridge to build political will for urgent action on climate change, or continuing as if nothing is wrong?”

Beautiful things exist, even in decay

While there is currently renewed hope about the planet’s ecological prospects, drawn from a range of factors including the election of Joe Biden and the growing list of nations committing to net zero emissions, the fact remains that we have a hell of a fight on our hands; nobody can put the genie back in the bottle. In climate activism circles there is a concept called ‘doom and gloom’, involving acknowledging the severity of reality without ignoring that beautiful things exist—even in a state of decay.

We see that concept visualised in Mad Max: Fury Road when the Keeper of the Seeds retrieves what remains of a simple green plant from her satchel, its leaves looking wonderful in this sun-scorched world. And in 12 Monkeys, Cole at different moments is delighted by the taste of the fresh air in the 90s, sticking his head out of a car window and gulping down big mouthfuls of oxygen.

But the hero (of sorts) doesn’t rest on his laurels. He has a job to do: that not insignificant task of saving the world—or more to the point, improving the world. Cole keeps slogging it out, returning ultimately to that moment from his childhood. Despite travelling great geographical and temporal distances, he has come full circle. You must keep fighting for the future, the film appears to be saying, but do so knowing you’ll never stop fighting inside yourself. I admire that message. The apocalypse is personal, the pandemic is personal, the climate crisis is personal; our struggle is ongoing.